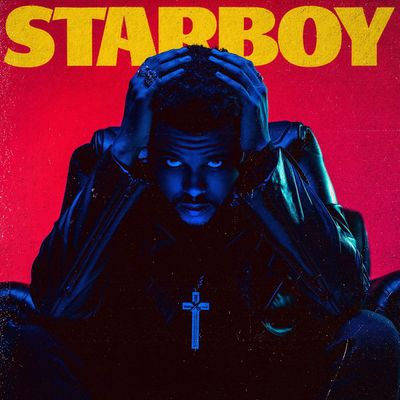

The speed, efficiency, and care that characterized the rollout for the Weeknd’s Starboy were especially welcome coming at the tail end of a year crammed with awkward, mistimed, and otherwise botched album launches from many other leading lights of pop music. Announced in late August with a late-November release date, the album was delivered right on time, and the three intervening months were punctuated by a steady series of sight-and-sound appetizers: new haircut, album art, lead single, music video for lead single, second lead single, SNL performance, bloody bank-heist music video for second lead single, tour announcement, MTV EMA performance, revelation of the full track list, two more lead singles, AMA performance, 12-minute video featuring a medley of songs from the album, Tonight Show performance. Even the Thanksgiving-night release proved to be uncannily timely: To those too sullen about politics to talk at dinner, the music of Starboy would sound like that much more of a relief. The Weeknd likes to spike his music with mentions of various mood-altering substances: The implication is that the music, bedizened by drugs, is itself a drug, whether Adderall, Xanax, promethazine, or cocaine. Tryptophan, it turned out, worked just as well.

The Weeknd has been going about his business in a sleek and punctual manner, and his professionalism has always been marked by an acute self-consciousness. Having released three rapturously received album-quality mixtapes as a freelance artist in 2011, Abel Tesfaye has always known that there was an alternative to dealing with the music industry. But if he was going to sign away his fate to a major label, he was going to do it in full knowledge of what that entailed. The first track on Kiss Land, his 2013 major-label debut, was accordingly titled “Professional.” The lyrics of “Professional” trace out an equation between the career trajectories of a high-end female sex worker and Tesfaye’s own: In the artist’s rendering, each one is a rise, fueled by eroticism, from the anonymity of the underground to wealth and fame. The promise wasn’t just that the Weeknd was signing on the dotted line, but also that he was going to, if he could, make wonderful songs about doing so.

Though “Professional” lived up to this promise, the rest of Kiss Land was a testament to its difficulties. The sweeping, aerial, melodic production coupled with Tesfaye’s diarylike longueurs (hooks were in scarce supply) left little for the listener to hold on to. I’m not a fan of fancifully elaborate metaphors in music criticism, but given how fancifully elaborate the album was, it has to be said that listening to Kiss Land was like struggling forward in a wind tunnel lashed by long, fluttering, sometimes blood-stained blue and black ribbons of silk. “This ain’t nothing to relate to, even if you tried,” Tesfaye keened late on the album in an eerie, double-headed, seven-and-a-half-minute title track, its second-best after “Professional.” But since so much of music is about relating to the singer and there’s nothing to relate to, then why try at all? The commercial failure of Kiss Land didn’t hurt the Weeknd too much. He didn’t lose any fans. But he didn’t gain any either, and aesthetically the album wasn’t better than his mixtape trilogy. There was no point in signing a major deal if he couldn’t make himself a pop star, and if he was going to make himself a pop star, he would have to find and hit different notes.

