There was a time when America Ferrera considered leaving art for activism. She was 17 years old and had just been thrust into the national spotlight, after 2002’s Real Women Have Curves became the most-talked-about film at Sundance that year. September 11 had occurred a few months earlier, and Ferrera, then a senior in high school, was so shaken, she debated giving up on acting entirely to pursue a more humanitarian career. But what one of her professors at USC said stuck with her: Citing the impact Real Women had on another Latina student, he convinced Ferrera that art could be just as influential as activism. These days, the star and producer of Superstore is comfortable navigating both spaces, from acting in and directing this Thursday’s episode of her NBC sitcom to addressing a crowd of thousands at the Women’s March. On Saturday, she received a standing ovation when she accepted the Human Rights Campaign Ally for Equality Award for her work for the LGBTQ community.

In her acting career, Ferrera, 32, has never been afraid to take risks, whether stripping down to her underwear in Real Women or wearing a bad wig and fake braces, for four seasons, on Ugly Betty. But it’s taken her longer, and years of therapy, to shake her fear of failure in realms like director, activist, producer, she told Vulture recently at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. Sporting a 100% Human T-shirt, jeans, and a leather jacket, the Emmy winner was relaxed on a hotel couch, her legs tucked underneath her, as we discussed the problem with Latino narratives, why she struggled with her cultural identity for so long, and whether she’d ever run for office. (She answered like a born politician.)

On Superstore, you play Amy, a jaded employee at a big-box store. Your directorial debut on the show, “Mateo’s Last Day,” airs Thursday. Is this something you’d wanted to do for a while? Definitely. It was a conversation I had been having with our showrunner and creator, Justin Spitzer, and he was always incredibly supportive. I had such a wonderful time doing it and realized quickly that I have strong opinions, which I already knew in my life, I just didn’t know as a director. Turns out you’re just the same person! I’ve made over 100 hours of television by now and just realized there’s always going to be some level of fear and discomfort when you’re doing something you’ve never done before, and sitting around waiting for something to feel not scary would mean I’d probably be sitting around forever.

Did you get to pick which episode you directed?

No. It was all about schedule, because I had to be able to prep in a down week. So it was whatever episode was coming after the hiatus week.

It’s interesting because you had Mateo’s story about being undocumented. I thought, This is the perfect episode for you to direct.

I know; it’s funny [laughs]. It actually took me a while to realize, oh, I got the undocumented story, which I really believe was by chance. This is one of the things that drew me to this show: There is nothing really flashy in the hook of it other than it’s a show about everyday, working-class people, which is who I am, it’s what I come from. I am the daughter of two immigrants who worked several jobs to keep food on the table and the lights on. And by the way, we still found joy in life, we still loved people, and had relationships and breakups. So pointing the lens towards the everyman and bringing value to that experience was really intriguing to me because it’s something we’ve moved further away from. I would venture to say that it isn’t just in our film and television that we’ve ventured from that. We are living in a political climate that in a large way is a result of that — of so much of our culture shifting focus from the average experience of American life and more towards the extremes. And there is a small, silent revolution in pointing the camera at the common person who is not saving the world or the world’s best FBI agent, but who is just getting by and finding the humor and the love and the stakes and the victories and the tragedies in everyday life. It makes me very, very proud to be on a show that is confident enough to do what is seemingly not big and flashy in a landscape where you have to be big and flashy to stand out.

What was it like to direct and act at the same time?

I have to say, I didn’t love it. Being honest.

Do you wish you could have just directed?

Well, I did get to. For the first three days, I got to just direct, and I loved it. What I love about directing is very different from what I love about acting, and I couldn’t find a way to do both at the same time.

What do you mean?

What I love about acting is being super present and generous and discovering something in the moment. That demands a focus and a presence that is contrary to what I love about directing, which is, I love to hold the space, and I love to watch what’s happening and see it from the outside. Kudos to anyone who can do it and who enjoys doing it. For me, it was a lot harder than I even thought it would be.

Directing a TV episode has its own challenges because you’re working within the template of a show. You’re not shooting an indie movie with your own vision. How did you navigate that?

It was actually a benefit because I did know the show so well from the inside out — I know the actors, I know the crew, I know the vibe on the set, I know our rhythms as a cast. That made it all the easier for me. I knew the visual language of the show. It definitely made me have much more admiration for directors who pop in to different shows and have to be the new guy on set and learn everything.

