Exhibition Shows What America Looks Like From Beirut

Beirut is a 5,000-year-old city, or series of cities, each layered over another on the same site, living with the previous eraÔÇÖs ghosts. Today, it can feel like a place steadily, and in certain ways, heedlessly devouring itself to meet the various needs of an uneasy and unevenly affluent now, the ancient souks rebuilt as a series of covered outdoor shopping malls┬áÔÇö Zaha Hadid designed one┬áÔÇö and Miami-style starchitect-luxe condo towers (by the likes of Herzog & de Meuron and Norman Foster) coexisting side by side with pocked concrete high-rise ruins, legacies of when the city was divided between Christian and Muslim sections during the 1975ÔÇô1990 civil war, and snipers would nest in the upper floors, keeping watch on the borderline between them. ItÔÇÖs a city crowded with Syrian refugees in a nation itself overrun and undergoverned, all within commuting distance to the frontiers of the Islamic State. It has problems with the basics of municipal functionality┬áÔÇö the power supply and garbage collection┬áÔÇö even as developers extend its borders out into landfill in the Mediterranean. And yet, through this, life goes on: It remains a city of beguilingly romantic cosmopolitan complexity and potential.

Last fall, A├»shti by the Sea, a high-gloss luxury mall, was built in an industrial waterfront area of town, a futuristic spaceliner moored between the highway and the sea. It feels a bit like itÔÇÖs at a wary valet-parking remove from the city itself, and solidly within what was the Christian zone during the civil war. It was designed by the British architect David Adjaye, who is better known for his museums than his upscale retail, for Tony Salam├®, a Lebanese retail┬ámagnate who wanted to be better known for his collection of contemporary art. And so there is a museum in this mall, too.┬áBy bringing an outpost of name-brand art to a place which didnÔÇÖt have much ÔÇö even if it is in the same building as a place to buy luxury name brands ÔÇö┬áSalam├® has tried to elevate his own and his cityÔÇÖs position as a outpost for the┬átransnational art┬áelite. Still, its opening last fall ignited a certain amount of knowing┬áeye-rolling┬áin the art press about Salle and Gucci cohabiting.

As Salam├®┬ápoints out to me, there is a separate entrance in the building for the A├»shti Foundation, which occupies four well-proportioned floors at the end of the building, overlooking the waterfront industrial gas tanks next door. In any case, he didnÔÇÖt invent this hybrid real-estate beast: There are art collections in the Iguatemi shopping centers in Brazil, and Shanghai has its K11 Art Mall. Luxury fashion brands and contemporary art are self-advantageously allied these days: DonÔÇÖt forget the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, or the Fondazione Prada in Milan.

Salam├®, who comes from a prominent Beiruti family, has been collecting art in a serious way for a decade, after dabbling in collecting stamps and traditional rugs in his youth. ÔÇ£I bought randomly this art┬áÔÇö I donÔÇÖt want to say bought, that is for the stores. I collected in a way what I liked. I visited many galleries, because I am an impulsive buyer,ÔÇØ he says when we meet up in the the restaurant on the ground floor of A├»shti, which is decorated with a couple of Doug Aitkens and a pair of Richard Prince Instagram paintings, and protected from the sunÔÇÖs glare by a golden scrim over the windows. ÔÇ£I went from one painting to another artist to another.ÔÇØ But when it came time to open the museum he contracted the New MuseumÔÇÖs Massimiliano Gioni, whom heÔÇÖd met when the curator was working on a 2014 exhibition┬áof┬ácontemporary art from and about the Arab world, ┬áto make some sense out of his collection. Salam├® is an agreeable, solicitous manÔÇö an impresario,┬áclearly used to holding court amidst these polished surfaces. He shows me the books which accompanied the opening exhibition, and the new one.┬áÔÇ£I realized when I did the books and saw them that the collection made sense; it is in a way a collection.ÔÇØ

Salam├®ÔÇÖs collection is focused on the West, as if to digest it. In that, heÔÇÖs not unlike a number of collectors in the new global art market, continuing a process of cultural-prestige transfer which harkens back to when American robber barons (see: Henry Clay Frick) bought up the aesthetic trophies of Europe. HeÔÇÖs always liked Pop artists like Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Roy Lichtenstein because, growing up in Lebanon, their references held some talismanic appeal, exalted, mysterious, and familiar all at once. It was a way to mainline the cultural power of the USA, to both read it and in various ways interestingly misread it. (It also faces outward, across the sea to Europe and America, not inward, toward the Lebanese art scene, and for that is criticized locally: One day, wandering down hipsterish Armenia Street, lost trying to find a friendÔÇÖs hotel, I stopped into a shop called Zawal, where the woman there was openly dismissive of the idea of Salam├®ÔÇÖs foundation as being for a disengaged ÔÇ£nouveaux riche.ÔÇØ)

