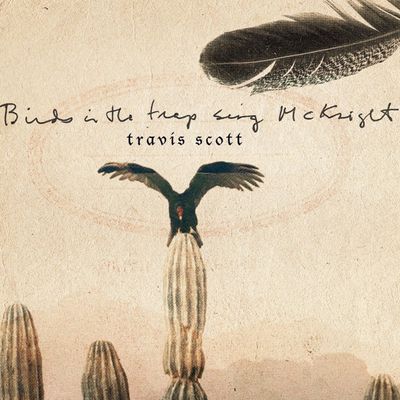

Prescription-drug abuse is modern hip-hop’s not-so-secret shame; for every celebration of the numb embrace of Xanax and the like, there’s another story of a life destroyed by the stuff. The two major hip-hop releases of this week — Kanye West understudy Travis Scott’s sophomore studio album Birds in the Trap Sing McKnight and Kendrick Lamar affiliate Isaiah Rashad’s debut album The Sun’s Tirade — illustrate the opposing ends of the spectrum of pill-era hip-hop hedonism. Scott trips through a rager darkly on Birds in the Trap’s “Coordinate,” while Rashad uses Tirade’s “Stuck in the Mud” to parlay a metaphor about car troubles into a rumination about the alcoholism and prescription-drug addiction that nearly ended his career.

Travis Scott is something of a young rap agent provocateur. His music, where any specific meaning can be gleaned from the camera roll of debauched party scenes his lyrics represent, frequently finds selfhood and freedom in drug-induced euphoria. (This is a peculiar leitmotif for an artist who last year told Billboard he barely drinks, doesn’t touch any hard drugs, and resents the prevailing idea that he does.) His shows are raucous; you might catch him hanging from the pipes on the ceiling of a club, giving his all to show the audience a good time, or recklessly entreating a crowd to break through security barricades to rush his stage at a festival. You never know what to expect other than the extreme.

Scott’s “Coordinate” is noteworthy as one of just a few times that Birds in the Trap doesn’t cede ground to a more seasoned guest. (Birds gets hijacked by everyone from rap gods André 3000 and Kendrick Lamar to singers Kid Cudi, Bryson Tiller, and Cassie as well as brawnier trap contemporaries like Quavo from the Migos and Young Thug. Like the Compton rapper the Game, whose albums lose character amid a parade of famous guests, Travis has a bad habit of absorbing the poetic tics of his collaborators rather than bouncing his own ideas off them.) On his own, Travis sticks to is favorite subject, intoning a mantra about mixed drugs and nice clothes through a veil of Auto-Tune: “Coordinate the tans and the beans in my rockstar skinnies.” Does he know that downers often clip a molly high, or is he just saying words that sound great together? He’s hard to read.

Isaiah Rashad’s dark night of the soul on The Sun’s Tirade feels painfully lived in by contrast. The Tennessee rapper drew national attention in 2013 as the first non-Californian signee of Top Dawg Entertainment, the Aftermath Records–affiliated hip-hop collective that has made stars of Kendrick Lamar and ScHoolboy Q. Cilvia Demo, in 2014, was a promising display of talent, but Rashad seemed to disappear in its wake, opening up the tour behind Q’s Oxymoron album but otherwise unfurling a string of broken promises of a forthcoming debut album. “I got off the Oxymoron tour addicted to Xanax and an alcoholic,” Rashad told Peter Rosenberg, Hot 97 DJ and co-host of the hip-hop podcast Juan Epstein, in August. He’s in recovery now, but the partying set his career back a calendar year and very nearly torched his TDE deal.

Tirade is full of honest introspection, but “Stuck in the Mud” is a sprawling, seven-minute romp in two parts, the first of which deals out a sly metaphor about cars trapped in a ditch that doubles as a word about drug use stalling careers. (“Mud” is drug slang for promethazine.) In the back half, the song snaps from observation to reflection, as Rashad’s voice hollows to a whisper, croaking: “Pop a xanny, make your problems go away, yeah.” It’s coming from a different place than Travis’s anesthetized smirk, though. The substances here aren’t for diversion, they’re a crutch, a coping mechanism. The stress of juggling rap, fatherhood, and vice is pulling the young rapper’s life apart: “One baby mama cool, and one baby mama trip / No matter what I do, there always be some shit / That nigga need a hug, and I just need a fifth.”

The arrival of “Coordinate” and “Stuck in the Mud” on the same day speaks to a hip-hop community grappling with a new era of drug use and dependency. This generation has to contend with the manic jitters of the cocaine ‘80s, the stoned flightiness of the early ‘90s, the promethazine daze of the South’s late ‘90s, and the ‘00s’ penchant for pills all at once. Mixing is a trip, but it’s easy to get trapped. The party’s going strong, but how long can it last?