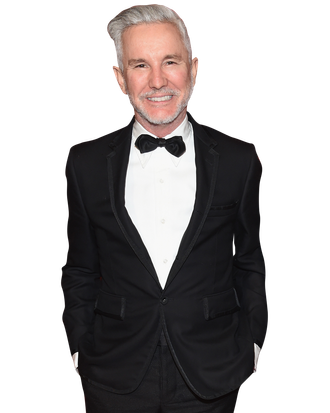

Update: Now that the second half of season one has premiered, we’re reposting our March interview with Luhrmann and including some additional plot-specific questions about some big events in part two. Spoilers ahoy!

Baz Luhrmann’s ambitious musical drama The Get Down landed on Netflix last summer with a twist. Instead of the full season debuting at once, only the first six hours — marketed as “part one” — were made available for streaming. The second half of the season, Netflix promised, would follow early in 2017. That day is almost here: The remaining installments begin streaming April 7, and to hear Luhrmann tell it, all parties involved are intent on making season two happen.

In an exclusive interview with Vulture, his first to promote “part two” of The Get Down, Luhrmann says that he, Sony, and Netflix are working on a path forward for the show, even though the director has said he will be less involved in future seasons. During our discussion, Luhrmann also talked at length about how splitting the season allowed him to shift the show’s direction, what the key dramatic tensions of part two will be, and why he and the show’s writers decided to introduce an eye-popping new storytelling technique.

The Get Down was conceived to be like every Netflix show, where all episodes of a season debuted at once. Then the decision was made to split the season into two batches. Once that call was made, did you also change your approach to how you told the story?

Yes, yes, and yes. Yes to everything. Yes to everything for this reason. One, it wasn’t exactly my decision to split it. We talked about it. There was a nervousness that it would take too long to [finish all the episodes]. The show was, from day one, so ridiculously ambitious. And before we went out, it was always a bit like, “What is it?” But since then, we developed a very strong fan base. Netflix are very guarded about numbers and facts, but I think if you check it out, you’ll see that it’s been reported widely that it is the biggest African-American/Latino show that they’ve got, right? And it’s not just that as the fan base, because we are huge in Berlin and in France and also South America.

Now, I think what’s really attractive for storytellers across the board about this new streaming environment is the ability to be connected with your audience and be able to do two things. One, respond to them, really connect with them. And most importantly, you’ve got the freedom to do wild experimentation that you otherwise would not be able to do in a motion picture. In a film, you really have to lock in your vision a year ahead. You might be able to tweak a bit, but you can’t actually take some big lateral leap a year and a half later. Whereas with this, you get to be incredibly nimble. You get to respond to a very, very present audience. Also, the world changed at the end of last year. As we were making it, we were able to feel that. So yes, the gap really influenced the way we went about things, for sure.

Were there any things, specifically, that you learned from those first episodes that led to you evolving the second half?

There were a couple of things. Because of the weight of [the history involved], we were extremely insistent in working with the Bronx community, in working with everyone from professional storytellers to people from the neighborhood. It was really like a community project at times. I know that sounds crazy to say, but it really was like that. In the first part, I was really conscious of making choices that let everyone know who wasn’t there not what it looked like from the outside in — because from the outside in, the Bronx looked absolutely desperate — but from the inside out. What was it like to feel like you created your own world, you were a superhero, that you could take two records and magically make music? Or write your name on a train and risk your life doing that, because there were no painting classes? We were very, very particular about trying to get the balance between the realism and the kind of heightened nature of the story.

In the second half, it was really clear once the fans got hold of it, that [the heightened part of the story] was what our audience was responding to. Of course it’s fictitious, and of course it’s amplified in a slightly mythical way — but then, that’s how the characters saw their world. That’s how they felt alive and relevant. In the same way that the Wild West has been amplified and mythologized for the bigger truth to be revealed.

So basically, you decided to worry less about telling the larger story of the Bronx and that era.

Yes. The burden, somewhat, of being reverential. We tried not to be [too reverential] in the beginning. But now that we’ve done that, we’ve set up the world. This is actually about people. The real focus here is about the emotions of these young kids and how they evolved into adults.

What was your main focus for the second half, story-wise?

There were two things I think we really focused on. One, there is no question that the emotional relationship between Books and Mylene and Shaolin was central to the story and had to be kept as central as possible. There was no question that those three characters represented three completely different roads. And two, this idea of seeing it from the kids’ point of view in a heightened way. For it to be a memory, be it through a comic book or through Mr. Books, who is on stage [in the future]. We were a bit more daring about going with that perspective. There are many, many documentaries about the subject, and there will be even more brilliant ones coming, I hear. But this isn’t a documentary. This was about amplifying the human spirit that made that time an extraordinary, creative time, a time that could stand up against the negativity that was raining down upon it.

