Late last week, Margaret Cho went on Bobby Lee’s podcast TigerBelly, where she discussed, among many other things, conversations she had with Tilda Swinton that left her feeling like a “house Asian.” Swinton had contacted Cho, a stranger, because the controversy over her casting as the Ancient One in Marvel’s Doctor Strange had left her perplexed: Why were people so mad? After I wrote about Cho’s comments, Swinton released the email exchange between herself and Cho to multiple media outlets. No doubt, she did it knowing that she would appear eminently reasonable, and indeed, the release was like sounding a dog whistle: Tilda has the receipts. Readers leapt to Swinton’s defense and criticized Cho for acting in bad faith.

But for many people of color, what Cho said made perfect sense, and the release of the emails — an actual act of bad faith — did little to change that. In a thread on Twitter, Gene Demby wrote, “In the emails, Swinton is exceedingly polite and charming in a way that almost camouflages the grossness of what she’s asking.” Indeed, that Swinton writes in personable prose doesn’t alter the fundamental dynamics of what was going on. Nowhere in the emails does Swinton apologize for having done something wrong; she merely recognizes that people are upset, and wants an explanation. She wrote like someone looking for absolution. As writer N’jaila Rhee put it in a private Facebook group for Asian-Americans in the media, “Tilda Swinton is like the final boss of White Feminism.”

The dustup between Cho and Swinton mirrored another social-media debate that started with the news that Matt Damon would be playing the lead role in The Great Wall, a fantasy movie set in ancient China. In response, Fresh Off the Boat’s Constance Wu penned a mini-screed on Twitter about Damon’s casting in the international co-production. “We have to stop perpetuating the racist myth that [only a] white man can save the world,” Wu wrote. “It’s about pointing out the repeatedly implied racist notion that white people are superior to POC and that POC need salvation from our own color via white strength.”

Wu’s criticism was a sophisticated analysis that had shades of Gayatri Spivak’s postcolonial theory to it. More important, her comments went viral and required a response. Matt Damon said that when he had heard about the criticism, he thought it was “a fucking bummer.” But, he said, he soon found a bright spot. “Pedro Pascal called me and goes, ‘Yeah, we are guilty of whitewashing. We all know only the Chinese defended the wall against the monster attack,” Damon said. “Ultimately where I came down to was, if people see this movie and there is somehow whitewashing involved in a creature feature that we made up then I will listen to that with my whole heart.”

For all his sarcasm, Damon never actually addressed the criticism at hand. Nowhere did Wu say that The Great Wall was an example of “whitewashing.” Rather, her argument was specifically calling out the fact that the film is the latest in which white people are inserted into a narrative — fantastical or not — to save nonwhite people. (Indeed, the fact that Great Wall is a fantasy film should make you consider who that fantasy is for.) The white-savior trope is an old, run-down one in Hollywood; for Damon to say, “it wasn’t altered because of me in any way” is naïve at best.

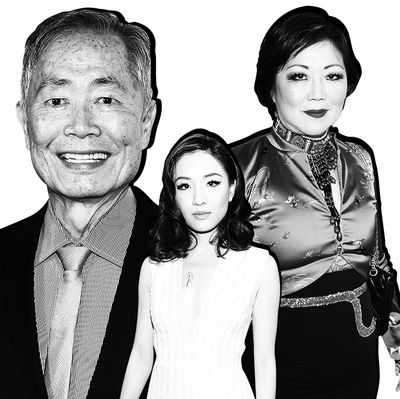

But this is how much of 2016 went for Asian-Americans: Where there was an offense, there was also pushback. When Chris Rock and Sacha Baron Cohen cracked racist jokes at the Oscars ceremony early this year, Ang Lee, George Takei, Sandra Oh, and others penned an open letter in response, using the controversy as an opportunity to discuss racism in Hollywood. When anonymous sources indicated that the upcoming Ghost in the Shell had attempted to use CGI to make Scarlett Johansson “appear more Asian,” Wu was there to call it out. Takei was also vigorous in his criticism of Swinton’s casting in Doctor Strange, calling it “insulting.” All of the actors, including John Cho talking about the mechanics of onscreen racism, elevated the discussion past mere representational politics. While actors like Takei and Cho have long advocated for Asian-American representation, something changed this year. Maybe it was the synergy between actors and writers online, and the simultaneity of such grievances, but the criticism was buoyed, amplified, and heard.

In part, I think it’s because the conversations that have emerged have seen Asian-Americans talking to each other, without the filter a white audience necessitates. What struck me about Cho’s own emails to Swinton was that she was serving a familiar role: Cho listened, offered reassurances, and was polite. By contrast, her appearance on TigerBelly was a conversation between two Korean-American comics — both of whom have gone through the gauntlet in Hollywood — where white people didn’t figure in. Lee told Cho that he thinks of her as his noona, a term of endearment meaning older sister, and they discussed things like the Korean-American community’s scrutiny of Cho after the L.A. riots. (Even Lee’s taking Steven Yeun aside to chastise him was such a hyung thing to do.) They were speaking in shorthand familiar to Korean-Americans as well as people of color, particularly when it came to their experiences in Hollywood. They weren’t operating from a point where maybe Hollywood was racist. They knew it in their bones. And that’s what was really refreshing: that two Asian-Americans felt free to just talk shit.

Next year will bring more controversies, more fights, and more discussions: Ghost in the Shell, The Great Wall, the live-action Mulan, and Iron Fist all début in 2017. (Already, there have been some excellent jokes about this photo of Finn Jones.) But, as Margaret Cho told Bobby Lee, it’s time for Asian-Americans to be making their own stories. John Cho is producing and starring in a drama for USA called Connoisseur, Jon M. Chu is adapting Crazy Rich Asians for film, Daniel Dae Kim is producing a number of shows based off of Korean dramas, and Constance Wu is slated to star in an indie drama by Jennifer Cho Suhr. It’s possible to look back on the year and remember a list of grievances, but it might be better to remember it as a wake-up call. Earlier this year, John Cho told me, “I think, while my career is fucking great for an Asian actor, I haven’t been given the chance to do all that I can.” Here’s hoping to 2017.