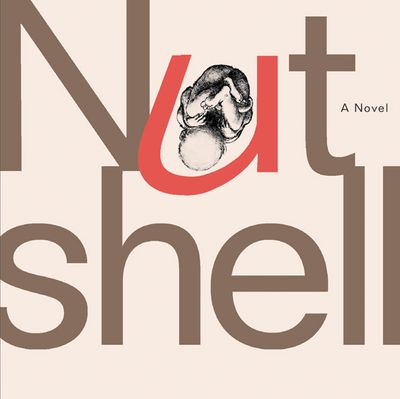

The narrator of Ian McEwan’s novel Nutshell is a male fetus in its third trimester, and his mother, Trudy, is sleeping with his uncle Claude and they are planning to kill his father. So the scenario resembles Hamlet, until halfway through, after the murder is committed and Trudy feels remorse, when she starts quoting Macbeth. The fetus has learned to tell his story by listening through the womb to the radio and to podcasts his mother keeps on all day. That’s why he sounds like a middle-class North London baby boomer: too much BBC Radio Four, especially Melvyn Bragg’s In Our Time. It’s a shame McEwan decided to leave out whatever the plotline of The Archers was when he was writing Nutshell. Chances are it was more intriguing than what he came up with himself.

Claude is a property developer, and his brother John, the cuckolded murderee, is a poet. One is rich, or at least greedy, the other is a debtor, and no English poets are very famous these days, unless you count James Fenton, who lives in New York. So the fratricide symbolizes the ruin of bohemian London at the hands of craven post-Thatcherite capitalism. As doltish as Claude is, it’s hard to feel sorry for John. The former is predatory and virile, the latter flabby and uninspired — which reflects McEwan’s view of English verse of recent vintage (exceptions for Fenton but not Hughes; Betjeman is cited neutrally; Larkin goes unmentioned). “Most of the modern poems leave me cold,” the fetus says of the stuff his father recites. “Too much about the self, too glassily cool with regard to others, too many other gripes in too short a line. But as the embrace of brothers are John Keats and Wilfred Owen.” John also suffers, like McEwan’s transatlantic stylistic uncle John Updike, from psoriasis. His hands are red and scaly, one of the reasons Trudy prefers Claude’s touch, so we’re told.

The emphasis in Nutshell is all on the stunt narrator. The murder story is thin to the point of parody — John is fed smoothie laced with sweet-tasting antifreeze, with props planted to make it look like a suicide — and the authorities unravel it in a matter of hours (any Londoner knows that even smoothie shops are surveilled by CCTV). The fetal narrator is the sign of a writer overcompensating for his own perceived conventionality. Which is itself an interesting phenomenon. London may have been one of the primary staging grounds for modernism, but many of the players on that scene were Irish (Yeats) or American (Eliot and Pound) and England has never been a nation of innovating vanguards. Its movements tend to be reactionary — like the Movement poets and the Angry Young Men of the 1950s — and its innovators, whatever their social milieu, have tended to be aesthetic loners, at least in their own land: Virginia Woolf, Henry Green, B.S. Johnson, Ann Quin, J.G. Ballard, Will Self, Tom McCarthy, Adam Thirlwell (not to mention the unclassifiable genius of Kazuo Ishiguro). The majority of English novelists are conventional creatures, and it’s no accident that the most celebrated English writer of the moment, Hilary Mantel, churns out costume-drama books, ready for stage and screen on delivery. McEwan too had his biggest success with the costume drama Atonement (2001).

But in fits of compensation for English conventionality we do sometimes get what passes for experimentation: See the backward-running narration of Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow or, to rather better effect, the numbered chronological essaylets of the third part of Zadie Smith’s NW. Stunt narrators are at least as old in England as Adventures of a Shilling (1710), a time-honored convention themselves. In Nutshell McEwan hasn’t failed by risking formal originality but by stuffing his book with his own shopworn chauvinisms and not a few pervy bits. Their heightened diction indicates that he took most delight in composing Nutshell’s many fetal-POV porn scenes:

Not everyone knows what it’s like to have your father’s rival’s penis inches from your nose. By this late stage they should be refraining on my behalf. Courtesy, if not clinical judgement, demands it. I close my eyes, I grit my gums, I brace myself against the uterine walls. This turbulence would shake the wings off a Boeing. My mother goads her lover, whips him on with fairground shrieks. Wall of Death! On each occasion, on every piston stroke, I dread that he’ll break through and shaft my soft-boned skull and seed my thoughts with his essence, with the teeming cream of his banality. Then, brain-damaged, I’ll think and speak like him. I’ll be the son of Claude.

Such passages recur about every 20 pages. Then there’s the teeming cream of McEwan’s banalities — a phrase that neatly captures the vices of McEwan’s always fluid style and his preference for ecstatic diction even when it’s obviously disgusting. (An earlier example, from On Chesil Beach (2007), in which the hero Edward is “mesmerized by the prospect that on the evening of a given date in June the most sensitive portion of himself would reside, however briefly, within a naturally formed cavity inside this cheerful, pretty, formidably intelligent woman.”) McEwan’s prose is always smooth — you can almost see the sentences arcing like sine waves — yet there’s also something drab about it. The fetal narrator can’t see the outside world, though we are told the novel takes place during a hot summer (it’s never really hot in London) but McEwan’s prose always leaves the distinct impression of the gray London sky on a rainy day and the beige fields of Regent’s Park in winter. In that sense he may be the perfect English writer.

By indulging the narrator’s incessant digressions, McEwan has used the fetus to make Nutshell a container for the things on his mind in the laziest of ways. The fetus loves adverbs and loves to call attention to his own gratuitous use of them. He worries a bit about global warming. He despises terrorists. He spends a chapter mocking campus-identity politics. He thinks Albanians are brutes. He’s an atheist of the Hitchens/Dawkins school. He listens to Claude, a xenophobe, and John, a tolerant liberal, discuss immigration. Trudy is an alcoholic, and the fetus goes on about the wine she drinks (he especially loves a Sancerre contact high) almost as much as he does about her sex with Claude. Most of the same liberal North London baby-boomer hobbyhorses were on display in Saturday (2005) but in that book McEwan at least took the trouble to implant them in a dramatic framework (if a rather preposterous one). Even those familiar readers of McEwan awaiting one of his signature final twists will be disappointed. Perhaps needless to say, the baby is born. It at least has the side effect of shutting him up.