At this, he succeeded. Last year’s Beauty Behind the Madness, Tesfaye’s star-making collection, restores the strong narrative element of the mixtape trilogy absent from Kiss Land: Instead of uncut alienation, the album describes a path out of it into romantic commitment before relapsing into solitude. The central love arc is the longest section: Featuring three collaborations between the artist and Max Martin, the Swedish Svengali behind a bevy of monster pop hits, its blend of expert production, tender yet not saccharine verses, and rich simple hooks proved irresistible to radio. Embracing love and pop, Tesfaye had earned himself the golden ticket he had entered the music industry to obtain. The price he had to pay was a reduction in heavy rhythms and the concealment of his more menacing tendencies. The cruelty evident in his earlier work hadn’t vanished: Beauty’s sweetly strutting “Tell Your Friends” much resembles the icy, trampling 2014 single “King of the Fall,” but dressed in warm, flowing colors, and the album’s romantic narrative, in its single-minded focus and execution, evinced a curious extremism that verged on the religious. But as suggested by “Earned It,” an early hit that originally appeared on the 50 Shades of Grey soundtrack, for the most part his honest sadism had been sublimated into earnest affection. Backed by a battery of major hits, Beauty Behind the Madness went triple platinum, completing Tesfaye’s metamorphosis from dark prince of the underground into pop superstar without sacrificing his artistic integrity.

As its title indicates, Starboy is the first Weeknd album in which the artist’s global prominence is already a given, and given that its Daft Punk–featuring title single is the first track and lead single, one might expect the entire album to take fame on as its core theme. Such an assumption soon proves itself misguided, at least in part. Fourteen of the album’s 18 tracks are devoted not to Tesfaye’s celebrity but to his devotion to a woman, and the remaining four tracks (“Starboy,” “Reminder,” “Sidewalks,” and “Ordinary Life”) are scattered at wide intervals. Though there’s a shift from the fleet-footed grooves — great to have them back — that dominate the first half to the swooping, mid-range ballads prevalent in the second, the transition, over the course of 68 minutes, is gradual enough as to be imperceptible.

Though there’s a discernible progression in content (from less romantically committed to more), Starboy isn’t a narrative so much as a directory, a showcase of the artist’s ability to, as he says on “Starboy,” “take any lane” in terms of sound — rap, R&B, disco, electronic, electroclash, pop, ‘80s pop — and tone: bragging, vulnerable, admiring, pleading, further pleading. If he’s embracing fame, he’s doing so through the surrogate of the female “you” he addresses and, more directly, through the confident execution of roughly a dozen potential radio hits. Versatility and consistency are the album’s central concerns: The album isn’t overly exercised with the state of stardom. Rather it’s more committed to exercise as such, and physical workouts especially: Though the pace and stage props may change (stripper pole, disco ball, solitude, strobe lights, high-school gym on prom night), this collection is clearly for the dancers. Starboy is the longest Weeknd project with the most tracks, but duration-wise that doesn’t mean it doesn’t correspond to the theme of slimming down — its average song length is the shortest.

An embrace of stardom is an embrace of the teamwork and machinery of stardom, and in Starboy this process is literalized in the production. The album’s bookending by two Daft Punk features is a clear sign that, even when not directly involved, the French cyborg duo are guiding spirits. Whatever the genre, the album’s lively yet inorganic soundscapes are strongly influenced by their fusion of the vital and the artificial, and the robot-soul aesthetic is further enhanced by Tesfaye’s willingness to double his voice (known anyway for its unearthly purity verging on the virtual) by pouring it through vocoders. The interest in collaboration is reflected in a supporting cast of writers and producers whose numbers could fill the ranks of a large platoon. Tesfaye has assembled himself a dream team of fellow “professionals.” In addition to Daft Punk, Max Martin and his longtime partners in sound (Ali Payami, Peter Svensson, Savan Kotecha) feature multiple times: Their deft simulations of the sound Quincy Jones once arranged for Michael Jackson strike true on “Rockin’” and “A Lonely Night.”

