In May 1985, Esquire magazine published an essay by a twenty-three-year-old Yale graduate named David Leavitt, who set out to do nothing less than explain his generation. It belonged to a long, dubious journalistic tradition in which a major media outlet sums up young people for its readers, using an envoy from their tribe. These stories follow a certain script: Mix some reported anecdotes with a few references to politics and pop culture trends, add a tone of alarm, and then draw a sweeping conclusion about wildly different groups of young people. The piece’s title: “The New Lost Generation.”

Leavitt argued that those coming of age in the Reagan era saw the idealism of the 1960s vanish and substituted a cynical and steely veneer. They sighed at political activism and rolled their eyes at passion and engagement. Unlike the hopeful kids from past decades, they were not marked by a particular cause to fight for. They were more likely to find all of politics contemptuous. What united them was a jaded outlook about not just politics but even the nature of honesty itself. “We are determined to make sure everyone knows that what we say might not be what we mean,” Leavitt wrote, building to a crescendo: “The voice of my generation is the voice of David Letterman.” By the next year, David Letterman not only had won Emmy Awards for the third year in a row but he was also the co-host of the awards show, with Shelley Long. He appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, Newsweek, and Esquire. Doing a guest spot on his show became as much a status symbol for performers as making Johnny Carson laugh. “You wanted to impress him,” Martin Short said of the reputation of the show among guests. “You did certain shows where you couldn’t give a shit if you impressed the host. But this was the hip show. Tom Hanks would say the same thing. Steve Martin would phone me up three months before appearing on Late Night with a potential bit and say, ‘Tell me if this is funny.’”

Late Night had not become as popular as The Tonight Show, an impossibility, considering their respective time slots, but its cultural impact had surpassed it. By the middle of the decade, Letterman was the rare host who stood for something bigger than a television show. He was increasingly mentioned as the talk-show avatar of post-modernism, a movement marked by self-awareness and challenges to dominant narratives that was then shifting from academia to the mainstream press. He became the host who didn’t believe in hosting, a truth-teller whose sarcasm rendered everything he said suspect, a mocking challenge to anyone who pretended to take the ridiculous world seriously. Letterman became the face of an ironic sensibility that permeated comedy, television, and popular culture.

Letterman’s early years satirized the show business world, but as his aesthetic strains hardened into conventions, he began to create his own, with distinctive rituals, codes, and in-jokes. Late Night’s humor transformed from being mostly reactive to establishing its own eccentric voice. The evolution of Paul Shaffer was part of this shift. He began the show playing a caricature of a Las Vegas entertainer, a spoof who parroted cheesy lines designed to be smirked at. But after a year, he started to fill out his character, improvise more, and become his own kind of oddball sidekick. “Dave got through to me: Let’s just have a conversation,” Shaffer said. “I also ran out of clichés.”

Shaffer, who increasingly acted in sketches, doing the kind of physical comedy and character work that Letterman shied away from, built up his role as part of an absurdist double act with the host. In one episode, Letterman and Shaffer had an extended argument about whether or not the show they were appearing in was a rerun.

On the eve of his fourth-anniversary special, Letterman mused about what would happen next. “Then the exposé comes out,” Shaffer said. “‘The David Letterman Show: What Really Happened Backstage.’” Letterman laughed, then tensed up. Even though this was an obvious fiction, the prospect made him visibly nervous. A deft reader of his host’s moods, Shaffer added: “I’m not going to talk to the people.”

Letterman responded, “I appreciate that. Don’t talk to them,” and then grimaced, balled up a piece of paper, and tossed it behind him at a fake window, triggering what had become a familiar sound effect: a canned window crash.

In exchanges with Letterman, Shaffer often played the ham or the beleaguered fool. On one show, Letterman’s insults on the air stung a little too hard even for Shaffer, and he called Dave the next day to say he’d gone too far. “David said, ‘You can come back at me,’” Shaffer recalled. “We’re just trying to fill the hour by creating some dialogue.’ That changed things for me a lot.”

