Of the many comfortable forms of pop culture available to you in recent months, one of my favorites involves watching Neil Patrick Harris pretend to be a sailor, badly. In the fifth and sixth episodes of Netflix’s Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, Harris plays Captain Sham, a lonesome sailor who’s looking for love with Alfre Woodard’s neurotic Aunt Josephine. Of course, as is obvious to both the audience and the show’s protagonists, the Baudelaire children, Captain Sham is really the nefarious Count Olaf in disguise, following them so he can get his hands on their fortune. Sham often seems to have a Sean Connery–esque brogue. He doesn’t know anything about boats. It’s all so very obvious, but the adults never notice.

In the Series of Unfortunate Events series, as in the books and not-so-great 2004 film, most of the world is a big sham. After the Baudelaire children’s parents die in a fire, in each new chapter of the story (which equates to two episodes of the show) they’re sent to live with a new relative who is totally oblivious to Olaf’s painfully obvious new disguise. They eventually unmask him, escape, and the cycle continues once again. The fun along the way comes from the story’s off-kilter sensibility, seen in the narration, provided by Patrick Warburton, who pops up with his melancholy baritone to provide exposition and define a word or two, the surreal production design (a marriage of Barry Sonnenfeld and Bo Welch), and Harris’s on-the-nose performance. While playing Olaf and his many alter egos, Harris is hammy, obvious, and a little annoying. It ends up being the right choice.

As a character, Count Olaf is hard to reconcile, at once farcical and terrifying. In the 2004 film, Jim Carrey took every part of Olaf to broad extremes. Wisely, in the Netflix show, Harris’s Olaf has more contradictions. His malevolence is closer to the surface, but his motivations are more hidden. He’s in it for the sake of money, supposedly, but also revenge against the Baudelaire family. Mostly — and this is what Harris’s performance emphasizes — it’s because Count Olaf thinks being evil is fun.

What makes it so fun is that Count Olaf’s brand of evil is a big, obvious performance. Harris is a showman (author Daniel Handler mentioned that he loved Harris’s hosting work at the Tony’s), and he leans into the idea that what Count Olaf loves, above all things, is a good show. In “The Bad Beginning,” he goes from performing a musical number about his very evilness to slapping Klaus at a dinner table. In “Miserable Mill,” he pops up in drag pretending to be a ditzy assistant, dropping his pen for an exaggerated bend-and-snap that is somehow more obvious anything Elle Woods ever attempted in Legally Blonde.

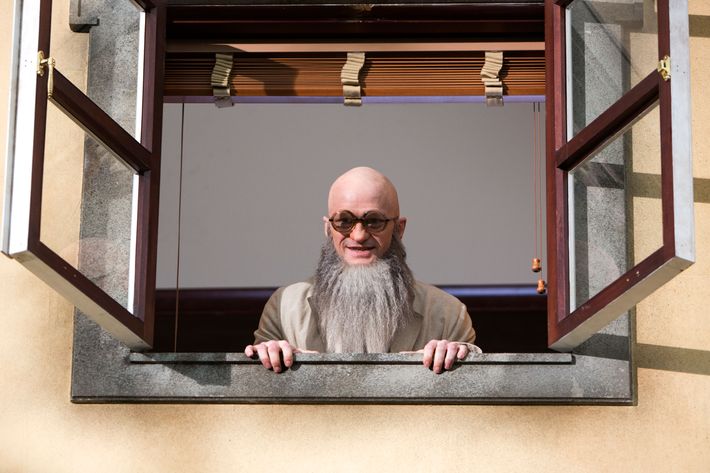

In part, Olaf’s hamminess is just there for humor. Lemony Snicket is a kids’ show and kids love kooky disguises — a weird sea captain? Great! A reptilian assistant with giant glasses? Without a few spoonfuls of levity, this would just be a show about helpless kids fleeing a psychopath who’s murdering their relatives one by one. But Olaf’s bad disguises, and his obvious acting, also makes the imbalance of power between himself and the Baudelaires all the more stark. In one episode, he decides to marry Violet by recruiting a real lawyer to perform a real wedding in the middle of a sham play. Evil loves an audience, and in a sinister way, the fact that it compels an audience reinforces its power. Think of supervillains monologuing in action movies, or in an unsettling real life example, Steve Bannon saying, “Dick Cheney. Darth Vader. Satan. That’s power.” In not hiding his nefarious plans — or at least not bothering to hide them very well — Count Olaf is bragging about how much he can get away with. None of the adults in Lemony Snicket want to believe that anything evil is happening, even if a villain like Count Olaf is right in front of them with an obvious fake beard.

The world, full as it is with complacent adults, might be rigged in Count Olaf’s favor, but luckily, the Baudelaire children aren’t fooled. Neither, of course, is the audience of the show. That’s the two-sided nature of Count Olaf’s bad acting: It’s unsettling to watch Olaf’s obvious disguises go undetected, but his performances also push the show into the comfortably absurd. The repetitive structure of Lemony Snicket wears on you as the plot moves forward — you know what’s going to happen as soon as the kids meet their next sucker of a guardian — but the variety of nonsense Harris brings to the screen keeps you engaged. Plus, watching a work of fiction, we have the comfort of identifying Olaf’s chicanery from a distance, even if other obvious liars are swindling us in real life.