For seven decades, we’ve been studying American novels by talking about “postmodern” and “postwar,” the latter a category that has outlasted its usefulness, at least since the death of Norman Mailer. But in making finer distinctions about books, why wouldn’t presidencies serve as well as decades? You can match the heroes of John Updike’s Rabbit, Run, Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, and Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road with JFK; and you can trace Reaganite excess through Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City and Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero to its derangement during Bush I in American Psycho to the recovery narratives and Clintonian delirium in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest.

The era of George W. Bush had its own myths, and they started to fade as soon as he retired to Texas and took up painting. We’d had our fill of 9/11 novels, and superheroes like those who’d surged into literary texts — as in Jonathan Lethem’s Fortress of Solitude and Colson Whitehead’s John Henry Days — now saturate our screens. There were the “Brooklyn Books of Wonder,” to use the critic Melvin Bukiet’s term for the era’s turn toward the adolescent. There was also a vogue for what we might call humanitarian lit: privileged, often white American novelists telling the stories, and occasionally writing from the point of view, of Third World refugees, as in Dave Eggers’s What Is the What. Perhaps exhausted with depression and its medication as subject matter (see the Gary section of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections), novelists took up neuro-atypical heroes, as in Richard Powers’s The Echo Maker and Rivka Galchen’s Atmospheric Disturbances. It was, above all, a phase of elaborate fictions.

What will we mean when someday we refer to Obama Lit? I think we’ll be discussing novels about authenticity, or about “problems of authenticity.” What does that mean? After the Bush years, sheer knowingness and artifice that called attention to itself had come to seem flimsy foundations for the novel. Authenticity succeeded storytelling abundance as the prime value of fiction, which meant that artifice now required plausible deniability. The new problems for the novelist became, therefore, how to be authentic (or how to create an authentic character) and how to achieve “authenticity effects” (or how to make artifice seem as true or truer than the real).

That we’ve been passing through an era that especially prizes authenticity in fiction is no coincidence. These were years when America was governed by someone who’d written a genuine literary self-portrait, whose identity was inscribed with the traumas of the age of colonialism and its unraveling, whose political appeal hinged on an aura of authenticity and whose opponents attacked him by casting doubt on the authenticity of that identity. Now, as he leaves the scene, we’re troubled by questions of fakeness — a moment of fake news but also a time when the reassurances of big data have proved fallible, when a shared civic reality has cleaved definitively into a pair of mutually distorting digital bubbles, exposing a national identity crisis that America’s left and its writers (most of them creatures of the left) didn’t know, or want to know, was happening. Even the president-elect’s hair seems to be a fiction. No wonder some are pointing to science fiction as the best predictor of what’s to come.

The dystopian narratives of the Trump regime will come along soon enough, but in the meantime, four strains of books have been particularly germane to the Obama years, and they spring from four strategies of approaching the problem of authenticity. First, autofiction: narratives that appear to do away with much of fiction’s familiar scaffolding — plots, scene-setting, the development of characters other than the hero; that eschew familiar modes of storytelling in favor of the diary entry, the transcript, or the essayistic digression; and that collapse the distance between the hero-narrator and the authorial persona by investigating that dual figure’s claims to authenticity. Second, fables of meritocracy, often satiric: social novels and comedies of manners in which higher education and its professional aftermath are both crucibles that allow characters to reveal their authentic selves and alienating systems that strip them of their native identities. Third, many historical novels have been set in the near past, locating in recent decades the romantic grit and violence their nostalgic authors find lacking in the sterile present. And, fourth, a set of narratives have placed the experience of trauma — rape, pedophilia, homophobic abuse, incarceration, the horrors of war — at their center, where it assumes an animating role: Suffering bestows meaning on an otherwise comfortable world. (Of course, these categories aren’t comprehensive, nor are they exclusive — plenty of books could be placed in two or three columns.)

