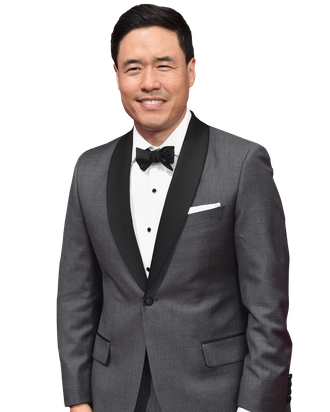

Fresh Off the Boat left off last season with the Huangs about to take off for Louis’s brother’s (Ken Jeong) wedding in Taiwan. Season three picks up in Taipei, where the show traveled to film its premiere, a move that allowed the show to fully explore the identity crisis that occurs when immigrants return to the homeland years later (read Maria Elena Fernandez’s on-set report on the episode here). On this week’s episode of the Vulture TV Podcast, Randall Park joins Maria Elena and E. Alex Jung to talk about what it meant to film this episode in Asia, his own experiences traveling to the motherland growing up, and why, as a Korean-American, he initially hesitated to play a Taiwanese-American. (Listen to the conversation below, which begins at the 30-minute mark.)

Maria Elena Fernandez: The Fresh Off the Boat premiere — if you could tell us a little bit about the episode, if you could talk about some of the themes we can expect.

Randall Park: It explores a lot of themes you don’t find on TV. Definitely not to my memory, as far as things like the immigrant experience, and when you leave your home country and create a life in a new country, you end up not belonging to either. It made me think a lot about my own family, and my parents in particular and their experience. I always wondered as a kid — we went to Korea when I was really young but after a while we just stopped going. And my parents haven’t gone in ages. And I never really understood why.

E. Alex Jung: What was it like for you when you went to Korea?

I went when I was like 10 years old. It was actually kind of a traumatic trip for me because I remember feeling completely out of place. At the time Korea was very different than it is now. It was a lot more country, and a lot more third-world, I guess. I remember there not being toilets — there were holes in the ground and we’d wash ourselves with buckets. And the food was completely foreign to me. I was born and raised in Los Angeles, so it was strange for me at the time.

MEF: Growing up, did you speak Korean and eat Korean food at home, or was your family more Americanized?

We ate Korean food, for sure, but I would say my family did veer more towards the Americanized — my parents were more Louis’s than Jessica’s growing up. They had non-Korean friends. And we’d go to Koreatown maybe once every other week, just to go to the supermarket, the Korean market, to get food. But outside of that it was pretty much a standard Los Angeles kid upbringing.

MEF: So they learned English and you spoke English at home?

Yeah, they would speak Korean to me too. But I would respond in English for the most part. It was this mix of Korean and English that they’d speak to me.

EAJ: The classic Konglish.

Yeah, the Konglish, that’s right.

EAJ: It’s a jarring experience, I think, to go back to your parents’ home country when you’re really young, because I don’t think you really understand the significance of it in a lot of ways. But I do think it has a different value when you get older. Even in the show, the children have a vastly different relationship to going to Taiwan than their parents do.

Yeah, for the kids in the episode it’s like a vacation almost. But for the parents it’s like, “No, no, we’re going back home.” And they say that for their kids as well, like, “You’re going back home, too.” But the kids can’t conceive of this being their home.

EAJ: And it’s not — sort of. [Laughs.]

RP: Yeah, it’s definitely not. It’s a foreign place to them. And the deep thing about the episode is that we slowly learn that it’s becoming a foreign place to the parents. They’ve become more detached than they thought they were going to be.

EAJ: With immigrant parents, too, there’s this idea that they crystallize where the country was when they left, and the idea of Korea or Taiwan or wherever will be this idea that they had maybe back in the ‘80s or the ‘70s when they first immigrated, and the country itself has changed drastically.

Oh, for sure. I know that’s the case for Korea, at least when we were kids, and I saw a glimpse of my parents’ Korea. But today, it’s, from what I’m hearing, such a different place. There’s Wi-Fi everywhere you go, and it’s technologically advanced in so many different ways. I imagine that my parents have no connection to it right now.

MEF: Randall, one of the things we touched on when we were in Taipei was how you watch the show through the lens of the boys because you can really relate to them. Could talk a little bit more about that?

I grew up in west L.A., close to Culver City. And when I was growing up it was extremely diverse. If you look at my group of friends it was every race represented. It was different from any experience in the show in that way. But I did identify with Eddie’s character on the show, in that there weren’t a lot of other Asian kids in our group at least. And that premiere episode, like the lunchroom scene where he comes to school and he opens his lunch and all the other kids freak out, that happened to me, you know?

I remember as a kid I loved kimchi. It wasn’t weird to me at all because it was in our house all the time. There was never a second when a huge jar wasn’t in our refrigerator. I remember bringing it to school, and that just did not go over well at all. A strong, overpowering scent. So yeah, experiences like that really connected me to Eddie. And also, I grew up more in the ‘80s — his love of rap music and hip-hop culture, that was definitely pervasive when I was growing up.

EAJ: You and Ken Jeong have such a great chemistry onscreen in the episode.

We’re great friends, we’ve known each other for years. We met doing stand-up way back in the day. We have different comedy energies — Ken is definitely way more out there and energetic and puts it all on the line, and I’m a little more reserved comedically. The two styles are fun to play off and to bounce off of each other.