Shaffer’s relationship to show business became more complex, moving from being a parody of Las Vegas insincerity to something that blurred the line between satire and his real voice, which displayed genuine affection for show business. Randy Cohen, a Late Night writer who saw the show as directly in opposition to traditional show business, thought Shaffer diluted the point of view of the show. “I had a hard time with Paul and his relationship to Vegas entertainment,” he said. “If you laughed because you enjoyed the thing at face value, he’ll accept that. But if you laughed because you thought he was offering this sort of sly dig, he’ll accept that, too. I think he was obfuscating his own position.”

Implicit in Cohen’s argument is that Late Night was a rejection of the values of commercial entertainment, which is how many of the show’s fans saw it as well. But a hit network talk show could exist in opposition to show business for only so long before it also became a part of it. Letterman spent years making fun of the conventions of the talk show, but now he was the host of a popular talk show, and his job was to talk to celebrities. He was a distinct part of the world he was famous for disdaining. Even when he was dismissive of stars to their face, they joined in the joke. You could say that Letterman was co-opted by his own success, but that would imply that he began with more of an intent to disrupt the establishment than he did. It was Merrill Markoe who cared more about challenging the conventions of show business.

What David Letterman was truly committed to was a lack of commitment. His defining feature was not scorn for actors or revulsion toward the theater of the media, but how he surrounded himself with layers of ironic distance, creating an elusive and detached style that had become the quintessential Letterman pose.

Other comics deployed smirking detachment in movies and television. But they weren’t in people’s living rooms every night, talking directly into the camera to millions of viewers, establishing an intimate relationship that is unique in entertainment. David Letterman didn’t invent comedic irony, but more than any other performer of his era, he brought it into the mass culture.

As his reputation became more pronounced, he embraced comedy that turned in on itself and made more shows about the process of making a talk show. He regularly left his desk to go backstage to his dressing room or his office, and often to the neighboring studio. His opening remarks operated on two levels: the jokes and his running commentary on his jokes. The latter often became far funnier and baroque, commenting upon his comments about a joke that commented on something else.

Letterman criticized himself way before anyone else did. As a self-loathing perfectionist, it was a task he was suited for. Even with an ordinary joke, he would constantly signal that he found it lacking, pausing extravagantly, repeating the punch line, then sighing, casting side-eye. “If a joke wouldn’t work,” Letterman said, explaining his strategy, “I wanted to be able to excuse myself from it.”

Many comics, of course, ridiculed their own jokes. But no one fought his own material as consistently and with as much creativity as Letterman. He didn’t just sigh. Letterman looked hurt, off-kilter, at odds with his own material. Sometimes he would stop mid-joke to let the audience know the punch line was coming, or veer off into tangents that made a mockery of his own performance. If one diagrammed the structure of Letterman’s jokes, they would look like a series of concentric circles increasingly putting distance between him and what he was saying. Years before the term “Generation X” moved into circulation, David Letterman made ironic detachment seem like the most sensible way to approach the world.

More than any other comedy figure, Letterman redefined counter-cultural cool as knowing, square, and disengaged. Authenticity, the currency of cool for ages, was out; only a fool still believed it existed. What mattered was signaling that you knew it. You saw this clash of old and new styles play out when the pop star Billy Idol appeared as a guest on Late Night.

Idol adopted a glossy version of Sex Pistols style with all the usual signifiers of a punk rock aesthetic: black leather jacket, shock of white spiky hair, a scowl. Idol told Letterman that his songs were so popular that drug dealers were naming their products after them. Instead of chuckling merrily or changing the subject, Letterman injected some antagonism into the exchange and sneered, “You must be a very proud young man.”

A different host might have made this sound toothless, a self-deprecating remark that drew attention to how uncool he was. Letterman, wearing a suit, tie, and a short, neat haircut, looked like the anxious conservative figure in this exchange. His clothes did not telegraph counterculture rebellion the way Idol’s did. Yet his stern old man’s locution came off as more shocking than anything the musician was peddling. His sarcasm was laced with an attack, striking skeptical notes that refused to take Idol’s provocation seriously. His attitude was clear: Idol was just more show biz. Letterman flipped the script of the rebellious rock ’n’ roller shocking the conformist. He made Idol look like a poseur, a guy trying too hard. They were both fakes, but at least he was willing to admit it.

