It might be possible to enjoy the musical Big River by squinting. It is, after all, based on Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, whose main events — Huck’s escape from his Pap, Jim’s escape from slavery — are neatly miniaturized in William Hauptman’s stage adaptation. Seventeen pleasant American vernacular songs by Roger Miller (“King of the Road”) aptly reference country, bluegrass, gospel, and rockabilly. (There’s plenty of fiddling from the orchestra, which also features harmonica and Jew’s harp.) Now even more than when it first appeared on Broadway in 1985, its overall feel-good sentiment about the possibility of happy endings to the story of race in America would seem to be welcome. And yet if you are even a little bit alert to the questions raised in the intervening 32 years about tokenism and cultural appropriation, you will not be able to watch Big River without squirming. It has approximately the same moral seriousness about race as a lawn jockey does.

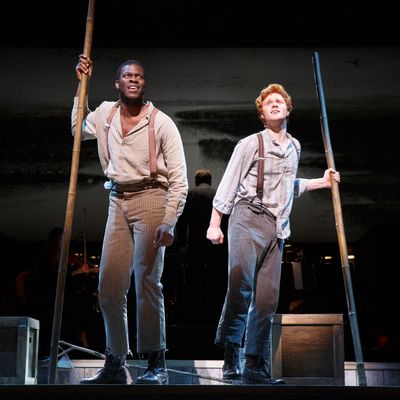

Which is not to argue with the Encores! series for choosing to produce it as the first show of its 24th season. Examining vintage musicals that may not be revivable on Broadway today (though Big River is frequently produced in the amateur market) is basically the Encores! mission. And the production itself, directed very simply by Lear deBessonet, is modest enough to avoid making too big a case for the show’s enduring worthiness. DeBessonet, who created the terrific, communitarian Public Works program at the Public Theater, stages the story fluidly on a simple set (by Allen Moyer) of worn wood platforms with a period engraving of the broad Mississippi behind them. Especially at the beginning, she tones down the performative exuberance to such an extent that Twain’s linguistic verve seems to be coming at you through the haze of a coma. I’m not sure what her Huck Finn — bright-redhead Nicholas Barasch, recently of She Loves Me — is playing, with his languor bordering on affectlessness: Are we meant to see Huck as the traumatized victim of Pap’s abuse? It’s only his escapade with runaway Jim (Kyle Scatliffe, recently of The Color Purple) and the rowdy characters that their rafting adventure throws at them that begin to wake him up. DeBessonet finally disengages the mute button when those scoundrels, the fake Duke of Bridgewater and the “Dolphin” of France (Christopher Sieber and David Pittu, both grand), arrive at the end of the first act.

But Twain was not writing about Huck’s awakening to fun. It was the moral awakening of the country to the sin of slavery that interested him, an awakening he traced in Huck’s changing attitude toward Jim. Well into the narrative, Huck still considers his adventures with Jim a lark, a vacation from the pressures of his own alternately sanctimonious and abusive adults. Jim’s humanity, let alone his equality, is only intermittently clear to him, like a distant signal, perhaps from the future. (He keeps forgetting that the man has a wife and children.) And though Twain wrote the novel some 40 to 50 years after the events he describes — some of them based on stories he’d heard and people he’d encountered — he is not so sanguine about himself or America as to suggest that the problem had been solved by the time of composition, let alone by the end of the novel. Not for nothing is Huck, his symbol for the country, a rambunctious, barely educated 13-year-old. He has merely bumbled his way into an approximation of morality; Jim’s emancipation is not, after all, his doing. The prissy Widow Douglas frees him in her will.

All of this is duly noted in Big River but barely dramatized. What the authors seem to have found sufficient is to hang the facts like flaglets on a string while focusing all of their energy on entertainment. Other than Jim, whom Scatliffe renders with the expected dignity and beautiful voice but cannot fully round, the black characters are entirely undifferentiated and unattached to the plot. I found it mortifying each time they were trooped out to sing, however lovely the song; perhaps it is a bit of theatrical authenticity that Big River harks back to the Civil War–era minstrel shows that Twain himself enjoyed. But showmanship does not excuse the fact that the authors treat Jim exactly as Huck and the others do: That is, they mostly ignore him, even leaving him in chains on the raft, until they need him. It’s not his drama, and that’s the problem.

I’m not saying that a story about white people’s awakening to the immorality of slavery doesn’t deserve to be told. But in 2017 you can’t use a chorus line of slaves just to decorate that story with unmoored testifying and gospel thrills. Exploring the difficulty — there are other difficulties, too, but they pale by comparison — would be a perfectly good excuse for mounting Big River at Encores! Unfortunately, it is beyond the series’ brief to undermine what it examines. It is left to a program note to supply the crucial information that Neriam Todd, the character upon whom Twain partly based Jim, never made it to freedom, by raft or by will. He was killed by woodsmen on the island where he was hiding. Later, the 11-year-old Samuel Clemens came upon his corpse. The boy fled in horror; still, despite the warning appended to the novel (and the musical) that “Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot,” that horror informed every moment of the entertainment that was Twain’s masterpiece. The authors of Big River were not so impressionable, not so finicky. Nor, apparently, are we.

Big River is at City Center through February 12.