Would you want to do that?

I don’t know. I’m not close to it. I genuinely love the experience of directing and working with actors. I can easily see it being something I continue to do. There is no reason why I can’t continue acting and directing and producing and find time and room for all of those things. Maybe not all at the same time. But more and more, I’m open to my experience as a creative person and a storyteller, going down paths that may have scared me before.

Superstore is your first straight-up comedy, and it’s going well. The show just got renewed for its third season.

Comedy was never my goal or my wheelhouse. I grew up doing plays and musicals, but if I had a choice between the comedy or the Shakespeare play, I was going out for the Shakespeare play. I never imagined that this is the direction my television career would take. Betty was certainly a comedy-drama. It had elements of both. But it’s been a real challenge, and actually a wonderful education about what’s possible inside of comedy. Sometimes the only goal is to entertain, and there is value in that. But I don’t think comedy exists without commentary. There has to be a truth to it to make us recognize it. And to place a comedy in a big-box store, which is the cross section of so much of America — working America, corporate America, consumer America — it’s a wellspring for touching upon real life.

Amy seems very different than a lot of the characters you’ve played, who have been strong young women. Not that she is weak, but she seems resigned, like she is not really fighting for her life in the way Betty was, or even the character you played on The Good Wife. Amy is struggling more, and I was wondering what it’s been like to play that?

I definitely know what you’re saying in terms of Amy being less of a go-getter and world changer and force, and that is part of what intrigued me about the character. I don’t think, however, that she’s any less comfortable in herself and her choices. There is a real beauty and strength to someone who, like Amy, has decided what’s valuable to her in her life. We tend to think of ambition as something that makes you a good person in our society. But we don’t often think of people who are quietly living their lives and their values and their priorities as strong and valuable and okay. And even in the course of the first season, you go from Amy never expecting anything to change to accidentally leading a walkout, which she would’ve never imagined herself. Even though I don’t think every character has to be out there changing the world or going after great things to be on an interesting track, I do think there is a piece of Amy’s journey, however small it may be, that is about awakening to something she lost a long time ago.

You started your production company, Take Fountain Productions, in 2015. Is there something driving you towards going behind the scenes more? Do you want to have more control of the creative process?

Well, producing I’ve been doing for a number of years, probably since before Ugly Betty actually — my friend’s independent films, that sort of stuff. Most recently, I started a production company and have developed television. That always felt really natural to me, collaborating with writers. And even as an actor, what I love about the process is talking to the directors and the writers and discovering it. It felt natural to parlay that into producing stories I really thought should be told. I feel driven, as a woman of color who has access, to use that to create opportunity for certain stories that other people may not be paying attention to. There isn’t a majority of people out there searching to tell the kinds of stories I’d love to see. The truth is, the stories need to be authentic, and that authenticity comes from a place of experience. As a producer, that’s what I have to offer — my experience that’s unique to my life that another producer may not be able to relate to or protect.

You’re close to making a distribution deal on Gente-fied, a show your company developed. Can you tell me a little bit about that project, and why you were drawn to it?

Gente-fied started out as a digital series with Macro Ventures. I loved the scripts by these two young writers, Marvin Lemus and Linda Yvette Chavez, two California-born Latinxes, which is a term I didn’t even know until I started working on this project. I had to go look it up. It turns out I’m a Latinx, so that’s great. [Laughs.] But I read the scripts, and it was so refreshing to hear the specificity of their voices and the uniqueness of their experiences coming through their writing, through the lens of Boyle Heights. It really is the exploration of this neighborhood yearning to grow, but also wanting to honor itself and stay rooted. It is very much the manifestation of what immigrants, or children of immigrants, go through in this country. Probably people who aren’t immigrants go through that as well. You want to honor your roots and your past, but you also want to burst at the seams and grow into something new. That inner struggle is something I so relate to, being the daughter of immigrants. I really, really struggled with my American identity versus my Latino identity growing up. And I never saw that struggle portrayed around me so I felt very alone in that, only to grow up and realize, Oh wait, we all feel this way? It’s also really wonderful to see the diversity within the Latino community that I’m so well aware of — the generational gaps, the cultural gaps, the class gaps.

There are even East Coast/West Coast differences in terms of Latino immigrant life.