David Leavitt’s Esquire essay didn’t just trumpet the influence of David Letterman. It also hinted at an intellectual critique of him that would become more common toward the end of the decade. Letterman, the argument goes, was a reflection of the political moment, a figure who, if not in tune with the Reagan revolution, had a disengaged style that provided no opposition. In the 1960s and ’70s, young people embraced antiwar folk singers and polemical comedians who took aim at the status quo. If Letterman was a hero for young people in the 1980s, what did he stand for? It was hard to tell, perhaps nothing. Characteristically, Letterman drew attention to this criticism while making fun of it, wryly saying on three different episodes from the middle of the decade that Late Night was “all form and no substance.” Letterman made engagement itself seem a little ridiculous, particularly any earnest kind. In his history of transgressive humor, Going Too Far, Tony Hendra argued that Letterman made it “bohemian to be anti-bohemian.”

Watch David Letterman’s Most Contentious Interviews

Every night, Letterman invited the audience to join him in mocking something foreign, strange, or other. Jokes can be a cudgel against the powerful, but just as often they create a norm that excludes or stigmatizes difference. As he became more successful, Letterman risked moving from throwing the spitballs from the back of the room to being the one hurling them from the front.

Letterman was no conservative, but he did have a certain aversion to lefty self-seriousness. (“He used to make fun of my Berkeley roots by saying, ‘You were probably off burning goats or whatever you hip people all did,’” Merrill Markoe said.) And in the 1980s, he frequently employed flag-waving images in sketches that riffed on Cold War populism.

Just as he did with show business, Letterman poked fun at gung-ho patriotic fervor in a way that could be seen as indulging in it as well. In one Viewer Mail sketch, Paul Shaffer responded to a letter from the Department of the Army with a rant against warmongers, saying we should cut funding for the military and use the money to plant flowers and support modern dance. In the middle of this parody of liberal do-gooder protest, Russian soldiers entered and grabbed the band- leader, who converted suddenly, pleading, “Nooo. Army, help me!”

Letterman ended the sketch by explaining that it had been a dramatization to illustrate the need for a strong military, then the screen faded to a clip of a waving flag as the host said, “God Bless America.” The sketch was not right-wing. It made fun of a certain simplistic patriotic view, but it also made an ironic joke rooted in a conservative view of the weakness of liberals. In later decades, Letterman would become overtly liberal on the air. But in the 1980s, his politics, like his comedy, was elusive.

Context informs the meaning of comedy, and Late Night had developed into a popular show among young men in the heart of the Reagan era. (In 1986, 68 percent of its audience was in the eighteen-to-forty-nine age group.) Steve O’Donnell said the point of the flag-waving bits might not always have aligned with how they were received. “The joke was on television and entertainment and how cynically they will trundle out something to get a rise from a crowd,” he said. “Sometimes the crowd will respond sincerely.”

The author David Foster Wallace saw something insidious in the triumph of the ironic comedy of David Letterman. He disliked Letterman the way only someone who also loved him could. He wrote about him with the passion of a convert. Early in his storied literary career, Wallace became known for a certain self-referential, hyper-clever literary style, before becoming a sharp critic of these same tendencies in art and literature. He bemoaned the rise of the dominant ironic voice as good for cheap ridicule, but not much else. He worried that it closed off emotional responses, earnest declarations, and other actual expression — irony was good for debunking and exposing illusions, but it was a dead end. To Wallace, Letterman was “the ironic ’80s’ true Angel of Death.”

Few artists dare to try to talk about ways of working toward redeeming what’s wrong, because they’ll look sentimental and naive to all the weary ironists. Irony’s gone from liberating to enslaving. There’s some great essay somewhere that has a line about irony being the song of the prisoner who’s come to love his cage.

Wallace dramatized this condition in a short story, his first published in a major magazine. “Late Night,” which ran in Playboy in 1988 (and was later retitled “My Appearance”), captured what an unusual figure David Letterman had become in the middle of the 1980s.

The plot focuses on an actress preparing to appear as a guest on Late Night with David Letterman. That this show business slice of life plays like paranoid horror is a testament in part to the reputation that Letterman established for treating his guests harshly, which became a concern for him. During commercial breaks, he would ask staffers if he had been too rough on a guest. “The great thing about Dave is, if he wasn’t interested [in his guest], he could turn it into entertainment,” Steve Martin said. “He survived the sitcom actresses.”