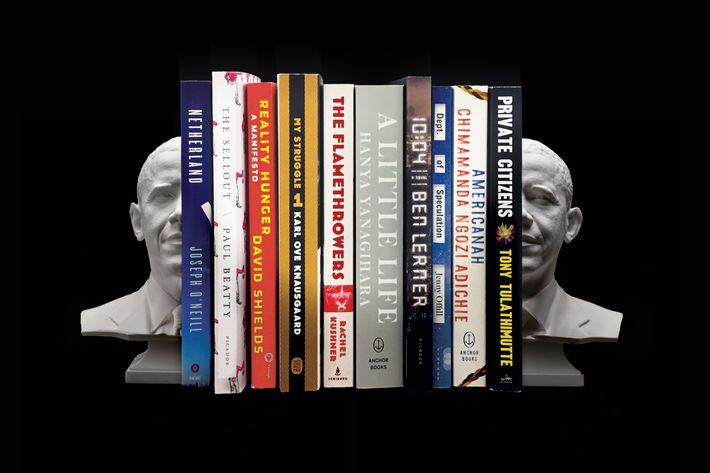

A curious thing about these strategies is that they can be read as responses to the work of critics. Three in particular. James Wood had put forth a theory of hysterical realism in a review of Zadie Smith’s 2000 novel, White Teeth: fictions that prized vitality above all and weren’t afraid to heap stories on top of each other, winking most of the way. In November 2008, Smith published her diagnostic “Two Paths for the Novel” in the New York Review of Books, and the essay reset the terms of the perennial struggle between conventional lyric realism and the avant-garde and identified authenticity as the new grail. The realism of Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland was “anxious,” Smith wrote. “It knows the world has changed and we do not stand in the same relation to it as we did when Balzac was writing.” But the alternative, Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, about the survivor of a traumatic brain injury who conspires to restage particular images from his memory in continuous loops, was tortured, too (“The violence of the rejection Remainder represents to a novel like Netherland is, in part, a function of our ailing literary culture”). Smith also noted that her subjects were two Oxbridge-educated white guys: “two brilliant young men, straight out of college, both eager to write the Novel of the Future, who discover, to their great dismay, that the authenticity baton (which is, of course, entirely phony) has been passed on. Passed to women, to those of color, to people of different sexualities, to people from far-off, war-torn places … The frustrated sense of having come to the authenticity party exactly a century late!” But it’s always too late for the novel, and in the 21st century (as Smith’s new book, Swing Time, shows), the specter of phoniness haunts all fictions and anybody who’s been to college.

Two years later, midway through Obama’s first term, David Shields published his manifesto Reality Hunger, an “ars poetica for a burgeoning group of interrelated but unconnected artists in a multitude of forms and media — lyric essay, prose poem, collage novel, visual art, film, television, radio, performance art, rap, stand-up comedy, graffiti — who are breaking larger and larger chunks of ‘reality’ into their work.” Less theoretical and more ambivalent than McCarthy’s anti-novel but somehow just as strident, it suggested a third way. Composed of fragments, most of them borrowed (sorry, “appropriated” or “sampled”) and altered, the manifesto targeted, among other things, the wall that had been erected between nonfiction and fiction, and the notion that nonfiction delivered something more urgent because it was based on fact. It called for “deliberate unartiness: ‘raw’ material, seemingly unprocessed, unfiltered, uncensored, and unprofessional … Randomness, openness to accident and serendipity, spontaneity; artistic risk, emotional urgency and intensity, reader/viewer participation.” The two key words here are deliberate and seemingly: The idea is authenticity attained through artifice.

Though Shields was able to point to plenty of examples of an “artistic movement, albeit an organic and as-yet-unstated one” in other media — television, music, theater, poetry — his examples from prominent contemporary literary fiction were relatively few. There was Nicholson Baker, and further in the past there was a diaristic collage novel by Renata Adler that would soon return from a long exile out of print. He might have pointed to Chris Kraus, whose novel I Love Dick was then undergoing a revival that’s now culminated in its adaptation for television, or to the work of the late W. G. Sebald, which blended history and personal recollection and whose influence was just beginning to ripple into English. Of course, there had also been a vogue for memoir in the publishing industry for so long that it had become accepted as the status quo and acquired rigid conventions of its own. Shields reveled in the flouting of these conventions, particularly the one that holds that nonfiction should stick to facts. This was one of the reasons, along with his obsequious celebration of his own borrowing, that I was skeptical of Reality Hunger when it appeared. But seven years on, there’s no denying he was a prophet.

1. Mirror Effects: Autofiction

Do you recoil when you pick up a novel and find that the narrator is a writer who lives in Brooklyn and teaches creative writing? When the book chronicles his dating life or her failing marriage and struggle to write a book (perhaps the one you’re reading right now)? When time seems to pass in the novel not according to a string of events that form a plot but according to some stage in the writer’s, I mean narrator’s, life that presaged or coincided with the composition of the book? When the writer’s, I mean narrator’s, diary entries, texts, emails, or Gchats seem to be tossed into the book raw?