EAJ: A lot of the themes that your character, Louis, deals with in the episode have to do with this idea of, What would it have been like if I had never left? I’m wondering how you think about those questions in your own life. Do you wonder what it would’ve been like if you’d been born in Korea and what your life would’ve been like?

Not so much now, but growing up I definitely would think about that. Especially when I would experience something — you know, challenges or forms of racism that really got me down or made me feel like, Gosh, there’s no hope for me in this situation. I remember distinctly thinking, Why did my parents come here? They always say it was for me. They always say it was for their kids, and they put us in these situations where we have no control over how we’re being treated. There’s a line in the show where Louis says — it’s one of my favorite lines in the show, where he’s regretting having made the move to America — to his brother: “We are the white people here.” [Laughs.]

EAJ: That is quintessentially in a lot of ways the Asian-American experience. And it is a very American experience.

Definitely. And I have friends who are Korean who pretty much spend their entire lives, or at least their adult life, in Koreatown. It’s almost like being in Korea, you know? And they have such a different view of what America means to them. Because they’re in this world where they’re a little more protected from things that I experienced growing up. They don’t have the same thoughts of, What if I was in Korea right now? So it is interesting how even here in L.A. or New York or in any city with a thriving Asian community you can kind of almost sidestep those questions.

MEF: I know you have a graduate degree in Asian-American studies. I’m wondering why you decided to pursue that?

When I was at UCLA, a professor there encouraged me to write, and so I looked into specializing in creative writing in the English Department. And through that I started writing plays. Meanwhile, like a lot of college kids, I was discovering my identity and questioning things a little more. And the merging of that happened when me and a few friends decided to form this Asian-American theater company on campus. That’s how I kind of discovered acting for the first time. We cast these original plays that we wrote, and we’d need these small parts filled, and we’d actually take on these small parts. I just had so much fun onstage and kept doing it from there, while still being immersed in academia and Asian-American studies. I ended up going into the Master’s program for Asian-American studies at UCLA, in part because I was passionate about it, but also because I wanted to keep acting in the theater group that we founded. I’d say midway through my graduate studies I just felt like so much of what we were talking about in Asian-American studies, we were just really in this bubble. We weren’t changing things in the way in which I felt like I could contribute and the way in which I wanted to change things. And I so fell in love with writing and acting. I felt like, Oh, this is the way to do it. Years later is when I committed myself to acting. And it’s just so ironic that I’m on this show now that merges all these interests and passions of mine. It’s pretty incredible.

EAJ: I was looking at your IMDb page, and you played a lot of doctors early in your career. When do you feel like your big break was, or your moment when things felt viable and like you could really do this?

The biggest one for me was probably Veep. Even though I wasn’t a regular, I was recurring, and those first few seasons, especially that second season, is when I was in it a lot more, playing Governor Danny Chung. And it’s one of those shows that’s so respected and so adored by the industry and the comedy community. It played a key role in getting me seen within the industry. That was definitely a turning point. But you know, it may slow down. I don’t know. I just go along with the ride because the ride is so unpredictable.

EAJ: And in general, you can tell me if I’m wrong or not, but it seems like there’s more of an awareness in Hollywood in casting to tell stories with more diverse casts. Do you feel like that’s true?

I definitely feel like that’s true. The consciousness of those issues, it seeps into the mainstream. I don’t think the full effect of that has been realized yet. It’s happening right now. And it’s a slow process, but with that being said, there’s definitely a lot more opportunities out there. The next step is creating more opportunities and more lead roles. That’s a big hurdle, especially in the movies. But it’s slowly happening, and I don’t think there’s any turning back at this point.

EAJ: Well, that’s heartening.

I mean, that’s my opinion, of course, but who knows? I remember in the ‘70s or the early ‘80s there were a lot of viewpoints represented on TV. And I don’t know what happened. I don’t know what happened in the ‘90s. I mean in the ‘90s we did get All-American Girl, that was monumental. And after that it wasn’t for another 20 years until our show came along. But I’m confident there’s no turning back. The country is in a different place now. Or so I hope. I haven’t gotten too much flak, if any, from the community in regards to being a Korean-American playing a Taiwanese character. I know there’re definitely people out there who find that problematic and I totally get it, but I was wondering if that would be an issue in Taiwan. And I didn’t experience any of that out there or get any inkling that it was. I don’t know if it’s just because I didn’t meet the people who would be offended by that or if there’s just more of a Pan-Asian consciousness in regards to entertainment out there — I’m not sure.

EAJ: It’s interesting: How much do we subdivide this representation of, can a Korean-American, for instance, play a Taiwanese-American? What was your logic or thinking when you were taking the role?

It was a problem for me, for sure. And early on I talked to the producers about it. I remember having that conversation, I think with Melvin and definitely with Eddie [Huang], because Eddie was more a part of the show at the time. I remember going into his office and saying, “I don’t know if this is right. I don’t feel right playing this character.” But he was so supportive, and the fact that it was his father that I was playing, and I remember him saying, “No one else can play this part but you.” I really took that to heart. I took that and held that close to me, especially early on when I was having trouble with that. But you know, I still have a little trouble with that at times. I guess the goal is that, eventually we can be at a place where we won’t see white people playing Asian people anymore. We’re not there yet [laughs]. But in an ideal world you won’t see a Korean-American playing a Taiwanese character, especially an immigrant character.