And so appropriately enough A├»shtiÔÇÖs second show ever, which opened last month while I happened to be in Beirut, is titled ÔÇ£Good Dreams, Bad Dreams┬áÔÇö American Mythologies.ÔÇØ Gioni assembled it out of Salam├®ÔÇÖs collection of art about the USA ÔÇö ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt go shopping,ÔÇØ he told me, with his usual knowing half-wink, given that the foundation shares a building with a mall. The invitation (as well as the banner outside of the museum) is a Richard Prince Cowboy┬áÔÇö one of the famous rephotographs the artist took of Marlboro advertisements. At the opening, which looked a bit like a July Fourth corporate picnic on the promenade out back of the seaside mall, they served ÔÇ£American DreamÔÇØ burgers (ÔÇ£hand-pattied with loveÔÇØ), ÔÇ£Pop CultureÔÇØ corn on the cob, ÔÇ£Mythology Merguez DogsÔÇØ and popcorn, out of a cart. Oh, and lots of Budweiser and Jack Daniels.

Salam├® says he grew up sympathetic to the United States, or at least some idea of it gleaned through the movies. He remembers watching the American flag being burned during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979 and thinking ÔÇ£Oh my God, why are they always insulting America? Because maybe we are pro-Western in our country and our school.ÔÇØ During the civil war, Lebanon even lacked for Coca-Cola. ÔÇ£We knew the myth, even before getting to know the real thing,ÔÇØ he says. He finally went to the U.S. when he was 24, in 1991, and stayed for three weeks, visiting New York, L.A. and Dallas.

ÔÇ£So it was this dream, I remember, from watching the movies, I remember 9 1/2 Weeks, or Wall Street┬áÔÇö what was his name, Gordon Gekko, and youÔÇÿd see all the greed, that American lifestyle, was it too much?ÔÇØ he says.

Meanwhile, heÔÇÖd been doing more research on America. ÔÇ£I always liked business, and I bought many books, about Ford, Richard Nixon, DominoÔÇÖs Pizza; I bought TrumpÔÇÖs first book, The Art of the Deal.ÔÇØ He went to Trump Tower first when he arrived in Manhattan (and also Saks Fifth Avenue and Bergdorf Goodman.) ÔÇ£I had this whole idea of Pop art,ÔÇØ around this time, he remembers. ÔÇ£This show was maybe born then.ÔÇØ

Since Pop Art is a transformative riff on American pop culture, then you at least have some of the context no matter where you are in the world, from movies and advertising. ÔÇ£Part of the collection is always related to the business, of fashion, of graphics,ÔÇØ he says.

ÔÇ£Americans are very good marketers,ÔÇØ he says, even to ourselvesÔÇö he remembered, when he first visited, being surprised at how many American flags Americans hang all over America. He┬ágives a nod to the Richard Prince Instagram pictures on the wall, which depict the new technology of self-marketing while being something of an example of that itself.

The A├»shti Foundation is a big bright place to look at art (and certainly more flexible than GioniÔÇÖs home base of the New Museum.) Before Salam├® and I┬áspoke, heÔÇÖd been deep in conversation with one of his art dealers, Massimo De Carlo (Milan/London/Hong Kong), who, along with several other well-regarded gallerists (Stuart Shave, Kathy Grayson, someone from┬áDavid Kordansky, among others) had flown in┬áto attend the opening of ÔÇ£Good Dreams, Bad Dreams.ÔÇØ Many hadnÔÇÖt been to Beirut before and were curious as to where all this work he was collecting had ended up.

HeÔÇÖs known De Carlo since around 2008, around the time when he decided that he wanted to create a foundation. Two years before, heÔÇÖd met the dealer and art advisor Jeffrey Deitch at Art Basel, and was inspired by a man Deitch had worked with for years, the Greek collector Dakis Joannou, as well as the American idea of your-name-here philanthropy: ÔÇ£Everyone has built a museum or has a room in the museum,ÔÇØ with their name on the wall, he says. ÔÇ£This encouraged me also to ┬ámake the museum.ÔÇØ

The title of the show comes from a 1996 installation by Allen Ruppersberg listing off, on a series of hand-painted signs, various books he owns, and its idiosyncratic system captures some of the way that that Salam├®ÔÇÖs voracious collecting seems to work: HeÔÇÖs trying to capture something. ÔÇ£Raymond Pettibon, I always thought he should do every single American icon from Superman to Wonder Woman to the cars to a surfer,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£He just did some of the new works for me as a commission.ÔÇØ