He did that by being cutting or dramatizing his own irritation with the interview. He seemed to particularly relish poking fun at female guests. At various times in the history of his show, he made a female celebrity into a running joke that he would bring up repeatedly. He did this to Joan Collins, Oprah, Cher, Shirley MacLaine, Madonna, and others. Cher famously told him on the air that she hadn’t come on his show for years because she thought he was an “asshole.” She was not the only one. The first actress to receive his persistent needling was Pia Zadora, a show-biz lifer. In the first year of Late Night, her name became a kind of shorthand for “callow star.” Letterman clearly enjoyed the sound of her name and would say it playfully, over and over, night after night. He delighted in oddball sounds. When she eventually came on the show, Letterman seemed at first uncomfortable, then rather blunt, then nasty. “There are women your age still waiting in that long, lonely line of show business who feel, you know, envious of you,” he said. She responded, “You’re picking on me because I have a wealthy husband. Look, I can work as hard as the next guy.”

It was an unusually contentious exchange, a departure from the playful softballs that talk-show interviewers typically offered up to actors. It also got laughs. But it was positively collegial compared with the most painfully tense interview of his early years. When the actress Julie Hagerty came on the show to promote a sequel, Airplane II, the result was a cringe-inducing exchange between two socially awkward celebrities. Hagerty was nervous to the point of paralysis, answering questions abruptly, though not rudely. She was polite, but clearly shy. Letterman did nothing to put her at ease. In fact, her inability to perform seemed to anger him, his temper rising.

After a few questions, he didn’t become flustered so much as antagonistic. But the way he communicated his fury was by pointedly matching her in small talk, being boring to comment on her boringness, mocking her through imitation. It was brutal. First he asked mundane questions: Was it fun to work with Woody Allen on A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy? Had she gone back home for the holidays? When she responded with short, colorless answers, he started talking about himself, in a passive-aggressive attack. “I went to L.A. over the holidays,” he said, “and the weather was nice.” It was a classic indirect Letterman insult. “I remember watching that on the monitor in agony,” said Jon Maas, an NBC executive.

Even though he had no connection to Hollywood when he wrote it, David Foster Wallace, in his story, captured the chilling impact that Letterman’s interviews could have on movie stars like Zadora and Hagerty. The main character was nervous, even terrified, about appearing on Late Night. Explaining his story’s provenance, Wallace said that he was inspired by the interview with Billy Idol, but he clearly also borrowed from an appearance by Susan Saint James, the star of the sitcom Kate & Allie, who was married to the NBC executive Dick Ebersol.

The guest in the original story was named after her, but his editors made Wallace change it to avoid any possible litigation. Saint James was actually a savvy guest who never seemed to get too flustered by Letterman’s slights, in part because she was so familiar with his style. (She had been a guest on the first Tonight Show that Letterman guest-hosted). They had playful, bickering chemistry on her many appearances on Late Night. He would invariably open interviews with her by asking if she played Kate or Allie. She pushed back, needling him for not attending one of her parties, and even once brought a clip from her show of a character blissfully ignorant about Letterman. In one interview, she talked about doing an Oreo commercial for fun, and this is re-created in the Wallace story.

But whereas a show business veteran like Susan Saint James was slyly clued in to Letterman’s sensibility and played along, Wallace’s version of her character, named Edilyn, was at first naive about show business, which suited Wallace’s purpose of portraying Letterman as a bullying dark force. The story hinged on the question of how a guest should act to perform well on Late Night. Her husband cautioned that the most important thing was to avoid being sincere. “That’s the cardinal sin on Late Night,” he said. “That’s the Adidas heel of every guest that he mangles.”

After some hand-wringing, she took his advice and performed oily, ironic glibness, presenting herself as a hack and a sellout for his amusement. After being coached by her husband to mock herself before the host does, she announced on the air that she had no talent. By telling the story from the perspective of an actress appearing on his show, Wallace presented a more ominous version of this pop culture transaction than viewers saw. Late Night was portrayed as a gauntlet of ridicule and humiliation you could overcome only by sacrificing a vital part of yourself.