To make further distinctions, if I told you the story of the way my rich neighbor got himself killed trying to get back with his ex-girlfriend in parallel with the subplot about my own fizzled relationship with an attractive golfer it happened to align with the real events of my own life (only my friend wasn’t that rich, he just owned an apartment that was good for parties; and he didn’t die but failed to get his ex back and then decided to move to L.A. — rendering him dead to me; and my fling wasn’t with a golfer but with a woman who’d played some tennis in college) — that would be autobiographical fiction. If I told you the same story but full of winking allusions to The Great Gatsby and parodic flights about my neighbor’s efforts to fix the 2017 World Series and his ties to a drug ring (so that’s how he owns his apartment) — that would be metafiction. But if I told you the story of the year I tried and failed to write a modern retelling of The Great Gatsby while growing increasingly suspicious that my tennis-playing girlfriend was sleeping with my rich neighbor and took to walking the city encountering acquaintances and strangers who had their own stories of envy and infidelity, almost entering into an affair of my own with a professional golfer (cue the flirtatious Gchats), when all along my girlfriend was faithful to me and our relationship healed after I gave up trying to turn myself into a neo-Fitzgerald (I was always a phony Fitzgerald) and decided to just be me, on the very day my girlfriend told me she was pregnant (no matter whether all of this were true, or in fact I was happily married and just focused on trying to earn an advance big enough to help put the long-since-born kid through St. Ann’s, though the themes of envy and infidelity reflect my abiding literary interests) — that would be autofiction. (In fact, I’m childless and single.)

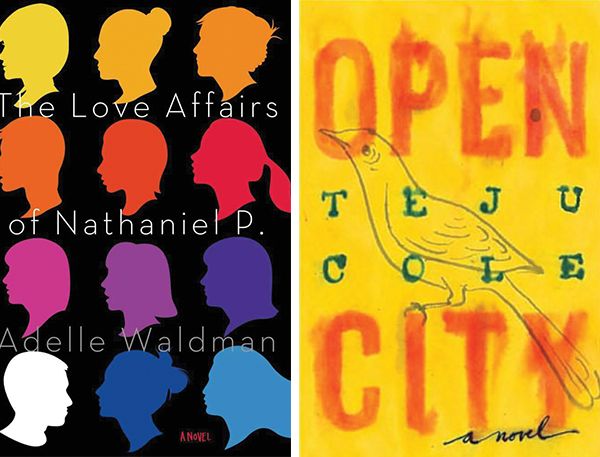

In works of autofiction, the line between the author and the protagonist blurs, and that blurring is central to the experience of reading the novel. There’s an evident hostility to many of the tidy conventions of literary fiction. Plots are submerged beneath the unruly flow of time. Characters other than the protagonist may be reduced to the status of spokes, of interest only in terms of their connection to the central figure. The set piece gives way to the essayistic digression or the journal shard. A roll call: Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04, Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?, Teju Cole’s Open City, Tao Lin’s Richard Yates and Taipei, and the brilliant, fragmentary third section of Smith’s NW.

Or take Jenny Offill’s second novel, Department of Speculation (2014). The book’s first half is told in the first person in diaristic fragments. The narrator is a novelist, wife, mother of a young daughter, a writing teacher who takes a ghostwriting job for a wealthy “almost astronaut.” She’s nervous about the state of her second novel. She lives in Brooklyn with her family, and their apartment has a bedbug infestation. All of this is plausibly the life of a writer in middle age, some of it veering charmingly and sympathetically into cliché (those bedbugs, poor kid). Halfway through, the narration switches into third person, and the story (there hasn’t been too much story so far) follows “the wife” through her suspicions about and discovery of her husband’s infidelity. Why the switch? Even readers trained to distinguish between authors and their characters will have to ask whether the first half is somehow less fictional than the second half. Readers without any interest in the private life of the actual Jenny Offill will still be wondering whether the new framing is a way to put some distance between the author and painful events in her personal life or meant to signal the invention of a dramatic story (of the sort novels perennially tell) that real life never supplied. It’s a simple move, and it has the effect of enhancing the novel’s aura of authenticity even as the book veers into conventionally novelistic subject matter. That is, what might be read as a traditional adultery plot maintains the air of an urgent confession.

