There’s a moment late on Meek Mill’s DC4 that seems at once incidental and revealing. Halfway through “Tony Story 3,” the mixtape’s penultimate track, Paulie, the narrative’s protagonist, finds himself alone in a parked car in the darkest hours of the morning. His driver’s seat is all the way reclined; he’s lurking while waiting for one of his kept women to arrive at her residence. Kee, he’s deduced, has been telling the police about his drug- and gun-related crimes, and Paulie plans to murder her to cover his tracks. His freedom hinges on her death, but even so his emotions are getting the better of him: “She on the way, he feel a way, this was one of his whores / And since he been on the run, he been fucking them more … / Thinking ‘bout her, if she come, open the door / Take a deep breath, I know what I’m doing.”

The shift in narration from third-person to first-person in the last line is startling, but on closer examination it seems more than sensible, and not just because Meek’s delivery depends on taking a lot of deep breaths. The upper-echelon dealer/enforcer and the A-list street rapper/celebrity share a sense of stress from heightened attention so intense that it blurs the distinction between them. If Paulie’s paranoid about surveillance and his affiliates are being questioned by the police, Meek, for the last year and four months, has been under relentless scrutiny of a somewhat different, but no less pressing, type. Since exposing Drake’s use of ghostwriters and losing the initial rounds of the subsequent rap beef, the Philly rapper has had to endure levels of scorn that would send most people reeling. Ancillary beefs with Beanie Sigel and the Game have sucked up air in recent weeks. It’s no surprise that he could empathize so strongly, and at such length. Despite running for four and a half minutes without any hook, “Tony Story 3” is never less than engrossing. Like DC4 as a whole, it’s a renewed demonstration of Meek’s considerable (and often considerably overlooked) talents. He’s not just declaring that he’s still on top, but displaying how he rose up to begin with.

References to Drake are gratefully absent on DC4, but the Toronto pop star’s influence is nonetheless felt, if only in opposition: Recent Drake nemeses Tory Lanez and Pusha T pop in for a feature, while Quavo, whose Migos were Drake-jacked for their “Versace” a couple years back, shows up as well. Quavo’s appearance on album highlight “The Difference,” can be seen as highlighting the absence of Future, Meek’s former collaborator and Drake’s current tour mate: With its booming-bass-and-glowing-keys 808 Mafia production, the track is echt Future, but with the Lord of Lean otherwise occupied, one of the Dukes of Dab will have to do.

In general, though, the focus is on the music, not the beefs. Big Meech, the imprisoned Black Mafia Family crime lord, sets the tone early on with a speech advising patience in the face of trifling provocations (“I don’t need you to be a gangster, I need you to be a man”), and it’s advice the artist heeds throughout: “I’d rather kill them all with success and give them knowledge than throw it all away for a sucker, cause we the hottest.” Tempered by experience, Meek’s impulsive tendencies are channeled more fully into his songs: The more he proves himself in art, the less point in complaining over social media.

The beat selection is as assured as the language flowing over it. Heavy, angular, and substantial as a Humvee, Meek’s delivery, for all his modulations (and he is capable of modulation), is naturally limited by its weight; it’s not maneuverable to the same extent as that of his mentor Jay Z, who’s lighter, or his label boss Rick Ross, who’s more rounded. Though he’s a monster a cappella, when it comes to actual songs Meek has to rely on producers to supply a degree of buoyancy and flexibility that his voice can’t convey on its own. Thankfully, though, Ross’s gift for finding great beats has rubbed off on his lieutenant. Meek’s affinity for classical arrangements of piano, chorus, and/or strings is strong as ever, and he still forms stable compounds with the booming bass typical of Southern rap.

Most striking, though, is the production on mid-collection deep cut “Blue Notes,” which samples a blues hook and blues guitar solo to great effect: Against such a backdrop, Meek’s enumeration of his weariness and woes (“No disease but I’m sick of cells”) resounds with special keenness and depth. He’s never been a great innovator. What he does excel at, though, is sustaining a worthy tradition; the mantle of hard-core street rap fits his shoulders well. As the consonance with classical and blues suggests, the strength of age becomes him.

