The Scarlett Johansson version of Ghost in the Shell is being released this Friday, whether we want it or not. It’s been notoriously tricky for Hollywood to successfully adapt anime and manga titles, even if they later get a critical reappraisal (see: Speed Racer, Edge of Tomorrow). But in the case of a classic franchise like Ghost in the Shell, which most American viewers know from the 1995 Mamoru Oshii film, there’s more of a known quantity to live up to — this is one of the most influential franchises in anime history.

Still, most American moviegoers have only seen Oshii’s film, if that, and Ghost in the Shell, like many anime franchises, exists over multiple films, TV series, and manga that were still going strong as recently as 2015. And the cyborg heroine Major Motoko Kusanagi has been reincarnated in multiple ages, temperaments, and bodies (or lack thereof). In other words, if ScarJo’s take flops, she won’t be the first Major that fans have accused of ruining the series.

The silver lining, of course, is that it’s an excellent excuse to dig into the heady world of Ghost in the Shell. Here’s a quick guide to the essentials to get you started.

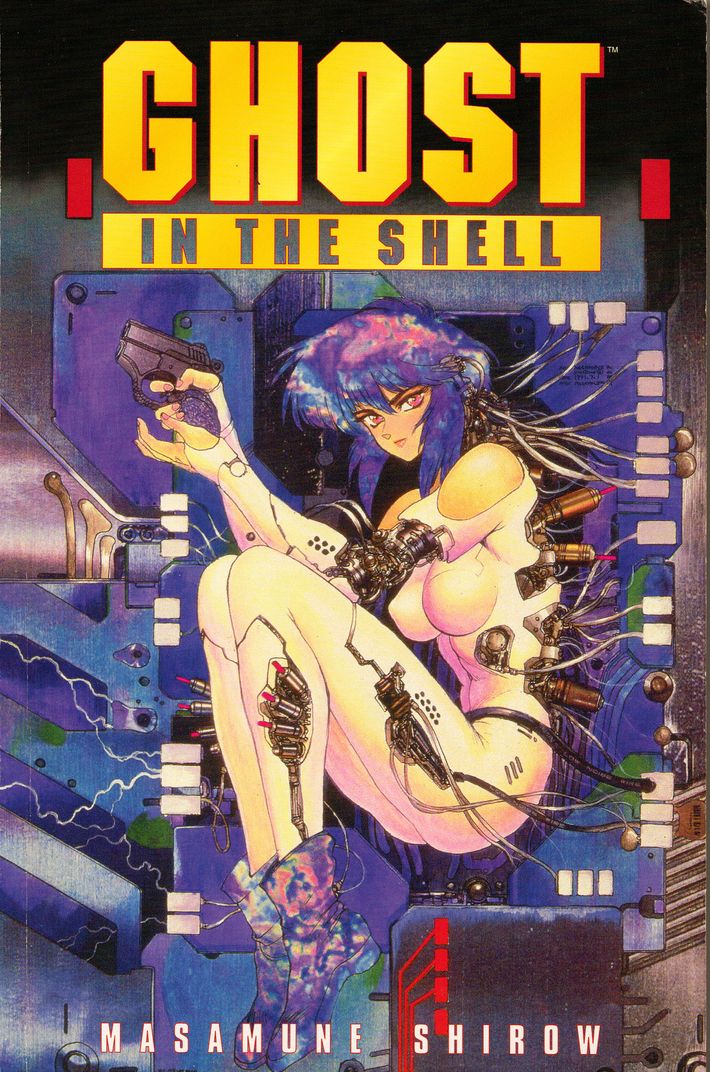

The Ghost in the Shell (1989), by Masamune Shirow

The manga that kicked off the franchise may surprise first-time readers already familiar with the anime, due to its lighter tone and depiction of the Major. The manga, after all, debuted in the late ’80s, before Japan fell into an extended recession, when the tech boom was still a source of gee-whiz inspiration for sci-fi comic authors and animators. Shirow’s first series follows the episodic adventures of the special-ops security force Section 9, headed by Major Motoko Kusanagi, a tomboyish tough-girl who happens to be 97 percent cyborg.

Shirow is responsible for the technical concepts of cyberbrains, prostheses, and ghost hacking, as well as the “Puppeteer” plot that would serve as the basis for the 1995 film. He writes copious idiosyncratic notes in the margins, fleshing out various ideas more thoroughly for whomever cares, and cracking jokes. He’s also a bit of a lech, and never saw a female character whose crotch he wouldn’t draw in loving close-up. It can be distracting in what is otherwise a densely conceived and entertaining sci-fi procedural. Still, “cute Motoko,” with her silly faces and easygoing fraternal relationship with her colleagues, is a fun variation on her more well-known anime counterpart, swilling beer with abandon, not yet affected by post-bubble ennui. Shirow followed the original series up with Ghost in the Shell 2: Man-Machine Interface in 1997.