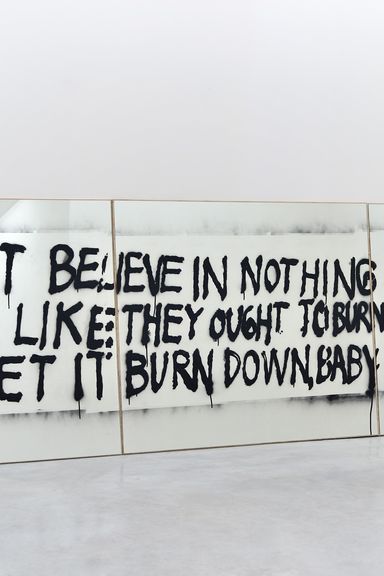

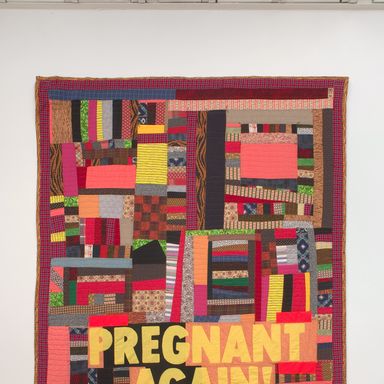

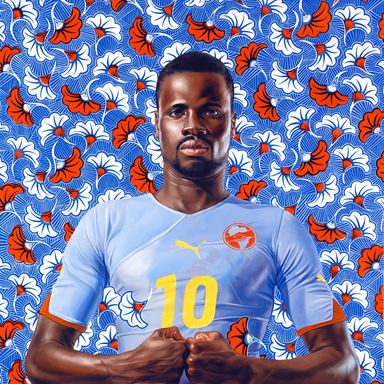

A lot of the work in the show will seem familiar to a New York gallery rat who has seen his share of Longos and Wileys and Uoos and Lowmans and Ligons and Alex Israels and then some. To this hard-to-impress cohort, the show can seem more like a cozy sampler of blue-chip insights or provocations┬áÔÇö artworks which grabbed Salam├® for whatever reason ÔÇö than what seems like, at least to this American, a more rigorously assembled take on America. Still, it has its satisfactions even on those terms┬áÔÇö an enormous 2006 Julian Schnabel of a surfer on a wave, Amanda Ross-HoÔÇÖs Pregnant Again and Again quilt hanging; Duane HansonÔÇÖs droll Man on Mower;┬áRashid JohnsonÔÇÖs BAADASSSSS wall unit; Richard PrinceÔÇÖs 1987 Buick Grand National covered in a vinyl wrap of seductive ladies; Sam DurantÔÇÖs mirror tagged with the words I DonÔÇÖt Believe in Nothing, I Feel Like They Ought to Burn Down the World, Just Let It Burn Down, Baby. Though when you take a step outside of the art-world bubble, what makes it interesting is seeing these works in this particular context, to try to imagine seeing it through a localÔÇÖs eyes, in a city where most of these artists have never been shown before, and where Alex Israel is simply called ÔÇ£AlexÔÇØ on the wall text, to avoid needlessly antagonizing the wrong sort of visitor (and, IÔÇÖm told, customs officials.)

ÔÇ£Even this show, here, to talk about America, some people would say youÔÇÖre crazy,ÔÇØ says Salam├®. ÔÇ£In the whole Middle East, you canÔÇÖt see a show like this: people wouldnÔÇÖt know about this artist or the nudity.ÔÇØ

The foundationÔÇÖs first show, titled ÔÇ£New Skin,ÔÇØ focused on abstraction, and, Salam├®┬átells me, local visitors ÔÇ£liked it but it was maybe a bit, for them, too abstract. This show I think is more their visual aesthetic. ItÔÇÖs easier. The relation of love and hate.ÔÇØ

Salam├®┬áis, in his way, an idealist. Yes, these are trophies, but they are something more: As the world becomes more global, and more threatening, itÔÇÖs an attempt to gain some sort of understanding. ÔÇ£Two summers ago, I couldnÔÇÖt sleep at night,ÔÇØ because of ISIS, he says. ÔÇ£You see what they did with the minorities, even the Muslims. They were an hour away from here. I couldnÔÇÖt sleep: your kids, your investments, your art, everything. Everyday it was a different kind of nightmare.ÔÇØ

For a secular Lebanese┬áÔÇö just as for secular Americans, faced with a revanchist Republican party┬áÔÇö itÔÇÖs not clear that anything is necessarily getting better any time soon. ÔÇ£What is going on now is just weird,ÔÇØ he says. He recently saw a show of Palestinian artwork in Berlin, and it brought him back to the ÔÇÿ70s, when there were artists from Cuba showing in Beirut, and ÔÇ£everyone was in miniskirts and nice haircuts and no scarves. It all started with the Iranian revolution. And now everybody is a bit fanatic and closed. Everybody is becoming closed in his own world.ÔÇØ