Learning to Love Cy Twombly

I admit that I have always been a bit skeptical about Cy Twombly. The combination of his inscrutability — all those words and phrases, scrawled and painted over, and grandiose titles referencing classical mythology — combined with the work’s billionaire home-decor market value to speak to something clubby, cushioned, and aloof which I never quite got, or felt I should get, or maybe that I felt that I needed to get. And it’s not just me. Long before he became elevated to the postwar canon, many people found him fussy and off-putting. His shows were often panned, and during a 1994 retrospective at MoMA, museum curator Kirk Varnedoe admitted that many certified non-philistines found his work “truculently difficult” and defended its scratches and doodles as being something your kid could not, in fact, do. Of course, just because he’s become a Gagosian all-star didn’t mean I had to like him too.

It’s not that I didn’t appreciate the gorgeous power of many his paintings: when I first wandered into the room housing his 1978 series Fifty Days at Iliam at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, I felt like I was inside the artist’s head — Shield of Achilles could be a perfect monument to bleak, defiant emotional squall. But seeing the series again at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, as part of a grand retrospective of Twombly’s work which, the curator explained to me when I saw it, won’t ever travel because of how difficult it was to assemble this precious trove in the first place, I had a different reaction, one which took me through the entire show and has stayed with me still: the proud sadness of the man, armored (not unlike Achilles, another well-connected gay man who got that shield thanks to his nymph mother’s outreach to the god Hephaestus) by his lavish erudition. The obscurity and pretentiousness began to seem like a bid for sidelong self-assertion, a shy, even, yes, truculent, peeking through.

Twombly was born in Lexington, Virginia, in 1928. His father was a swimming coach and had briefly been a pro baseball player. Both he and his dad shared a nickname with Cy Young, though its implied aspirations didn’t seem quite as apt for the bookish son, who took an early interest in painting. After graduating from Washington & Lee, he got a scholarship to the Art Students League in New York, where he met his lover, and another artist of palimpsestic tendencies, Robert Rauschenberg. It was the early ‘50s in New York, which was, for artists, becoming the right place to be, and he even did a sojourn at Black Mountain College, the sleepaway camp of the emergent American aesthetic vanguard. He and Rauschenberg also went traveling around the Mediterranean.

Eventually, Twombly settled down in Italy, and, in 1959, married Tatiana Franchetti, a painter herself and art patron; the two had a son, and, we are assured, remained lifelong friends, even after Twombly took up with Nicola Del Roscio, who survives him and runs the Cy Twombly Foundation (its holdings are worth an estimated $1.5 billion.) One of the more telling moments in the show comes in a display case of books and clippings documenting his life: There is a 1966 Vogue profile of him, reclining in a white suit, his wife framed in a palazzo doorway behind (photograph by Horst), which reads: “In certain quarters, where it is assumed that avant-guarde American artists should live in avant-guarde American discomfort … has led to Twombly’s being suspected of having fallen for ‘grandeur,’ and somehow betrayed the cause.” (He died in 2011.)