Writers too are the heroes of Ben Lerner’s two novels, Leaving the Atocha Station (2011) and 10:04 (2014), Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? (2010), and Tao Lin’s Taipei. Lerner’s narrators speak in the voice of a relentlessly self-reflexive critic (“I’m going to write a novel that dissolves into a poem about how the small-scale transformations of the erotic must be harnessed by the political”); Heti’s in that of a restless bohemian seeker (“I am writing a play that is going to save the world. If it only saves three people, I will not be happy”); Lin’s in that of someone trying to reconcile his saturation in life online with real-world connections (his Paul in a squabble with his girlfriend: “Paul felt himself trying to interpret the situation, as if there was a problem to be solved, but there didn’t seem to be anything, or maybe there was, but he was three or four skill sets away from comprehension, like an amoeba trying to create a personal webpage using CSS.”).

Persona and style merge in these books, and social and romantic conflicts align with the challenges of artistic creation. The specters of fraudulence and narcissism loom (Heti openly asks whether she and her friends should be like celebrities or reality-TV stars), and the book itself is what’s been brought forth to vanquish them. A curious feedback loop inscribes the reader’s experience of the text as an element, perhaps the ultimate element, of the plot. No coincidence, then, that criticisms of these books home in on the central personas (their lifestyles, politics, and morality). Or that several of these authors’ public appearances attract fans who, à la Holden Caulfield, “wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City shares much in common with these books, but he stops short of making his narrator, Julius, a writer. He’s instead a psychiatry student, and speaks in that profession’s terms: “Perhaps this is what we mean by sanity: that, whatever our self-admitted eccentricities might be, we are not the villains of our own stories.” But as Julius learns, he is the villain of someone else’s story: a friend from his teenage years tells him of the time he raped her — a story he can’t bring himself to tell us whether he believes or not. In other words, Julius may be a different sort of fraud: a moral fraud, and a criminal. Cole here shows the limits of autofiction: chronicling the lives of well-educated middle-class writers, it has little place for violence. In Lerner’s books it arrives in the form of a terrorist attack, a fatal accident a continent away, a hurricane, a potentially fatal heart condition; in Heti’s it’s sublimated into an explosive sexual affair; in Lin’s into narcotic derangement; in Offill’s into bedbugs.

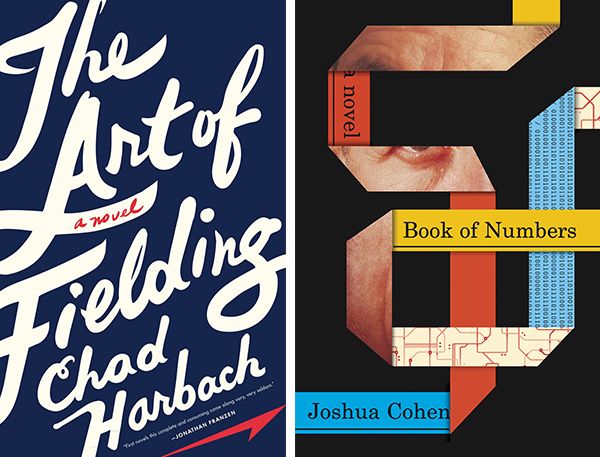

Any artistic movement worth its salt will spawn cousins (a parody strain of autofiction can be found in Tom McCarthy’s systems novel Satin Island, Joshua Cohen’s metafictional thriller Book of Numbers, and Ben Metcalf’s neo-Sternean tirade Against the Country) and encounter foreign allies. Of course, the Norwegian Karl Ove Knausgaard, with his six-volume My Struggle, is the European avatar of autofiction, the blur between himself and his hero of little dispute beyond the capacity of his memory. A consequence of this was tabloid scandal in Norway, the threat of lawsuits, and the changing of many family names after an early manuscript was circulated. At the same time, a generalized anxiety about authorship animated the mini moral panic and popular backlash against the alleged outing of Elena Ferrante as the translator Anita Raja. A resident of Rome since age 3, Raja’s background doesn’t match those of the characters in her Neapolitan tetralogy, nor that of the fictional persona Ferrante adopted in many interviews. Readers wanted the latter fiction to remain intact, lest it distract from the pleasures of the former. Who would be happy to learn that Cormac McCarthy had never left his birthplace in Rhode Island?

