I met Andy at a party in 1995. Soon afterward, he phoned the host, a mutual friend, to get my number so he could invite me to a play. As it happened, the mutual friend, hearing the description of Somewhere in the Pacific, a gay–World War II–sailor drama at Playwrights Horizons, grabbed the extra ticket for himself, so I didn’t go out with Andy until a couple of weeks later, and then only to a movie. But in the ensuing 21 years we’ve seen more than 1,000 shows together. It has often been my job to see them, but we would probably have gone anyway, or to as many of them as we could have afforded. Not just for the entertainment or enrichment; God knows, those have been spotty. But of all the places in the world where one may share important experiences in public — concert halls, natural monuments, political gatherings — the theater in New York is the only one that allows us to feel completely comfortable, as gay men of a certain vintage, holding hands. The theater, with its relatively small and fairly homogenous audience, has been a safe space, the safest space, for us.

But should it be?

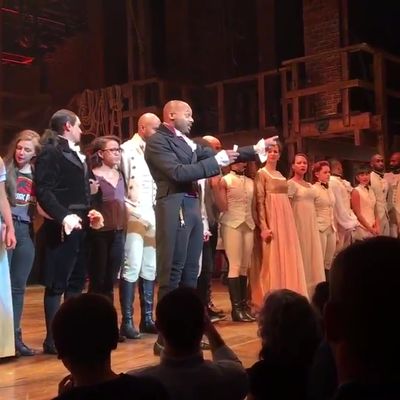

The great stage director Peter Brook did not title his 1968 book about theater The Safe Space. He titled it The Empty Space, because emptiness, he wrote, is all that’s needed to make theater happen. The unspoken corollary is that anything unnecessary that’s brought into a theater detracts from the drama taking place there. I thought about this over the weekend in part because I’ve been in some extraordinarily unempty spaces recently; the Broadway incarnation of Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812 that opened a week ago fills the Imperial with a Czar’s treasure of gorgeous kitsch. (Tolstoy is in there somewhere, too.) I also thought about Brook because of the Hamilpence/Trumpilton kerfuffle on Friday night, in which, as you no doubt know, the vice-president-elect attended the hit show Hamilton with his family. There he was booed by members of the audience, and cheered by others, before catching, as he left, at least part of a curtain speech made by Brandon Victor Dixon, the evening’s Burr. The very respectful one-minute address, written by Lin-Manuel Miranda, welcomed Pence but also expressed the concerns that many on the left, and surely all of the cast, have about the upcoming administration, in which he will be a key player.

This was a very strange turn of events, and not just because the theater so rarely intrudes into the wider public sphere beyond arts pages and chat rooms. It was also strange in that Pence’s visit and the cast’s response to it completely flipped the polarities of “emptiness” that usually prevail at Hamilton and indeed on Broadway generally and in most American theaters. Few of these venues are ever really “empty” because most of the people who buy tickets arrive with fully formed ideas that are then endorsed by the play they encounter. Work may be challenging aesthetically but rarely, to a paying audience, politically. (If there were a theater in New York that regularly programmed right-wing plays, would you subscribe?) The empty space, when it is a commercial space, is usually so cluttered with preconceptions that it is, in fact, a closed space, an echo chamber, useful for amplification and morale, useless for argument.

This case was different. The reactionary politician — one can’t overstate the grotesquerie of his record as governor of Indiana — put aside his close-mindedness at least long enough to enter the Richard Rodgers Theatre without prejudgment, to see a show that is widely known to espouse (and embody) a liberal ideal of inclusion and acceptance. (He later said he though it was great.) Meanwhile, it was the cast who felt it necessary to bring external matters — their understandable fear — into the space. Pence’s presence, which theoretically ought to have been irrelevant, altered the crowd’s reaction to many moments, including the show’s explicit endorsement of immigrants; it thus became the central drama of the evening.

We might have had time to consider the hopeful implications of this strange situation had Trump not inserted himself into the story line, as usual appearing to misunderstand what happened but responding with vigorous peevishness anyway. “The Theater must always be a safe and special place” he tweeted, before demanding an apology from the cast for insulting his veep-to-be. This seemed to signal permission for his followers to open a new front in the culture wars, one in which the theater is framed as an elite institution that needs to have its sense of superiority punctured. No matter that the cast of Hamilton is almost entirely nonwhite, and that the evening’s Hamilton, Javier Muñoz, is an HIV-positive, Hispanic gay man. (I guess that’s elite now.) In any case it didn’t take long for Trumpniks to respond to the dog whistle. The next night, during a performance by the Chicago company of the show, a Trump supporter interrupted the song “Dear Theodosia” with his own improvised rap. “We won! You lost! Get over it! Fuck you!”

That was the theatrical paradox laid bare: the empty space versus the safe space. Which is it? A place of conflict or a place of refuge?

In the days since the election, many New Yorkers have likened Trump’s victory to the September 11 attacks, in that both events shattered a fundamental presumption of safety. My reaction, and that of a number of gay men I spoke to, harked back further, if to the same theme. Trump’s irrational outbursts and anarchic tendencies, his vocabulary of bluster and vague threat, took me instantly to the years of my childhood in which I was regularly bullied at school, both psychologically and physically. I knew enough at the time to recognize that I was merely a convenient outlet for the generalized animus of kids who were mostly less privileged than I, with my solidly middle-class life and prospects. But as the epithets evolved from “jerk” to “kike” to “fag,” I also began to feel that my bullies were getting pretty good at their work. Also: Was there ever an apter tactic for destabilizing kids like me than to knock us down from behind and thus scatter our books? The overfamiliarity of that scenario (revisit any episode of Glee) does not lessen its power in linking enmity to education.

And also to the theater; if you took bullied boys out of drama club you’d have only girls left. (Even Miranda, though straight, was bullied in school, by a classmate who later became successful as the rapper Immortal Technique.) The weird and the damaged, the freaks and the fey: Come to the cabaret, old chum! But if bruises from locker-bangings were almost a badge of entry, the more important thing at my school was that the auditorium, where we rehearsed after school and on weekends, was a place no bully willingly entered. For several years of high school, directing anodyne middlebrow shows like The Odd Couple and You’re a Good Man Charlie Brown, I even had the keys. I let people in and could keep people out.

No wonder those of us who first came to the theater as a safe space reflexively want to keep it that way; with the Chicago incident it begins to feel that the bully has broken in. On the other hand, if the space is so safe that no outrageous (or even just difficult) ideas can permeate, and no people not already converted to liberalism will bother, what function can the theater hope to serve in shaping or resisting the Trumpian moment? So invite Pence back, and take him to Lynn Nottage’s Sweat while you’re at it. Bring Bannon to The Color Purple. Perhaps a special matinee of Falsettos for bullies? (Come to think of it, Trump might well enjoy Natasha, Pierre, if only for its autocrat nostalgia.) But keep making those curtain speeches, too. The safe space was fine for holding hands, but the open space is needed for raising them. We’re not in drama club anymore.