A set of Tesfaye’s longtime collaborators features even more prominently: The producer Ben Billions is a recent comrade responsible for producing recent hits like “Low Life”; Doc McKinney, the Canadian trip-hop pioneer who produced the Weeknd’s breakout mixtapes House of Balloons and Thursday, has finally returned, co-producing half the tracks and serving as executive producer; and Ahmad Balshe, the Weeknd’s XO affiliate and Toronto native of Palestinian descent who raps under the name of Belly, is credited with lyrical touch-ups on half the tracks. Though it contains multitudes, the album comes off as imposingly cohesive, though a certain impersonality is the inevitable drawback. Production-wise, its closest parallel isn’t the lithe Off the Wall but the muscular Get Rich or Die Tryin’ (also produced by a self-credentialed doctor): It doesn’t entice the listener to enjoy it so much as it compels enjoyment, and it does so with enormous success. Of the 18 tracks, only “False Alarm,” “Love to Lay,” and “Ordinary Life” are anything less than optimal, and even so these three aren’t atrocious to hear: It’s just that their production can’t compensate for inert hooks and a somewhat patronizing tone. Even so, they’re not strikeouts — just infield singles diminished by comparison to a plethora of greater hits.

The surest indicators on Starboy of what the Weeknd stands for personally are the featured guests. With the exception of Kendrick Lamar, who turns up for a bout of relaxed boasting on “Sidewalks,” each featured guest appears twice on the album, as if the artist were defining himself by doubling down on the aspects he shares with each. Just as Tesfaye’s alignment with Daft Punk points toward their shared convergence of biological pulse and mechanical compulsion under the sign of pleasure, the collaborations with Future on “Six Feet Under” and “All I Know” highlight the Toronto crooner’s fraternal relation with the Atlanta rapper: Both men have erased the distinction between rap and R&B, crafting odes to sex workers and promethazine in the same rhetorical tone as their standard celebrations of their own prowess, fame, and fortune. The contrast with Drake, the Weeknd’s fellow Toronto superstar and Future’s recent tour-mate, is illuminating: Drake’s novelty lies in his translation of R&B flirtation and suburban ambivalence into spoken words while the innovations of the Weeknd and Future convert rap’s criminal resourcefulness and angst into sung lyrics. One of Starboy’s brightest highlights is “Reminder,” a track whose sung lyrics, with their self-centered, crew-vaunting, luxury-celebrating tone, could easily double as rap lyrics. Often the difference between Tesfaye and hip-hop artists is one of degree, not kind: His singing voice sounds like the good life, whereas their spoken words only refer to it.

Yet it might be the duets with Lana Del Rey that reveal the most about Tesfaye’s identity as a musician. Much more could be written on this, but for now suffice it to say that both singers are classicists willing to risk kitsch and banality in their pursuit of the mythic and exceptional. They hope, in other words, to excavate archetypes from stereotypes. So there’s Lana Del Rey contributing backing vocals on the aptly named “Party Monster,” cooing to the Weeknd that’s he paranoid, seeing too much in a woman and fearing what he sees even more, and there she is later on an interlude as the Stargirl addressing the Starboy in a coital fantasy. Both artists understand two things perfectly: First, that grand gestures are the only thing that count in music; second, that there’s no way to avoid corniness when it comes to making them. Best to take it head on.

Even their differences are complementary: Del Rey sings as a woman going all-in on love while the Weeknd sings as a man afraid to. (Hard to get more stereotypical or archetypal than that.) What keeps the bulk of Starboy firm instead of flabby is Tesfaye’s realism regarding this reluctance. He doesn’t make music for people in love so much as for people — male or female — who want to be but can’t quite make the leap, and his frankness regarding one’s attachment to their solitude is anything but kitschy — it’s what makes him the most convincing male artist currently active in pop. His ability to speak candidly of the fear and alienation precluding love is what renders his invitations to enter into it that much more convincing and attractive: “You’ve been scared of love and what it did to you / You don’t have to run, I know what you’ve been through.” Even without the water-brilliant music of the Daft Punk production, those lines on Starboy’s closer “I Feel It Coming” would carry weight: With that music, it’s pretty much irresistible. If he’s not the King of Pop today, then no one is.