There’s so much that defines that experience, and it’s different for everyone. So it’s amazing to get to delve into a world that is majority Latino, but everyone is so different and unique, when what we’re used to seeing is one character encapsulating all Latinos because there is one in a cast of 50. Something that sets young Latino people apart is we are deeply tied to the generations that come before us, and we have a responsibility and an ownership of their experience and their struggles. They are intertwined. We’re not raised to grow up and grow beyond what you come from and cut ties. We are taught to inherit and take on the experiences of our previous generations.

The fact that Gente-fied is a comedy is also really compelling to me. Because we are used to seeing ourselves through poverty and crime and devastation. We are portrayed as less than, as victims, as drug dealers, as pregnant teenagers, cholos, gangsters, and there is such a heaviness to it. Yet our culture is so vibrant and we have so much life and energy and humor, and we never get to see that part of it. That said, there’s nothing wrong with those images. Those are real people. The only reason we’re sick of drug dealers and housekeepers and gardeners and immigrants crossing the border in every movie with Latinos is because we are so much more than that. Those people exist, and they deserve to be seen in complex and human ways. But that’s not all we are. So what we hope to strive for is more complexity in how we are seen in society. Latino actors and actors of color should have the freedom to portray whatever character speaks to them that they want to portray, and the moral code of that character isn’t a reflection on all of Latino society or every Latino person. But it’s different for everybody, and it’s a journey to figure out.

Last year, there was a conversation around female actors wanting to take more control of their careers — they want to produce and direct more, to create more opportunities for themselves and others. Are you also motivated by that?

This is a hard industry to break into no matter who you are. It’s very, very clear that there is a massive imbalance between women behind the camera and men behind the camera. And if we want the stories and the images that we see out there to reflect more of our experience, we need to find ways to increase the number of women telling those stories. There’s no silver bullet, but for those of us who have the access, if we are not taking the plunge, how can we expect people who don’t even know how to get their foot in the door to take the plunge? That doesn’t mean that every actor should be directing or every producer should be directing. It just means that more and more women are probably asking themselves, Is it something I want to do, is it something that I feel compelled to do, and if so, what’s stopping me? That is definitely how I came to it. I have this wonderful show, this wonderful access, this wonderful opportunity. I go around talking a lot about how we need more female storytellers and women behind the camera, and I am a woman and somebody who loves to tell stories, and it was scary for me. So if it’s scary for me, somebody who has had massive exposure to life on a set and what it means to make a TV show, then imagine how much scarier it is for someone who has no idea where to even begin. Part of the challenge was daring myself to step up and take it on.

You wrote in the New York Times about your first triathlon, and how it took years of therapy to get you to a place where you could do something like that, to get that voice out of your head.

I’m training for another one now. I started therapy, like, it’s almost been a decade. It was for a lot of things, but I think a big, big, big part of who we are in the world has to do with what we believe about ourselves. And for me, I hadn’t even explored what I believed about myself when it came to being a director, a leader, a storyteller, and my capacity to do it. I hadn’t really entertained the idea of doing it, so I didn’t have to ask myself, what’s stopping me? Once I started to see it as something I would like to do, then I had to start asking myself, Well, why am I not doing it and what’s standing in my way? Truth be told, a lot of what was standing in my way was the feeling that I might fail. Fear of failure stops us from doing a lot.

Do you think it was cultural? Did you have ideas from your upbringing that your dreams weren’t supposed to be so big, or was it something else that was holding you back?

It’s hard to pinpoint. I definitely grew up with a mother who told me I could be anything I wanted to be. She didn’t necessarily want me to be an actor [laughs] and understandably was afraid of whether or not there was any opportunity there for me. I was too naïve to really know and understand that the odds were against me. And here is another place where what you believe matters, because I just believed, This is America! If you work hard, eventually you’ll get there. That naïveté served me because I had all the other opportunities and circumstances in place to help me take advantage of that opportunity when it came. In a way, I feel very torn about the values and beliefs that helped me get to where I am. I see the flaws in the notion that that’s true for everyone, because it’s not true for everyone. But I can’t see a world in which I could have achieved what I did without those beliefs, because the truth is, for people like me, when I was 17, there weren’t a multitude of opportunities. So my mom wasn’t crazy to think that may not be a very good direction for me.

