Not every show is good at onscreen texting, and even the good ones trip up once in a while. Texting is particularly awkward, in aesthetic and implementation, on The Mindy Project. On Jane the Virgin, Jane somehow still has the keyboard click sounds activated on her phone, which would suggest that she’s a variety of monster that the show has given us no other evidence to support. There are countless close-but-not-quite phone operating systems that will happily distract you with their unrealistic layouts and implausible notifications. And any aesthetic or device will quickly become a way to date a TV show, making it that much harder for audiences to become immersed in the fictional world even a few years after the show gets made. (Remember when Rory got a Sidekick? Veronica Mars had one too; those things were pretty cool, apparently).

In the age of modern romantic comedies, though, texting has been more of a boon than you’d think. Oh sure, you can quibble about whether someone’s emoji looks weird, and it’s taken a while for writers and directors to figure out the best uses of texting as both onscreen images and structural devices. When it works, though, good texting has become an incredibly useful way to tell stories, especially stories about love and relationships.

What are people thinking?

One of the trickiest things about telling visual stories — movies and TV alike — is how exactly you dramatize what’s going on in someone else’s head. Oh sure, you can rely on the staid and often incredibly dumb voice-over trope. You can use the language of cinematic storytelling to suggest things about what a character thinks and feels, using ever-popular devices like the close-up, the montage, the musical cue. Usually, TV and movies are usually stuck with exteriority.

Enter the text, which is not a perfect, all-encompassing solution, but does offer some intriguing possibilities for glimpses inside what a character’s thinking at any given time. My favorite of these is the onscreen edited text message, where we watch a character type, delete, and then retype something else. It’s even better when you get a visual of both sides of the conversation — on Jane the Virgin, you watch Rafael type “I love you,” delete it, and then end up sending a bland response. It’s intercut with shots of Jane, who watches Raf texting her with the three telltale iMessage bubbles, and who never sees the unsent “I love you.”

The unknowability of someone else’s mind is one of the deepest frustrations (and reliefs) of being a person, and it’s one of fiction’s strongest appeals, especially in a romantic-comedy genre. We get to know he loves her, even if she doesn’t yet. It’s awkward to watch a character write and then cross out the words “I love you” — it’s stilted and unusual. We can watch a character say “I love you,” but again, we’re confronted with having to look at their face and wonder what they really feel. The text message edit is more immediate, intimate, and casual than those. And we, the audience, get that delicious voyeuristic frisson of peeking into someone’s mind.

New rules and how to break them.

There are many delightful things about watching historical romances, including the costumes, giant estate houses, carriage rides, and that one inevitable group dance scene where everyone does a gavotte and the protagonists send each other smoldering glances. One of the chief appeals, though, is the sense that there are rules and set expectations for how exactly a courtship works: chaperones, calling hours, and, of course, correspondence.

In life, those rules were likely as ambiguous as any similarly universal dating rules feel now. If you got a letter from a suitor, it’s probable you put in effort analyzing it and wondering how quickly to respond, just as you would with a text today. But texting has given TV a way to create a new, familiar set of dramatic (and often comedic) scenarios out of the confusing, emotionally fraught mess of love and relationships. The number of TV characters who send texts and are ghosted in return — or who do the ghosting — has gone up dramatically in the last several years. The tension around the season finale of Younger hinges on Liza frantically trying to text her boyfriend Josh to talk things out, and his complete communication blackout in response. The question of how long to wait after responding to a text pops up on shows like The Mindy Project and New Girl.

Maybe the best example of this is a show like Master of None, which has an entire episode that dramatizes Dev’s struggle to negotiate a complex and delicate multiplayer text situation surrounding an open concert ticket and several women he’s potentially interested in dating. (His friend Arnold’s suggestion for how to break through a texting freeze is to send a picture a turtle crawling out of a briefcase.) When it’s done well, texting becomes a handily universal language for how to illustrate tension and shifts in a character’s love life, especially when the romance teeters back and forth between drama (the breakup text, ghosting, the evidence-of-cheating text) and comedy (the inscrutable emoji, the sext sent to the wrong person).

Scenes can grow and shrink easily.

The exact thing that makes texting so occasionally frustrating in real life – the knowledge that you do not have someone’s full attention, the awareness that you’re with someone in real life and would really rather just be paying attention to your phone – is a huge boon to romantic comedy dramatics. In particular, texting has a way of letting a scene between two people weave in other voices and other perspectives, and of dramatizing that expansion.

Take what is now a familiar kind of scene from Younger: Kelsey’s on a first date with someone she met on a dating app, and she wants to make sure she has an out in case the date is terrible. So Liza texts her shortly into the meal, offering Kelsey an excuse for leaving. The same thing happens to her date, who gets multiple check-in texts from his friend to give him an out. It’s a perfect romantic comedy setup — two people sitting together at a table, being interrupted by outside voices in a way that’s lightly funny. Their phones keep buzzing; they can’t even really speak to one another. And then it easily, readily tips into gentle romance when they make a mutual decision to turn off their phones. Two people (romance) moves to four people (comedy) and then back to romance again.

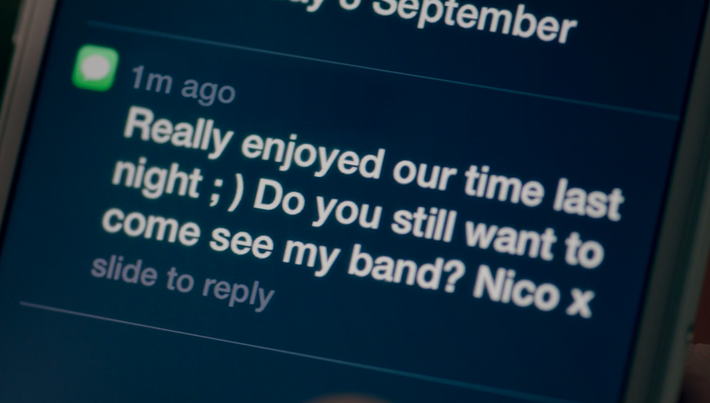

It’s also an ideal way to introduce the tension side of any romantic story — what better way to represent the conflict of a love triangle than two people in a room together, with one person receiving text messages from a third character? Take the final moments from season two of Catastrophe, as Sharon and Rob are finally reconciled and happily eating pizza together. Sharon gets a text from Nico, a guy she has no memory of possibly sleeping with the night before. Texting becomes a way to quickly and smoothly introduce characters and information into a scene, and the cell phone becomes a convenient, compact ticking narrative time bomb.

Whenever technologies of communication change, the language around how people fall in love changes, too. And so, inevitably, do the stories we tell about romance. In the 18th century, rising literacy rates and an increasingly robust postal system led to the popularity of the epistolary novel. Radio dramas had to figure out how to tell love stories almost entirely through direct dialogue and sound effects. You’ve Got Mail is the most infamous leap into digital courtship. In the era of the modern rom-com, texting has proven to be a surprisingly useful narrative device for stories about love, hooking up, and maintaining relationships. Even though everyone still leaves the damn keyboard click sounds on.