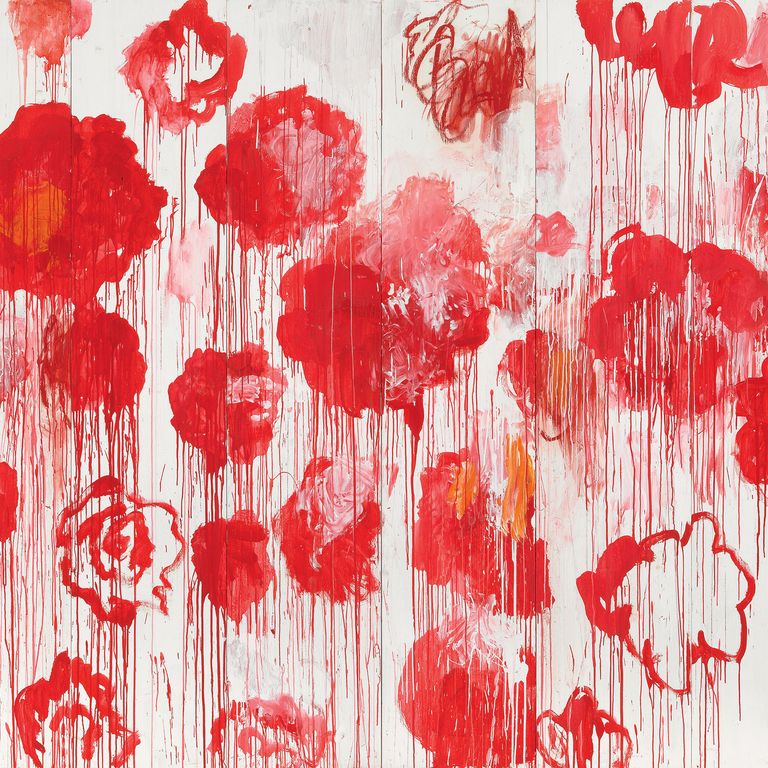

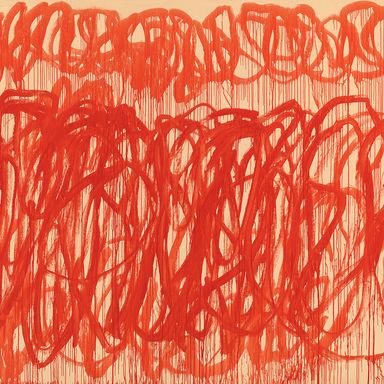

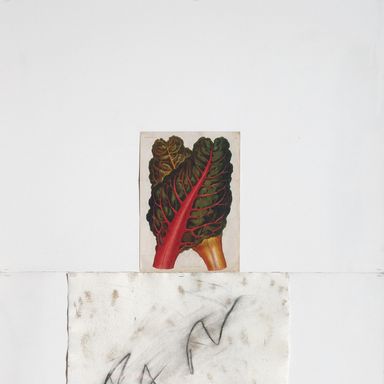

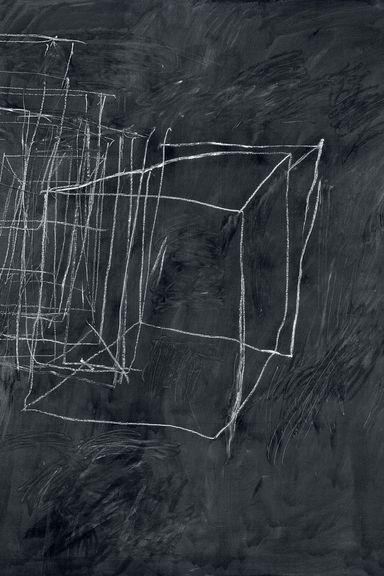

It’s difficult to imagine that arch criticism being leveled at an artist today, but the Pompidou show puts his work into steady, exquisite focus and order. It opens with a 1954 piece titled Sans titre (New York), with its big scribbly eyeball and, snaking out of the chaotic chicken scratch, an electrical plug. And from that moment, he had me. Then, on to the carefully framed drawings he made, apparently in the dark while lying down, the paper resting on his chest. (Now there’s a metaphor for you.) He worked often in series, which is convenient for curation, each room a world. And then, to ever more epic works, and multi-panel series — his version of history painting, filling entire rooms. The Pompidou doesn’t cramp it either. But mostly, it helps to be able to see it all up close, all of the copied and half-buried lines of poetry about longing, all the erasures and bathroom-wall graffiti and the streaks of paint, like tears or bleeding flesh, when the obsessiveness of the man becomes apparent, and the ache of his life — doodles of cocks and balls and buttholes and all — becomes legible. And in the end, you gotta feel for the guy.

Blooming, 2001-2008.

Camino Real (V), 2010.

Untitled (Bacchus), 2005.

Photo: bpk | Bayerische Staatsgem‰ldesammlungen

Coronation of Sesostris, 2000.

Dutch Interior, 1962.

Photo: Digitalisiert von farbanalyse, Köln farbanalyse, Redwitzstr. 7, 50937 Köln, Tel. 0221 - 94 20 240, E-Mail: info@farbanal...Dutch Interior, 1962.

Photo: Digitalisiert von farbanalyse, Köln farbanalyse, Redwitzstr. 7, 50937 Köln, Tel. 0221 - 94 20 240, E-Mail: [email protected]

Fifty Days at Iliam Shades of Achilles, Patroclus and Hector, 1978.

Pan, 1975.

Night Watch, 1966.

Untitled (Formia), 1981.

Untitled (Lexington), 1951.

Photo: Digitalisiert von farbanalyse, Köln farbanalyse, Redwitzstr. 7, 50937 Köln, Tel. 0221 - 94 20 240, E-Mail: info@fa...Untitled (Lexington), 1951.

Photo: Digitalisiert von farbanalyse, Köln farbanalyse, Redwitzstr. 7, 50937 Köln, Tel. 0221 - 94 20 240, E-Mail: [email protected]School of Athens, 1961.

Photo: Robert Bayer; BildpunktAG, SwitzerlandStill Life, Black Mountain College, 1951.