For many it’s been easy to neglect that, for all his impulsiveness and volume, Meek has always been an uncommonly thoughtful writer capable of seeing his environment and his life with a sense of broad perspective. He doesn’t always shock with new content, but he clarifies by reiterating what’s already happening, and has happened: His music often constitutes a chronicle of the history surrounding it. Some of Meek’s most stirring songs are elegies which highlight, in some form or other, the centrality of homicide within this heritage: His father was murdered when he was a child, and both Louisiana rapper Lil Snupe and Detroit rapper Dex Osama were killed soon after being signed by Meek to his Dream Chasers label. His insistence on chasing dreams and displaying brilliant jewelry is also, directly or subtly, an invitation to see the reality and darkness preceding them, and he comes into focus as an artist only insofar as one recognizes the existence of this background narrative. The reason why Paulie is the main character in “Tony Story 3” is because Paulie killed Tony in the original “Tony Story” in revenge for Tony’s jealous killing of Ty, Tony’s partner and Paulie’s cousin, and because Paulie killed Tony’s vengeance-seeking younger brother in “Tony Story 2.” By the end of “Tony Story 3” Paulie, wounded and arrested with charges pending, is bracing himself to survive yet another assault: “Got him in the County, Tony people ‘hind them walls too / And they say his little cousin Crippin’, banging hard too / And Paulie killed his favorite little cousin back in Part Two.” Meek’s art is anything but one-dimensional or superficial: There’s a violent history in his money talk, and an economy in his language. His bangers are superb and immediate (DC4’s “Froze,” for one, looks to be a surefire hit), but appreciating him in full requires more time.

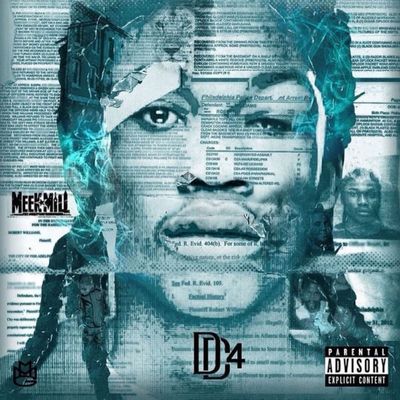

Though known as the city of brotherly love, Meek’s home city of Philadelphia is, as he illustrates, a place where brotherly love and fratricidal violence are two faces of a single banknote; it was no accident that the cover of his last album Dreams Worth More Than Money featured a $100 bill set against a blood-red background, nor that the profile of his fellow rich, hardworking Philly icon Benjamin Franklin should appear on that bill. Though later usurped by New York, Philadelphia was once the financial center of the United States at a time when the vast majority of American wealth was derived from slavery, and money in Meek’s lyrics, as in American life at large both then and now, has a frightful power akin to that of alchemy: It can turn noodles into pasta and tuna into lobster, but it can also turn friends into enemies and human beings into monsters.

Whether America is getting better over time is still questionable indeed, but Meek is definitely improving with time: the bars (often dactylic) on DC4 are as formidable as ever, and the peaks and valleys of his earlier collections have given way, as in Dreams Worth More Than Money, to prolonged elevation. There’s a dip in quality running from midway through the third quarter, but it’s hardly abysmal, and the collection finishes as strongly as it began.

Reports of Meek’s demise have always been exaggerated. Drowned out by the Drake-related fracas was the fact that Dreams Worth More Than Money was uniformly excellent; the pair of 4/4 EPs he released early in the year have aged well. Like most recent high-profile collections in rap and R&B, DC4 demands ingestion as a single, solid unit. The gap in quality between any two given tracks is smaller than ever. Whether in terms of delivery or content, Meek will always be tagged, rightly, as heavy; the difference now is that he’s no longer chunky. Small wonder, then, that his core fans have remained loyal and passionate, or that DC4 should vindicate their faith. All heaviness aside, what stands out in his voice is a sense of hopefulness and responsibility that seems especially heartening in the light of his tribulations: the police-inflicted savagery, the deaths of friends and family, the betrayals, the torturous captivities imposed on him by a racist court system. It’s entirely true that, as he states on the mixtape’s hardest anthem, “Shine,” that “If it wasn’t for this music, I’d probably be dead,” and with or without music, he’s haunted by death regardless. But what rap has given him is more than just wealth: It’s a chance to follow through on his determination not to be forgotten. If he has to repeat himself in the process, that’s just the cost of doing business. Compared to the scale of the legacy he’s built, it’s a small price to pay. He knows what he’s doing, and he’s doing it well.