Any other big difference between the two halves of the season?

The first half is a little bit more naïve. It’s a little bit more childish. Whereas the second part, as they grow like adults — I mean, really, a year is like five. As they jump forward [from summer 1977 to fall 1978], the style of the show has a little bit more edge and complexity. It’s about their feelings, their humanity, their relationships, their passions, their desire to be together, their desire to be creative, and their desire, above all, to be someone.

That struggle for success is a big theme, too.

Yes, and I think the universality of that is, you don’t have to be a budding disco star or a young kid who has discovered a new form of poetry over beats, to find that success can get in the way of a relationship. Anyone can relate to a moment when they have to choose between the personal and being with someone that they’re profoundly in love with. That is the central feeling that we wanted. Absolutely, that’s what it’s about.

Based on your Twitter, you actually didn’t finish editing part two until January, even though it was reported you’d wrapped shooting all the episodes before part one dropped last August. Did some additional shooting take place after August?

Yes. We were reshooting up until I couldn’t reshoot anymore, really. It’s not full-on reshoots, because of the nature of the piece. The truth is it’s the same process that I found [in] doing Moulin Rouge — doing something that is highly stylistic, shooting elements. Everything is musicalized, so you had to constantly sort of appliqué it. So we wrapped principal [photography] in summer. We definitely did a little bit more shooting after that. The nature of someone like me is I will always try and make it as best as it can possibly be, you know? I never feel I’ve got there on anything I’ve made.

A recurring visual element in the new episodes is animation, which pops up unexpectedly over multiple episodes. Did you add this to your stylistic arsenal to push the story in ways you couldn’t with live action? Was it because you’d already wrapped principal photography, so animation was the only way to make the changes you wanted? Or was it all of the above?

We were always going to have a little bit. As we started doing it, we discovered that you could push some of the more poetic, fantasy elements in the animation that you simply couldn’t do in the realist footage. For example, there’s only so much that dialogue is going to be able to tell you about Dizzee and Thor, because they’re not very verbal. Whereas in the animation, going inside their own fantasy and understanding how they are living in their own artistic fantasy, it allows you go to with them.

When the first half of the season came out, I know you had to deal with reports about the show’s cost. Was it difficult to convince Netflix and Sony to approve spending more money on a new element? Or was it more cost effective, since animation of this type tends to be less costly than traditional filming?

Let me just say about this: Was this show the most expensive show ever made? No. Was it cheap? Absolutely not. It wasn’t cheap because it was ambitious. And you know what? I think that this subject deserves a high-end execution, and Netflix were absolutely unflinching in that. They really were. The money, by the way, for the animation? You’re actually right. The animation was a better way of doing it financially than if you tried to do those complicated things with CG or whatever. So financially, it was good. Nothing is ever cheap. Please, a shout-out to the animation guys: They were awesome, just incredible and so passionate. And the truth is they did it for a really good number. Other things were not financially easy, but that was not a burden.

The second half will be five episodes instead of the expected six, which means season one will be a total of 11 episodes, rather than the 13 Netflix initially ordered or the 12 most of us have assumed it would be since last August. What happened?

When we first started working on the show, an arbitrary number of 13 episodes was identified. Once we delivered the first six, as we discussed before, we were influenced by how the fans were responding, what they were connecting with, and also a discovery from working in the form. For us, it was really like a long-play movie. We were particularly concerned with making sure, with the musical numbers and density of each episode, that we weren’t finding ourselves “padding” in material for the sake of a making a number. Ultimately, Netflix and Sony agreed we should make the number of episodes that we all felt best suited the length of the show and gave us the best ending. Therefore, in part two, we decided on five episodes with the finale being longer [about 75 minutes].

Let’s talk about the possibility of season two. Did you make the season one finale expecting to get another batch of episodes, or thinking this would be it? And if there is ultimately a season two, how involved will you be?

To be honest, we have already developed the opening of the next season. Sony and Netflix have been very driven about having a second season. There has been no question about that. They really want it. The issue is, and it is a simple truth: I never saw myself as the showrunner. I didn’t even know what that was. We tried to find the appropriate people to [serve as showrunner], guys who do that, and they were great. And they had great credentials. But it just wasn’t moving forward. At some point, Sony asked would I come and get more involved at the center of it. And I did. I just did everything I could to keep it creatively moving forward and keep the standards up.

But you don’t want to serve that role in a season two.

