Are you happy? Would you give up life as you know it to zip back to some idyllic teen summer and laze on the arm of a sorely missed first love? These questions salt the bedrock of Frank Ocean’s work, from the Coachella romance of “Novacane,” breakthrough single from a mixtape literally titled Nostalgia, Ultra, to Channel Orange, an album of brokenhearted reminiscences set in motion by a PlayStation firing up a game of Street Fighter. On record, Ocean is constantly questioning whether or not his best life lies in his rearview, fretful that some burnt bridge or wrong turn has quietly and imperceptibly wrecked everything. The trip from adolescence into adulthood is the forest of these fears, of forked roads to possible futures that dissolve the instant you set about a specific path. Frank Ocean lives haunted by the possibilities.

The new album Blonde is a rogues’ gallery of all the bygone Franks that Mr. Ocean can never be again: In “Nights,” he’s a homeless boyfriend hanging around a significant other in Texas after being displaced from Louisiana by Hurricane Katrina. “Solo” finds him single and enamored of acid and free love, all the while imagining the bad trips, medical and psychological, that befall the careless. Blonde’s constant is a reflexive sense of the burgeoning freedom of self-discovery and also the dangers of chiseling out one’s ideal self mistake by mistake. Doomed musical forebears hang around like cautionary tales: Elliott Smith is quoted in “Seigfried,” and Kurt Cobain, 2pac, and others creep into lyrics elsewhere. But Frank’s not just fixating on tragedy; he’s studying missteps the same way “Solo (Reprise)” guest star André 3000, of Outkast, did in remaining defiantly sober as he came up, while famously declaring that all of his heroes did dope.

André’s appearance here is fitting. Blonde makes a formidable case for Frank Ocean as more than a whip-smart R&B guy the same way Outkast’s exploding tastes helped restore a sense of genre fluidity to black pop music in their epoch. Blonde whisks from the penitent soul of “Nikes” through gossamer waves of strummed guitars in “Ivy,” stripped balladry in “Solo” and “Good Guy,” and electric blues on “Self Control.” The range is owed in part to a list of co-conspirators that serves as a who’s who of recent Album of the Year lists, including Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, Kanye West, Jamie xx, Arca, and dozens more. A reasonable complaint might be that in all its twists, this album very much sounds like 40-some-odd creative voices jibing. But the textures are so dense and frequently fascinating that Blonde scans as meticulously constructed rather than shiftless.

The most peculiar development in an album that touts contributions from gifted hip-hop producers like Rick Rubin, 88 Keys, Mike Dean, and Om’mas Keith, Michael Uzowuru, and Pharrell Williams is that only a third of the songs here have identifiable drums. There are few sounds resembling percussion to be found between the Pharrell and Beyoncé powwow “Pink + White” and the shape-shifting “Nights” six tracks later. (The barely audible kick of “Skyline To” feels more like a faint heartbeat than a drum.) Blonde stays buoyant without drums by employing creative instrumentation and effecting rhythm elsewhere in the mix. In “Ivy,” it’s the palm muted guitar handling the low end. “Solo (Reprise)” lays its keys and booming bass hits over the impeccable time and skittering triplets in André 3000’s rap. Quieter cuts like “Solo” and “Godspeed” subsist on little more than Frank and an organ, reveling in hushed repose as other songs luxuriate in string, guitar, and theremin arrangements.

Frank Ocean was always this versatile. Check the Radiohead and MGMT homage in Nostalgia, Ultra or the Elton John and Paisley Park fan service of Orange’s “Super Rich Kids” and “Lost.” Black pop music — a succession of Lauryns, D’Angelos, Lennys, Princes, Mikes, Janets, Stevies, Jimis, Chucks, and Little Richards — has always razed borders of genre. (The enduring crime of “alternative R&B” as a descriptor is that black music always left space for the rock stripes of Miguel; the psychedelic, post-apocalyptic new wave of Janelle Monae; and the bedroom introspection of Syd and the Internet.) What’s refreshing about Blonde isn’t just how much ground it covers but the open heart and questioning sexuality it carries in doing so. Ocean is neither the first nor the last LGBTQ recording artist to grace the world stage, but he is a rarity in a pop field of play for coming out at the dawn of his solo stardom, where many predecessors felt pressured to stay coy or closeted, stepping into their truth only as the times caught up or the spotlight died down.

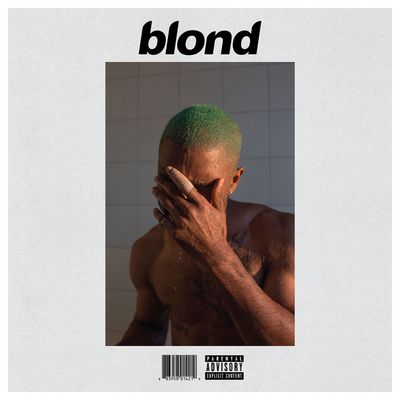

This walk is an integral part of Frank Ocean’s work, from the “love is love” sentiment of Nostalgia’s “We All Try” to Channel Orange’s lost boyfriend yarn “Forrest Gump,” but Blonde feels like a weightier rumination on identity and sexual orientation. The interchangeable use of the masculine adjective “blond” on the album cover and the feminine Blonde as its proper title turns the head. Intentional statement or design accident, the blond/blonde distinction is illustrative of this music’s air of trepidation regarding how far to step out of the straight world. The pained shouts of “I’m not brave!” and “I wanna live outside!” in the contemplative “Seigfried” feel like Frank grappling with his place inside conventional masculinity. He’s dating and tiptoeing into gay clubs throughout the album but only meeting emotionally unavailable men. They’re beneath Frank, but he holds out hope for a better set of circumstances that never seems to arrive. Blonde surveys the messy scene outside of Channel Orange’s busted closet door, where coming out is a battle, but the real war is finding love across the many taxonomies of jerk populating the bars and dating apps.