When The Golden Girls debuted earlier this week on Hulu, scores of fans — most of us no doubt wearied by the constant worrying news out of Washington — turned to the streaming service in search of some comforting, familiar slut jokes and St. Olaf stories.

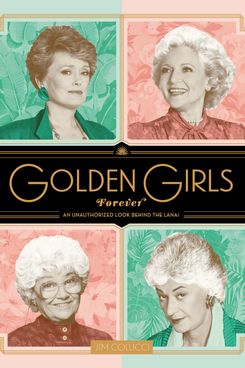

Even after having studied the show for a decade while writing my book, Golden Girls Forever, I still couldn’t resist some fresh viewings, as well. And once I tuned in, I was reminded of one of the things that had first made me want to invest so much time in heralding these four ladies from Miami; they were brilliantly, and sometimes even eerily, ahead of their time.

The Girls consistently tackled taboo subjects and found a way to make them funny. How the show accomplished the humor is now obvious; The Golden Girls was created by the legendary Susan Harris, and spawned the writing careers of so many of today’s TV comedy giants, including Desperate Housewives’ Marc Cherry, Arrested Development’s Mitchell Hurwitz and Modern Family’s Christopher Lloyd. But why did the show take somewhat of a risk in talking about sensitive topics?

The answer, as I learned from these writers and producers and three of the show’s brilliant stars, Bea Arthur, Betty White, and Rue McClanahan, was that the Girls were beloved not just for the barbs they’d trade, the outfits they’d work or the cheesecakes they’d share. These were four strong women who had lived through both the toughest and most rewarding parts of anyone’s life: having babies, struggling to stay afloat, losing husbands. Along the way, they’d gained not just wisdom, but also license with a TV audience to deliver shocking truths that a 30-something character couldn’t get away with saying on any other sitcom. And so, perhaps even a little bit selfishly, the Golden Girls writers realized early on that their show could have certain subject areas all to themselves.

In 22-minute increments over the course of seven seasons, the Girls raised issues of sexism and age discrimination as they faced off with chauvinistic plumbers, skeptical bosses and doubting doctors. They highlighted the plight of the homeless, and of elders like Sophia’s friend Lillian, receiving substandard and underfunded nursing-home care. They received their LGBT friends and relatives with open arms … well eventually, in the case of Blanche and her baby brother Clayton. When Sophia’s friend Martha wanted to end her life, they agonized over euthanasia; as Dorothy’s prized pupil faced deportation, they raised issues about our policies on immigration. And when Rose received a letter saying that she might have been exposed to the HIV virus, The Golden Girls capitalized on its political license once again, becoming one of the first sitcoms to mention HIV and AIDS at all, and further to suggest that the epidemic was a problem for everyone, not just the gay community.

In the Golden Girls Forever excerpt below, about the fifth-season episode “72 Hours,” writers Tracy Gamble and Richard Vaczy, stars Betty White and Rue McClanahan, and other members of the show’s crew talk about the making of the historic episode — one of the first, following an episode of CBS’ Designing Women, to bring humanity to the AIDS epidemic, and to bring that crisis to our attention in our living rooms.

“72 HOURS”

Written by: Richard Vaczy & Tracy Gamble

Directed by: Terry Hughes

Original airdate: February 17, 1990

Rose receives a letter from the hospital where she had her gallbladder removed warning that during her transfusion she might have been exposed to blood containing HIV antibodies. As the ladies accompany her to the hospital for an AIDS test, Blanche comforts a very frightened Rose by explaining that she too had the test and knows what her friend is going through. But after checking out fine physically, Rose is surprised to learn she must wait three days for the test results.

Unable to sleep, Rose begins to become hysterical, leading the ladies to realize how traumatic waiting for the results can be. They discuss times when they’ve had to wait and were afraid, then vow to help Rose through whatever comes along — even though, as Sophia points out, it’s scary when the disease is so close to home. The seventy-two hours finally over, the girls all breathe a sigh of relief as Rose finds out that she’s fine.

RICHARD VACZY: Tracy and I really loved the idea of showing what must that time be like between knowing something might be wrong and finding out what it is. And with the theater backgrounds of everyone on the show and the people they knew with HIV and AIDS, we thought everyone would appreciate and therefore love it. We guessed wrong. It turned out to be the darkest week I ever experienced on that stage, because the material hit so close to home.

BETTY WHITE: Not only were people understandably afraid of AIDS, but a lot of people wouldn’t even admit it existed. So this was a daring episode to do, and the writers went straight for it. It’s interesting that they picked Rose for that situation. Blanche was such a busy lady, but if it had been her story it would have taken on a whole other color. But with Rose being Miss Not-Always-With-It, it came as a real surprise.

DAVID A. GOODMAN: When Richard and Tracy were pitching the idea for this episode, I have to admit I didn’t really get it. Rose is going to have an AIDS test? I didn’t see how that could work. Now, of course, having had a career on Family Guy making AIDS jokes, I can’t really point a finger.