2. Degreelash: The New Meritocracy Novel

What if you were told that a brilliant author had never been to school? Her books would presumably acquire an aura of the authentic that marks the genius of the autodidact. But these days, everyone’s been to school, and most writers we read have been to graduate school, often very fancy and expensive ones. Most of them teach at such places, and the campus and its ideologies creep into their work. Put a nation of writers in a cage, call it a university, and they’ll start writing about their cage.

The cage used to be different. The word meritocracy was coined by Michael Young in his 1958 novel The Rise of the Meritocracy, a dystopian mock sociological treatise set a few decades hence in which a rigidly entrenched credentialed elite faces a revolt from below. (Sound familiar?) The first campus novels portrayed college as an asylum for eccentrics (Randall Jarrell’s Pictures from an Institution, 1954), or a launching pad for the children of a narrow privileged class (Mary McCarthy’s The Group, 1963). In today’s fables of meritocracy, the scholarship student is the default hero or heroine and institutions of higher education are sites of cultural and class intermingling imbued with a quasi-sacred power that used to attach to religion. Consequently, these books often dramatize a loss of faith.

The university in these books is a site of self-perfection but also a place of denaturing. The true self may be discovered at school, as in traditional campus novels, but often at the cost of shedding an accent and other vestiges of a provincial upbringing, which together make up another true self (this is also, more or less, the plot of Dreams From My Father). In these visions of meritocracy, authenticity is traded off or erased, depending on your faith in the system. True believers graduate with a sense that the system is fair and everybody gets what they deserve, especially when they tend to get everything they want. The disillusioned come away thinking they’ve been ripped off, stripped of their innocence and idealism, taught a stale philosophical argot, and expelled into a corrupt world they’re too confused to make their way through. Most often, these books follow talented individuals as they come up against the limits of meritocracy. That’s the howl you hear when the hero of Jonathan Safran Foer’s Here I Am screams, “Unfair! Unfair! Unfair!” in the face of a divorce and a cancer scare — two problems you can’t test your way out of.

Foer’s novel tells the story of uncoupling adults convinced of their own merit and their children’s “ethical and lucrative” futures. The pair are far from their college days but still under the system’s spell. (It also partakes of some of the tropes of autofiction: in an interview, Foer said, “It’s not my life, but it’s me.”) Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding examines meritocracy’s myths on the campus of a small Wisconsin college and with a keener sense that nothing is ever really fair. Its central allegory is a scholarship shortstop’s sudden loss of the ability to make accurate put-out throws to first base. The errant throw is an apt image for a system that rewards talent in action but withholds its favor from the average or deficient.

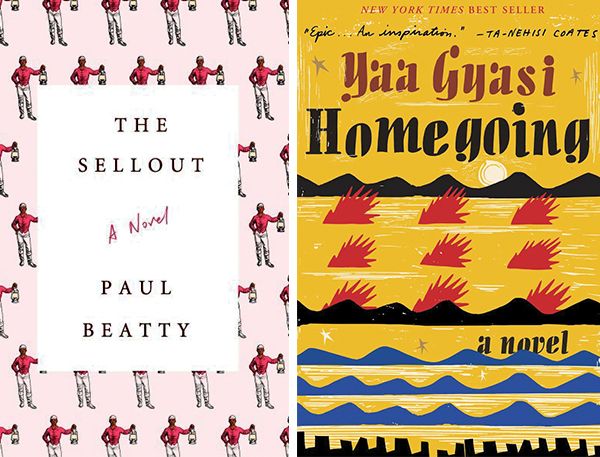

Perhaps none of these fables enacts the paradoxes of meritocracy and authenticity as straightforwardly as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2013 Americanah. Its heroine, Ifemelu, makes her way from Lagos through the U.S. higher-education system and back. In college and graduate school, she thrives and becomes a blogger indexing American class and race relations. There’s a tension in the novel between a belief in the socially ameliorative aspects of meritocracy (given sacred qualities on the first page: “Princeton, in the summer, smelled of nothing,” a quality absent in cities and even more pleasant than its “quiet, abiding air of earned grace”) and its failure to mend broader national and global injustices of race, sex, and class. With her American boyfriend, Ifemelu shares a mutual reverence for Obama, but he isn’t going to solve everything either. On returning to Nigeria, Ifemelu finds herself bored at her magazine job and not entirely satisfied with her homecoming, but her nostalgia for America has a limit. She doesn’t want to raise American children. “I don’t want a child who feeds on praise and expects a star for effort and talks back to adults in the name of self-expression. Is that terribly conservative?”

