There’s a fake newspaper ad near the end of Cheap Novelties: The Pleasure of Urban Decay that more or less captures the essence of cartoonist Ben Katchor’s early work. “MAN-SIZED CRIB,” it cries in its headline, above a description of the fanciful product: “There is an infant in all of us and to smooth over those moments of infantile frenzy, nothing works better than a man-sized crib.” To live in a big city is to feel occasional moments of such frenzy: at public infrastructure, at corruption, at decline, at police violence, at those damn tourists in Times Square, and so on. But Cheap Novelties, a beautiful and perhaps even essential collection, is that crib: It comforts and soothes urbanites, reminding us why we pack together in the shadow of towers and bridges.

The book is a collection of the work that first brought Katchor to the fore in the ranks of American cartoonists, containing many of the dreamy, monochromatic two-row strips he had published between 1988 and 1991 in the late New York Press. The comics follow the travels and observations of a stocky, besuited man by the name of Julius Knipl. He’s ostensibly employed in the practice of photographing real estate for clients, but he seems to spend most of his time musing on the ways his city functions and, more important, the ways it used to function before changes great and small swept aside what once was.

Knipl’s city is unnamed, but it’s transparently New York — or, more accurately, a dream of what New York could have been. He spins a rack of postcards in one strip, contemplating fictitious, though plausibly named, points of interest: Binocular Park, the Kitzler Building, Roman Boulevard, the Smolt Bridge. Although there’s a subtle reference to the action taking place as recently as the early 1990s, everything is old-fashioned in a way it hadn’t been even in the years just before Giuliani: All the shops are mom-and-pops, all the men dine in cafeterias, and it’s a damn shame that the price of coffee has risen above a dime.

In other words, the whole endeavor is Borges by way of Bellow, presented with evocatively crude artwork that somehow brings an air of watercolor to its black-and-white scenery. A reader in the 2010s gets easily and joyfully wrapped up in its fictions, stupidly wondering whether such things as public mustard fountains really did exist at some point. Knipl is fixated on the details of his city and its changing nature, sometimes complaining about how the burg has changed, but always regarding it with tremendous respect.

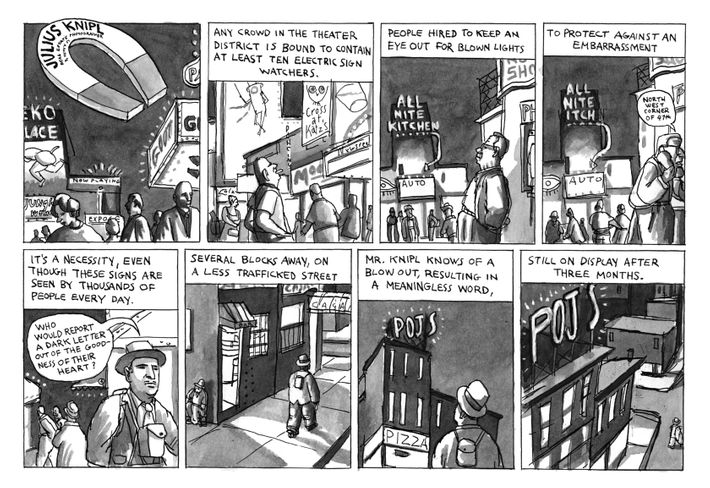

He doesn’t rail against city hall or incoming gentrifiers; he’s too concerned with men who keep watch on theater-district lights to note when they blow out, or his frustration with a local campaign to do away with the sale of day-old bread. He empathizes with vendors of eight-foot-tall balloons who can’t figure out the best spots for selling their wares and he repeatedly orders something called “Herbert Water” from soda shops, only to find it has disappeared from menus. “The conscience of the city hovers above his hot coffee,” a narration box reads at one point, but Katchor could just as easily have replaced that second word with “consciousness.” In our modern parlance, one might say Knipl is all about mindfulness: maintaining an awareness of his world that all of us can so easily lose when we become wrapped in routine.

To read Cheap Novelties in 2016 is to feel nostalgia about nostalgia, to weep at the notion that our memories fade and that the past cannot always be preserved in photos or museums. As the world moves forward, rose-colored glasses can only see back so far before the horizon disappears. At what point does the statute of limitations on lamentation pass? People long for the danger of the old 42nd Street, but is anyone left to personally long for the synagogues of the 1910s? Given that none of us today ever saw Manhattan’s very first Chinese-owned laundries, wouldn’t any of our affection for them be viscerally indistinguishable from Katchor’s for made-up candy stores?

Actually, there is one big difference: There are no Chinese people in Cheap Novelties, nor really any characters of color. This is a series of distinctly white longings. It’s not exactly a case of whitewashing — the tales have a distinctly Jewish feel, and hearken back to an era when Jews were not considered white. Readers can see Cheap Novelties as a love letter to a time before an entire population gradually subsumed itself into whiteness. Even so, one of Old New York’s joys lay in the fact that ethnic enclaves often melded into one another, defined more by class than color — and when they couldn’t meld, there was conflict, something wholly absent from Katchor’s placid set of miniature narratives.

But no one said this was a realistic set of tales. The staccato vignettes, where narration and dialogue noisily intermix with one another like the cacophony of a busy street, are about pure pleasure. Knipl, tubby yet reliably dynamic, looks from under his hat’s brim at a world that feels empirically happier than ours. “Without leaving the city, Mr. Knipl feels a pang of homesickness,” the narration reads at the end of an installment about bus drivers. We share that homesickness, comforted by the fact that, in the pre-fluorescent light of a time-unstuck 24-hour diner, there is joy even in melancholy.