I do think that, culturally and societally, failure isn’t encouraged. And when you feel like you represent more people than you, whether it’s because you’re a woman or you’re a person of color or you’re the first in your family, the failure has even higher stakes, and so we edit ourselves because we think, I’ll do what I’m good at. I’ll do what I know I can succeed at. Not so much, I’ll go take a chance and I might fall flat on my face, but that’s okay. And you can’t get anywhere unless you’re willing to fall flat on your face.

How do you feel about your public role representing Latinos?

It’s different for everyone, and it’s been a long journey figuring it out because I started working when I was 17. I came out the gate with Real Women Have Curves, which so many people related to and thought that that character represented them, whether they were Latinos or heavier-set people or anyone who had a bad relationship with their mother. I had gay African-American men coming up to me at film festivals and saying, I’m that little chubby Mexican girl. I have never thought of my work being representative of somebody’s experience as a bad thing. Certainly, as I’ve said before, I’ve struggled with my own relationship to my identity, so it was a little discombobulating to start working as an actor and then be held up as, like, a Latina actress who represents the Latino community when I was still trying to figure out what being Latina meant to me, you know?

I remember when I talked to you many years ago, you spoke about growing up in the Valley and never even going to a quinceañera.

I grew up in the Valley with mostly bar mitzvahs and Jewish friends; I also went home to a mother who spoke Spanish and loved that part of my identity. But it was never clean and clear to me what it meant to be “Latina,” so I think I had to figure it out. And where I am with it is, I feel honored and motivated and driven in everything I do, not just as an actress, as a producer or director, but as a person in the world, as an activist, as a citizen to represent people. For me it’s gone from I don’t know what this means, what am I supposed to do with all this responsibility? to knowing and really loving that if I’m doing something and I’m doing it well, and I’m telling a story that’s never been told; if there’s somebody watching, whether they are Latino, a little girl, whether they’re an older woman, whether they are a gay Asian kid in the middle of the country; if they see themselves represented in my performance, that’s not a burden to me. That’s a gift, and it gives the work meaning. I don’t know if that will change and grow into something else, but that’s how it feels now.

You’ve become a powerful activist for the Latino community, for women, and for the LGBTQ community. Do you see that type of work taking over your artistic career in today’s political climate?

The common way to look at it is, This thing I do takes away from that thing I do. I think that’s a really negative way to look at it. I am not just an actor, I am not just a Latina, I’m not just an activist, I’m not just a director, a producer, a creative person. I’m all of these things, and I’ve finally come to a place in my life where not only is it okay for me to feed all of those things, but everything gets better when I do. I’m not going to stop being a person in the world because I’m afraid people aren’t going to see me as an actor. I’m not going to turn down a Latino role because I don’t want people to not see me as everything else. I am happiest and most fulfilled when I am nourishing and giving time and energy to all the different aspects of who I am. And I can’t control how people see me. I can’t control whether when someone says my name they think of an actress or an activist.

You gave a powerful six-minute speech at the Women’s March on Washington in January. What was that like?

Just being there at the march was magical, as everyone who was a part of it felt. There was a bit of dread I felt leading up to it because of the fear and the sheer disbelief of what was being said and what was happening after the election. But that all went away when I got there and saw hundreds of thousands of people walking through the streets from everywhere, who came to stand together. It immediately became a celebration of our unity, of goodness, of being alive, of standing up for what’s right, about standing together. Just being there was so energizing and overwhelming.

I’ve never addressed a bigger crowd in my life [laughs]. But what I was thinking about were the millions and millions and millions of people who needed to hear that they weren’t alone, that we weren’t going to abandon them, that we are here and we’re in it. Whether you’re an immigrant or whether you’re Muslim or whether you’re black or poor or gay or trans, that you weren’t alone. That doesn’t mean there aren’t going to be very hard times ahead and that there isn’t reason to fear, but there is also reason to be hopeful. What was on my mind when I was giving that speech is, We need this, I need this.

I remember your Instagram from the morning after the election. Your pain was palpable, and it was the same pain many people felt. But shortly thereafter, you kicked off “I Will Harness,” a 30-day online campaign to help communities organize and set goals. How did you go from the despair to that call to action?

I felt like I had been mourning throughout the campaign. I had been watching slack-jawed at everything I believed this country stood for be ripped away, and not feeling like there was an appropriate response to it. When you watch something happening that is wrong and you don’t see an appropriate response to the wrong thing, that is terrifying and heartbreaking and traumatizing. I felt like that had happened over and over and over again throughout the campaign.