There was a running joke in the episode where Sophia would follow Rose around, washing everything she touched. Estelle, who was already a big AIDS activist, was not happy. She didn’t like the jokes, and so she really tanked them at the table read. In general, I remember that table read being very scary, because it didn’t score. And The Golden Girls was a show where otherwise, table reads had always gone very well.

RICK COPP: I was only twenty-four when I was hired on the show, a “baby writer.” I was semi-closeted — and I think part of the reason is that I was petrified about AIDS. This episode happened only a few years after Rock Hudson had died, and Elizabeth Taylor was among only a few people who were making a big effort to get the word out about the disease. There wasn’t a lot of information out there like there is now.

PETER D. BEYT (editor): It was while I was working on The Golden Girls when we found out my partner, Dean, was HIV positive. Estelle Getty was the first person I told. Her nephew was HIV positive, so she and I now had a connection. This was a new, scary world we both had to face. News stories would show the hospital room no one would go into, except in full hazmat suits. For six months, a family member — who works in infectious diseases — wouldn’t let me go near his children, because they didn’t yet know how HIV spread. It was a lot to go through. And when I would get to work, and be carrying all this baggage, Rue and Betty and Estelle, and occasionally Bea, were friends I could talk to.

Later on, I would start directing Golden Girls episodes. But when I was an editor, I would sit with the footage every Monday after tape night, and of course watch everything very closely and carefully. And I often felt like the episodes were really relevant to my life. In “Old Boyfriends,” Dorothy has a moment where she tells the dying woman, Sarah, “The only time you’re wasting is the time you and Marvin should be spending together.” That really hit home with me, and was one of the things that inspired me to take a year off to care for Dean. In a later episode, “Home Again, Rose,” which I directed, the Girls can’t get in to see Rose after her heart attack because they’re not immediate family; well, I’d just had the same experience with Dean, after he’d had a seizure in a restaurant.

But it was really “72 Hours” that for me showed what TV can do, and how far a sitcom can reach. I hadn’t gone to the taping of the episode, but I was set to edit it. I hadn’t read the script, and I had no idea what it was about, or what was coming. This was in early 1990, a time when there was still so much shame about the disease. Having grown up in Louisiana, I already was feeling shame about being gay. My partner was dying, and now I was ashamed about that, too, and feeling on some level like I deserved this.

So here I was, editing away, watching the episode for the first time. And I got to the point where there’s an argument between Rose and Blanche. I looked up at the screen in time for Blanche to say, “AIDS is not a bad person’s disease, Rose. It is not God punishing people for their sins!”

My heart stopped. All of a sudden, unexpectedly, here was this woman on a sitcom I was cutting, talking about what I was feeling. I always admired Rue as a star and a friend anyway, but now a character I’d come to know so well was saying what I needed to hear. I broke down, of course. I had to stop working. And then I pulled myself together — and from that point, right in the middle of my partner’s battle, I no longer thought I was a bad person. The show changed me in that moment of desperation. And my God, did the world ever need that to be said!

TRACY GAMBLE: This episode was based on a true story that had happened to my mother. She got notified that if you had had a transfusion in this certain period of time, you had to get checked. She and my dad were scared to death. It ended up fine, and she knew that the odds were against there being anything wrong. But it was hell to sweat out those seventy-two hours until she got the results.

My writing partner, Richard Vaczy, and I thought it would be a good storyline for Rose, partly because the audience might view her — and she views herself — as the last person who might have to worry about HIV. After all, she’s just a Goody-Two-Shoes from Minnesota. We also liked how with the four characters, everyone could have a different opinion about the subject, which would be a good way to raise issues we wanted to raise while still being entertaining. So, Rose had the common reaction of thinking, “I’ve never been bad — why did this happen to me?” She then lashes out and says to Blanche, “You must have gone to bed with hundreds of men. All I had was one innocent operation!” When Blanche responds, “Hey, wait a minute; are you saying this should be me and not you?” it raises questions of what is “good” and what is “bad,” and what does it matter, anyway? As Blanche reminds her that AIDS is not a bad person’s disease, she’s saying that just because I’m promiscuous, that doesn’t mean I’m a bad person.

Before we started writing, Richard and I talked to HIV experts at UCLA and asked what information they’d like us to put across. At that time, there was a cottage industry of testing centers where people could walk in, and then would call up days later for the results. And while it was good that people were getting tested, the UCLA people stressed that there needs to be counseling for people when they get their results, whether positive or negative. So we were happy that this episode became an opportunity to get the message out there that either way, people need support — which is what we have the doctor say to Rose when he says that she’s fine. In Rose’s case, she has the built-in support system of Dorothy, Blanche, and Sophia. They are the ones to help her make it through the three-day waiting period and all of the denial and panic. And they do it by letting her know that no matter what Rose’s test results might be, she is going to be okay because she is loved.

From the book Golden Girls Forever: An Unauthorized Look Behind the Lanai by Jim Colucci. Copyright © 2016 by Jim Colucci. Published on April 5, 2016, by Harper Design, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.