Ghost in the Shell (1995), directed by Mamoru Oshii

Arguably the high point of the franchise, and certainly the most internationally known, Mamoru Oshii’s feature film adaptation took a subplot from Shirow’s manga and turned it into a meditation on consciousness and the philosophy of the self. It’s a bold direction to take with the source material, placing the Major on the brink of an existential crisis, and flipping the manga’s fetishization of her body on its head (but not getting rid of it, heavens, no).

The film’s brilliantly creative action sequences inspired Western filmmakers from the Wachowskis to Steven Spielberg to take note. But Oshii does a lot with character — making a more sensitive figure out of the Major’s cyborg partner Batou, and letting mostly biological Togusa act as a wide-eyed audience surrogate. The real supporting star, however, is the iconic, haunting score by Kenji Kawai, whose main theme elevates the virtuosic opening sequence and halfway-point montage of the city, which is plot-free and dialogue-free but vividly evokes Motoko’s alienation — from the society she lives, and even her own body. This is Ghost in the Shell at its moodiest, and perhaps incidentally, its most successful.

Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex (2002–2005), directed by Kenji Kamiyama

The Major and the crew at Section 9 returned for this alternate-timeline anime series headed by Kenji Kamiyama, who had previously worked on the Patlabor series with Oshii, among others. The series, which spans 52 episodes in total, is a procedural-serial hybrid. Some episodes, labeled “Stand Alone” in the first season, are just that — sci-fi one shots about various scenarios in the cybernetic world of Newport City. The rest are “Complex” episodes, part of an overarching plot — the first season focuses on the “Laughing Man” hacker and his many imitators, the second on a refugee uprising.

For many fans this is the definitive iteration of the franchise, fusing Shirow’s roving, speculative storytelling with Oshii’s more impressionistic, philosophical approach. The animation is a peak example of how to meld CGI and traditional animation — it’s deployed just enough to make those car chases more thrilling and those Fuchikomas more lifelike. The Major herself is not quite the sassy pinup of the manga, nor the haunted soul of the film, but a tough operator who can crack a joke now and then — and whose past is fleshed out in much more detail over multiple episodes. She exists as part of a colorful ensemble, with Togusa and Batou in particular getting more depth and story lines of their own. (There’s also a 2006 Stand Alone Complex movie, Solid State Society, also directed by Kamiyama.)

Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004), directed by Mamoru Oshii

Oshii returned to the franchise nearly a decade after the first film to explore another thread in Shirow’s manga, this one about illegally manufactured sex androids who start murdering their owners. Oshii, master of not giving the people what they want, sets this after the events of the first film, after the Major has (spoiler) fused herself to the Puppet Master and exists more or less full-time in the network. Batou takes the lead — which is great, because Batou is great — but Motoko’s absence is felt sharply, most of all by him.

The animation is a more ambitious CGI hybrid than Stand Alone Complex, and unfortunately, much of it has not aged well. (The CGI is mostly reserved for scenery and vehicles, while the characters remain hand-drawn, giving it a weird video-game feeling at times.) But it also lends itself to some of the film’s more unsettling moments — this is a scarier film than the first Ghost in the Shell, and a sadder one, too. When the Major does make her long-awaited entrance, Oshii intentionally makes it a sadly empty encounter.

Continued viewing: Arise, Sleepless Eye, Patlabor

The most recent iteration of the franchise is the 2015 prequel series Arise, which depicts a younger, post-adolescent Motoko meeting the team that would become Section 9 for the first time. It’s more or less based on the 2013 manga series Arise Sleepless Eye, and fan reaction has been mixed at best.

If, however, after an initial tour of the films and the manga, you sense that you’re more of an Oshii fan than a Shirow or Kamiyama fan, then I would recommend checking out the two Patlabor films that Oshii directed prior to his first foray into this franchise. His Ghost in the Shell is such an iconic post-bubble ’90s work, and it’s fascinating to see where his mind was with regard to Japan’s relationship to technology before the recession. Patlabor deals with many of the same themes of artificial intelligence, and has a deeply wonky fascination with infrastructure and politics, but it’s also a brighter, sunnier production with equally impressive animation and action sequences. Fans of Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell will find a lot to love here, including a very familiar and very atmospheric tour through another dilapidated shantytown in another hypermodern vision of urban Japan. It’s ghosts all the way down.