Before I became a critic, I was an artist, and for about ten years, beginning in the early 1970s, I feverishly devoted myself to a single, gigantic project: illustrating the entirety of Dante’s Divine Comedy — starting with Inferno.

By 1978, I’d had two solo shows, both of which sold out; museums bought my work; I was reviewed favorably in Artforum and also had my work shown in the proto–Barbara Gladstone gallery in New York and by the great Rhona Hoffman in Chicago. But once I quit, I quit. I never made art again and never even looked at the work I had made. Until last month, when my editors suggested that I write about my life as a young artist. I was terrified. Also, honestly, elated. No matter how long it had been, I admit I felt a deep-seated thrill hearing someone wanted to look at my work.

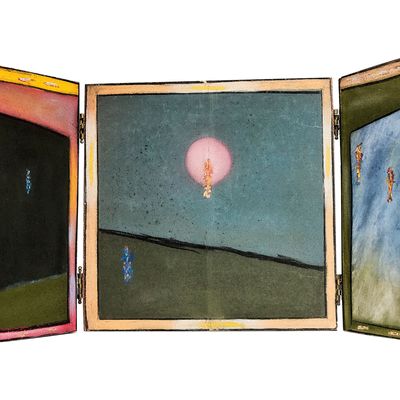

The slideshow that follows is a selection of the work I found when I finally looked inside portfolios I hadn’t opened in 35 years. Each image is a drawing that doubles as a kind of study for an altarpiece — I imagined I would make 100 altarpieces for each of the 100 cantos of the Divine Comedy. Each altarpiece was a wall-based sculpture that could be viewed open, showing three panels, and closed, showing two panels that would often compose a single image (the images above are of one finished work I was able to track down, though it isn’t my favorite!). The project was meant to take me 25 years, but I only made it to the fourth canto by the time I quit; nevertheless, in that time I had developed an unbelievably intricate language that would allow me, a technically poor draughtsman and even worse painter, to depict Dante’s complex narrative. Here, with altarpiece drawings for each of the first four cantos and a few maps I made of Hell along the way, I’ll try to explain just what I was thinking.