I cannot really be at the center of it. At a certain point, you go, you know, I have a family and I can’t be central to it, and I don’t think I should be. Having said that, way back in the very beginning of this, and I won’t say who it was, but there is an African-American director who is absolutely the best of the best for this, and always was. I tried to get him involved and I couldn’t. I don’t want to be tease-y, but we’re all trying to hope to make that work out. That’s what we’re hoping. As Cindy Holland of Netflix said to me, “We are not in the habit of creating awesome characters and then throwing them away.” I thought that was a great quote. She said these characters live, and it’s our responsibility to try and find a way that they live on. That’s what we want to do. Is there formally a second season? No. I know they want it, and we’re trying to find a way that that can happen.

So you just need to find the right person to come on as showrunner.

Yeah. We know the person we want it to be. There are others. But that is exactly right. And then I can go back to being what I always was going to be, which was kinda Uncle Baz. I would see cuts, and have a point of view, but be like an executive producer — a guy that was a well-wisher and a supporter and a giver of notes.

Now that season one is done, what was the overall experience like to make a TV show for Netflix and Sony?

Were there bumpy moments and a bit of a line drawn sometimes? Not really. I’ll tell you what it was. Both entities were totally in love with and completely passionate about the subject matter. They were just overwhelmed by it. And Netflix, they go the extra mile if they really believe that they have believers making the show. Everybody involved in the process was passionate. There was no nine-to-five about this at all.

Do you think you’ll do another TV show?

I do. I am exploring movies right now. But now that I’ve experienced Netflix, what I think is, I could almost go to them with anything. It might be documentary and it might be drama and it might be — I think if I had a very experimental, creative thing, they would be my first port of call. In fact, I’ve got one in the back of my mind. At some point I’ve gotta just slow down, ya know? I’m not a spring chicken.

So let me ask you a few questions for after people have seen the end of season one. We’ve sort of assumed Books becomes a huge star, since he’s been narrating the story from the future. In the finale, you seem to hint that Mylene also is still a massive star in the future? That’s her we see going on stage in the final moments, right?

I gotta tread really carefully. We haven’t completely answered it, but I will tell you one thing. In the journey of Mylene, disco absolutely crashes. Assume it. Mylene, coming from being in a place of being in the most powerful music form, will be now in the least powerful music form. Now, there are several stars you can look at who were riding the crest of the disco wave [and survived]. What happens is, popular music takes a big turn. R&B takes a big turn in the ‘80s. And it’s revitalized, and it comes back in a completely different way. Michael Jackson has a lot to do with that. So I’m not gonna say what the plot is, but she has a chance — after a difficult time — of a resurrection. You can assume that she has a musical life.

This season also showed she can do more than disco. For example, with “Toy Box,” the big production number and song she does at your Studio 54 stand-in. This is a bit of a criticism, I guess, but as entertaining as that scene was, the song felt to me immediately anachronistic. It felt much more like a Britney Spears song from the early 2000s than a disco song. You have a reputation for putting together musical numbers that sort of transcend the rules of space and time, but what was going on in this case?

This is how it works. Sia is a very good friend of mine, and she wrote several songs, and that one was really right for it. What happened with it was we tried to do a disco version of it, and it really never played. Whether you accept it or not, it just has a better effect of being more — it’s kind of ‘80s pop. Trying to make it more ‘80s pop just works better for the song; that’s the truth of it. So we were sort of taking license and saying, “Well imagine in the [future], that’s where she’s kinda heading.” We tried to do a version more like “Love to Love You Baby,” that kind of orchestral arrangement, and it just didn’t work with the structure of the song. So the solution was to go more ‘80s pop.

And when Sia gives you a song, you use the song. Sia wrote “Toy Box,” and she also wrote, which I really love, “Telepathy,” the one when the boys kiss in the vogue-ing club. She is a songwriting goddess.

Another unresolved question of the season: What are we to assume about Dizzee and that train?

That one I have gotta leave you to interpret.

That’s a cliffhanger?

Yeah, it’s a cliffhanger.

One person we definitely know is dead is Ramon. Was this always the plan when you hired Giancarlo Esposito? Was this the only way that Mylene could be free — he needed to be gone?

I knew that [Giancarlo] was gonna be limited. Early on, we knew that. Look, if you go back, you can see Giancarlo is already setting up very early on that he is a little bit on the edge, psychotically. In a sense, her father was the star of the family and his kind of ballooning ego — that was something we were always gonna toy with. So we knew there’d have to be a death, but we just didn’t realize how strong we’d go with it. I don’t know how it played for you, but we really committed to the idea. So yes, we knew we’d probably do something tragic with Giancarlo. And Giancarlo was like, “Can you give me a great exit”? I think he got one.

This interview has been edited and condensed.