Raoul Peck’s driving, free-form documentary I Am Not Your Negro is not a direct response to Donald Trump’s delighted recognition of the lone nonwhite face he saw at one of his rallies: “Look at my African-American over here!” But the movie feels, if anything, even timelier, which is to say, timeless. It’s a translation of James Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript about Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr., Remember This House, with the text read by Samuel L. Jackson and footage of Baldwin giving talks and as a guest on The Dick Cavett Show.

This is Baldwin at his most polemical, but beneath his rage you can discern a groping for unity. He insists he “never really managed to hate white people.” It was, after all, a white teacher who opened his mind to history and philosophy. What he hates is being treated as if his anger is inappropriate and, worse, an impediment to black progress. He is ever amazed that whites don’t understand why he might not feel quite at home in a country that enslaved, lynched, segregated, and propagandized against nonwhites — and that still segregates and murders and, to use his own word, castrates them. Even at its friendliest, the culture still condescends to the Negro — though he doesn’t actually say “Negro.” He says, “I am not your nigger.”

It’s the propaganda that irks him most, the betrayal of the imagination. Baldwin has predictable issues with John Wayne, but the squeaky-clean Gary Cooper puts the most deceptive face on the killing of Indians. If you’re black, Baldwin says, you identify with Coop until you realize that the Indians are you, and that Coop, and Wayne, is a symptom of a culture that won’t “grow up” and face a history that has “no moral justification.” It’s “the lie of pretended humanism.” It’s Coop and it’s — wait for it — Doris Day.

I admit my hackles rose when Peck cut to Day in some vapid comedy. She’s now very old and very nice, an animal-rights activist and someone who sang with black jazz musicians before — as Oscar Levant put it — she was a virgin. Does she deserve the crosscutting between The Pajama Game and images of whites posing under black bodies hanging in trees? Yes, I’m defending a white woman’s honor, and yes, that feels weird. On the other hand, it’s useful to understand what Doris Day symbolized in the ’50s and ’60s while blacks were being brutalized. Only whites were surprised by Birmingham, says Baldwin.

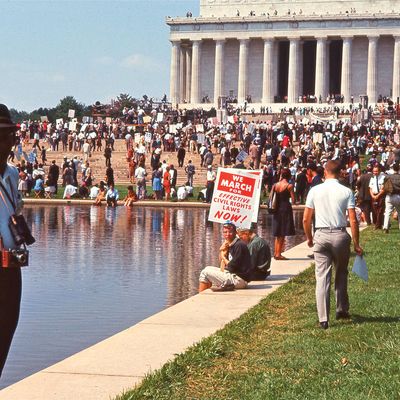

Along the way, Baldwin speaks cogently — though not especially vividly — of Medgar and Malcolm and Martin, as well as of Lorraine Hansberry, who smoked three packs a day and died at 34 of pancreatic cancer but was, to Baldwin, a victim of her fierce struggle for equality. The black-and-white archival footage feels intimate. And if the time line of I Am Not Your Negro is muddled, that’s by design: Peck’s loose structure allows him to skip to the present — to footage of Ferguson and photos of young black men slain by police in the last five years — with no loss of continuity. It can be argued that the interpolations are opportunistic. I suspect Baldwin would say that they’re not just Peck’s right but his duty.

Throughout I Am Not Your Negro, I had the urge to temper Baldwin’s hyperbole. The impulse was snuffed out when, in a 1968 clip from The Dick Cavett Show, the host brings on the philosopher Paul Weiss, who says Baldwin is making too much of race — that he and Baldwin share a universal experience of the world. The task of life, he says, is to “become a man, blah blah blah” — whereupon Baldwin interrupts to say that “becoming a man” can get a black man killed. He has never seen in American institutions the idealism of which Weiss speaks. The scene reminded me of David Brooks’s attempt to counsel Ta-Nehisi Coates (in regard to Coates’s Between the World and Me) not to be so … categorical. The reaction wasn’t pretty.

Here’s an example of Baldwin’s nervy refusal to be anyone’s Negro. Some people, he tells an audience, think that “in 40 years in America we might have a Negro president.” Move over, Nostradamus! But he translates this as: “In 40 years if you’re good we may let you become president.” Baldwin goes on, “I am not a ward of America … I am one of the people who built the country.” If he’d seen the abuse heaped on a painfully conciliatory figure like Barack Obama, he’d probably think we were in worse shape than we were in the ’60s.

*This article appears in the January 23, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.