Adichie isn’t the only writer operating in a Victorian vein or giving voice to doubt to general skepticism that any of our systems always deliver anything like what they promise. In the Brooklyn milieu of Ivy League and Oberlin-ish grads in Adelle Waldman’s The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. the question is whether a durable relationship in a free romantic market can be made strictly on the basis of intellectual résumés. It’s one part Austen, one part Houellebecq. Nate, a writer about to publish his first novel, and Hannah — a thirtyish writer with a name pointing both to Arendt and Horvath — spend the novel finding out that being good on paper isn’t enough: physical attraction and emotional compatibility win the day. A sexy body turns out to be sexier than a Slate byline. It’s a sign of meritocracy’s deep ideological hold on a slice of the culture that such a turn could ever figure as a revelation, not so much for Waldman as for her audience.

As the critic Nicholas Dames has argued, a cohort of writers have adopted a realist mode while incorporating an element of their educations that had as one of its missions tearing realism down: literary theory. When they turn their attention to the system that equipped them to deconstruct the world, the result is acid satire. Their characters suffer crack-ups. Sam Lipsyte’s The Ask (narrated by a failed painter with a dead-end development job at “Mediocre University at New York City”), Nell Zink’s Mislaid (the story of a disastrous faculty-student marriage and its aftermath), and Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens (about the humbling quarter-life crises of a quartet of Stanford grads) all take up themes of fraudulence (false identities, the “fake internet,” the faux-ness of the hipster) and failure through the prism of theorized farce. In a neat paradox portrayed throughout these books, in a world where everything is on some level fraudulent, nothing is more authentic than failure itself.

3. Underworlds: The Retro Novel

American middle-class life circa 2008–16 — success or failure, it’s hard to escape the feeling that we’ve been living through a stale time. History is out there, transpiring, but it’s something you hear about on NPR or glean from glancing at tweets. You spend a lot of time looking at screens, working, but in all likelihood streaming films and television shows. So many costume dramas! Set just a few decades ago! The recent past was so much more romantic and better dressed! The terrorists were well-off white kids, and there were no computers!

The 1960s and ’70s have only just become available to historical novelists. They are all operating in the shadows of Don DeLillo’s Underworld (1997), with its postwar sweep, and of Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives (1998), with its center of gravity in the Mexico City of 1975. But DeLillo and Bolaño lived through that history. For Gen X and the millennials, the period has a different valence: It’s an era that’s never stopped dominating our television and movie screens or the pop-music landscape. It’s also an era we’ve been taught to romanticize as more dangerous, more fertile, and more authentic than the present. There was a true bohemia — in hippie and punk forms — and a genuine hedonism, before the baby-boomers turned to junk bonds and step aerobics. The Wasp ruling class was in decline, and the multicultural and feminist forces shaping the way we talk about the present were just emerging. The hold of corporate systems on America wasn’t yet complete. You could live in the city without leaving a trace, and spontaneous self-reinvention never stopped being possible.

The purest example of this sort of nostalgia is Garth Risk Hallberg’s 2015 novel City on Fire, a 927-page epic built around the 1977 New York City blackout. (Its nearest rival in epicness is Nathan Hill’s 2016 doorstopper on the 1968 Chicago riots, The Nix.) Another recent downtown 1970s novel, Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers, focuses specifically on still-pressing ideas about authenticity in art. One character, a performance artist and Factory habitué, stages her performance as a waitress by actually taking a job as a waitress in a diner:

“I had a strange feeling, like I’d decided to go over a waterfall in a barrel. I rented an apartment nearby, a studio with a Murphy bed. It was over an old shoe-repair shop. Neon blinked into my window all night long, startling me from sleep. At first I thought I would hate the neon, but I began to like it, the way it lent this air of tragedy to my so-called life, my performance as a waitress, neon flashing into the room, making me feel as if I were living inside a film about a lonely woman who threw her life away to work in a diner. And I was that woman! But the whole thing was in quotes.”