So on election night, to feel like all of those abuses were validated, to felt like the end of a certain value system, the end of feeling like I knew what my country was. And, in a way, a sort of coming of age all over again, of waking up out of a certain naïveté that I guess we were all living in. It was like learning all over again for the first time that your parents aren’t perfect and bad things happen in the world, you know? [Laughs.] But times a million. I felt that from almost everyone I came across. So what I needed, and what my husband needed, and what we felt our community needed, was community, was the physical presence of other people to not feel alone. We just started gathering our peers, our friends, together, but also to talk about how we move forward and how we harness this energy that seems by all accounts unprecedented, certainly in my lifetime. It grew from there, and we’re still figuring it out. Everyone’s still figuring it out. Everyone is trying to understand what this is going to require of us. And we don’t have all the answers, but we do think that what really matters is that we build community beyond social media. Because, yes, it has an impact, but on a human level it doesn’t replace the experience of marching with 100,000 people. It doesn’t replace the experience of learning about an issue you thought you knew about, but you actually had no idea until someone who has lived it is sitting across from you and giving you their testimony. We are in a time where people are open to maybe hearing more and listening more. So what we’re trying to do is create spaces where we can have hard conversations and learn what we don’t know.

Do you think you’d ever run for office?

It has never been part of the plan but, like I said, I don’t think any of us knows what lies ahead. And I will say that for a lot of people, myself included, the current situation has really put into perspective what matters. We all have something to give, and it doesn’t seem like there’s ever been a more important time to ask yourself, Who do I want to be in this unprecedented era of this country figuring out what it is? So I don’t know. I think that the answer is I don’t know. I don’t know anything. [Laughs.]

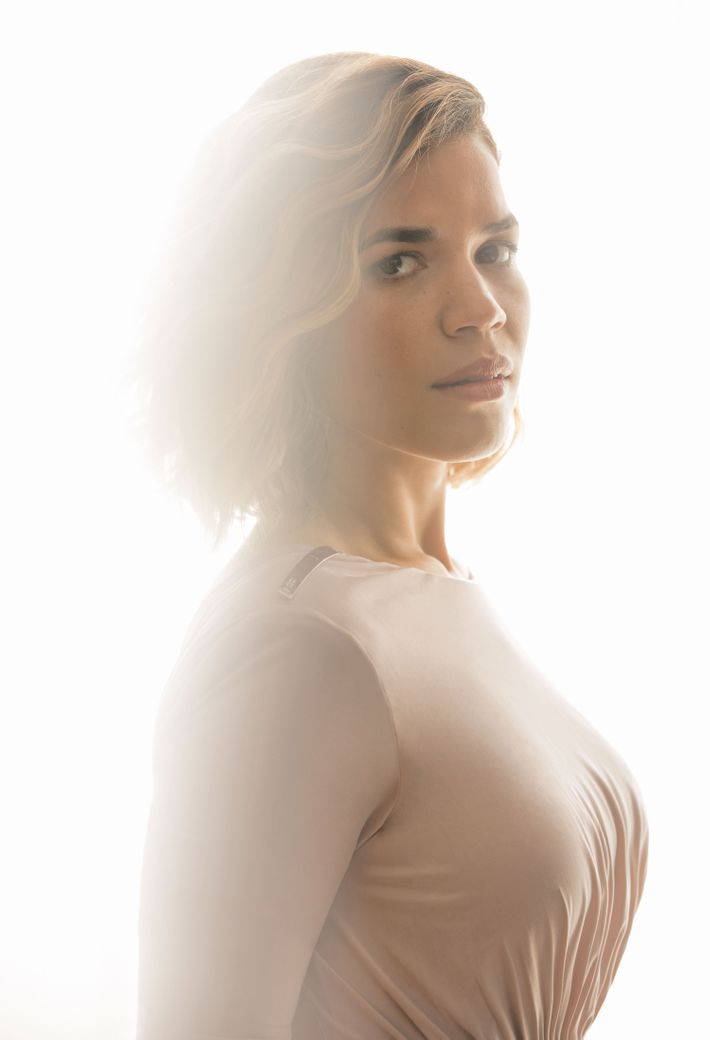

Styled by Tiffani Chanel with The Wall Group. Stylist Assistant Rossana Tornel.