There’s no suppressing the present’s desire to have its way with the past, and from here its shadow will pass into the 1980s and 1990s, as writers will always first of all go about the business of revising the story of their parents’ prime. (They tend to start the job earlier these days; American writers of an earlier generation tended to wait until mid-career before turning to the historical novel; it’s also a form with a high potential for popularity and a commensurate potential for publishing paydays.) But there’s one reason the 1960s and ’70s will always exert a permanent obsession: they were the last days when most novels were written on typewriters and most phones had dials.

4. A Universe of Pain: The Trauma Novel

It would be nice to think that some experiences transcend time and place, but the way we talk about things that never stop happening is always subject to the conventions and tastes of the present. A character in Alice Munro’s last collection of stories, Dear Life, explains something about all of Munro’s work when she says that in her youth, sex and cancer were things that couldn’t be spoken about. They came to form the core of Munro’s themes, along with the experience of child abuse. Many of her stories link the experience of a childhood trauma to present-action adulthood, a structure that has set a blueprint for what the Wall Street Journal critic Sam Sacks has called “agony novels”: fictions that draw their animating force from a traumatic experience. Like sex and cancer, the way we talk about trauma has changed in recent years: It’s moved into the center and to the top of our hierarchy of the authentic, “a culture,” in Daniel Mendelsohn’s phrase, “where victimhood has become a claim to status.”

An exquisitely artful trauma narrative from 2016 could also be called autofiction: Garth Greenwell’s first novel, What Belongs to You, narrated in an incandescent monologue by a young American living in Bulgaria. Another — a more conventional work of literary realism, though its narrator is also a writer who invites some identification with the author — is the best seller My Name Is Lucy Barton, by Elizabeth Strout. In both novels, the traumas are acts of abuse and neglect by homophobic parents recalled by their children in adulthood. In Strout’s book, the abuse acts as a sort of psychological key that unlocks the emotional mysteries that have been hanging over a mother and daughter, reunited after years of estrangement at the daughter’s sickbed. In the story of Greenwell’s unnamed narrator, the memory of abuse at the hands of his father radiates across present events without providing any simple answers. These two strategies of presenting trauma have radically different implications for the larger narratives in which the traumas are embedded. When trauma is the key that unlocks the story, everything else becomes subordinate to the traumatic experience. If the trauma is radiant, rather than occupying a cause-and-effect relationship to the rest of the action, readers are left to make their own determinations of the trauma’s meaning. In the key model, trauma threatens to overwhelm the story. Radiant trauma leaves the novel room to move.

Two of the most celebrated novels of the past three years both present trauma as the trigger of a cycle that’s impossible to escape. Atticus Lish’s 2014 Preparation for the Next Life is told in a concrete, realist style that mostly eschews psychology. The doomed love story of an undocumented Uighur immigrant and an American combat veteran, the novel is set on the rough edges of Queens and grounded in the Patriot Act and the Iraq War — the springs from which traumas of rape, incarceration, and bloody episodes abroad and in America come. Lish himself is a Marine veteran and taught English in Central Asia. The gilded blocks of Manhattan and Brooklyn so much more common in contemporary American fiction seem a world away.

That world and its luxuries are the backdrop of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life (2015), but her novel’s hero Jude is eventually revealed to have a backstory of horrific child abuse. The novel poses a conceptual question: Can high achievement (Jude is a corporate lawyer), material satisfaction (wealth and choice real estate), and personal comforts (a loving circle of friends and a glamorous and loyal partner) compensate for the sufferings of serial pedophilia, which has left him disabled and prone to self-harm? The novel’s answer is no, and of course the deck is stacked from the start. A Little Life elicited a rapturous response from some reviewers (as well as National Book Award and Booker Prize nominations) and infuriation from others (including Mendelsohn and myself). And any book generating such vehemently split reactions must be doing something right. In Yanagihara’s case, it’s the combination of a realist chronicle of the high life — familiar to us from the lifestyle pages but always begging for novelization — and a gothic narrative (a distant and elaborate descendant of Poe) that puts to page the worst things we can imagine, the sorts of horrors that are generally consigned to horror fiction.

And what horrors we may be in for come January 20. Environmental despoliation, economic regression, and enthroned sexism and bigotry are already on the cards. For all the turmoil on our streets and abroad, literary historians may look back at the Obama years as a time of tranquility — when American writers had the luxury of looking inward, investigating the systems that formed them, reimagining the romantic days just past, and registering the echoes of personal traumas. It isn’t pretty to think of what’s to come.

*A version of this article appears in the January 9, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.