In joking self-deprecatingly, Edilyn won laughs from the audience and from Letterman himself, but at a price. By the end of the story, her performance had created a rift in the relationship with her husband. There was a sadness between them, a connection broken between this couple who now saw each other without illusions. Letterman had shaken their ability to trust their own perceptions of each other. It was a cautionary tale about the danger of ironic distance.

Wallace was not the only literary figure to worry about the cultural impact of David Letterman. Toward the end of the decade, Spy magazine ran a cover story called “The Irony Epidemic,” a manifesto by Kurt Andersen and Paul Rudnick. Andersen was one of the first prominent journalists to recognize Letterman’s talent, but his cover story took a more anxious tone, warning of a pervasive cultural style described as “Camp Lite.” As in Leavitt’s essay about the new lost generation, Letterman was cited as the poster child.

“Camp Lite uses irony as an aesthetic, an escape route. It is a breed of timidity,” they wrote. “Camp Lite can redeem itself, by cultivating some danger, some bracing recklessness, some of the alienating weirdness that spawned it. Otherwise, Camp Lite will remain a smug reflex, a painless roost for guys ’n’ gals without imagination or real spunk.”

That these brainy critiques of Letterman’s style exist at all is evidence of his ascendant stardom and unusual influence. He was being held to the standards of a public intellectual or an artist leading the culture, not just another talk-show host who helped actors publicize a movie. Wallace, Rudnick, and Andersen also located a real pitfall in the style of David Letterman: if he could redeem terrible acting, hack jokes, and stupid pet tricks with the help of a raised eyebrow and a knowing gibe, how could you tell when his standards fell? But perhaps more seriously, they warned that ironic distance limited an artist’s scope of expression.

Alex Ross wrote a perceptive analysis in the New Republic about Letterman that suggested a counterargument. Called “The Politics of Irony,” it made the unlikely comparison between the performance style of David Letterman and that of Rush Limbaugh. Even though they differed politically, Letterman regularly listened to Limbaugh in the mid-1980s and found him compelling. As a former radio host, Letterman was impressed at how the right-wing pundit filled hours of time with meaty monologues of talk. “I thought he was very entertaining and also full of shit,” Letterman said.

Limbaugh had also clearly watched Letterman, and borrowed many of his tics when he had his own television show for a few years in the 1990s, including tossing cards behind his head. Ross regarded both as supremely gifted verbal performers, arguing that Letterman created his own mode of speech out of clichés, strings of banal phrases that, through repetition and attitude, he breathed life into. A guarded Midwesterner whose natural inclination was to hold in his emotions, Letterman was by nature shy, repressed, and not inclined to hit anyone over the head with a message.

For an artist of this personality, an ironic pose helps him find a way to express himself, even if not everyone could detect what he was saying. Letterman often proved himself most articulate in what he refused to say or what he seemed to imply. It was clear when he thought a guest was peddling nonsense or when his jokes were failing.

Ross didn’t see Letterman’s ironic attitude as a dead end for expression, as Wallace did. In fact, it enabled Letterman to use a coded language to say things that he couldn’t say directly. He had become “a sly virtuoso of layered meanings, a contrapuntist of revealed and concealed messages,” Ross wrote.

Letterman smuggled in messages of disapproval or irritation through tone of voice, a glance. But as he built an audience tuned to his frequency, alert to his tells, he was developing more ambitions as a communicator. Ross described an essential attribute of the Letterman style. What he shared with Rush Limbaugh was an ironic mode that reveals itself in reaction to something else. In the case of Limbaugh, the foil was liberal elites, but with Letterman, Ross argued, it was television. These performers were animated by their resistance to and scorn for a dominant language, by rejection rather than creation. This captures something essential about the limitations of David Letterman, which is supported by those who worked most closely with him.

“He’s not a comic, exactly,” Steve O’Donnell said, trying to describe the essence of the host. “But he’s not a broadcaster, purely, either. He’s a personality and a commentator, a responder to things.” When asked about his strengths and weaknesses, Rob Burnett, who would become his head writer in the early 1990s, said his strength was in reaction.

A performer like that needs the right target. In the first years of the show, Letterman found several, none better than television and show business itself. His greatest antagonist was his own network. He had mocked its programming choices as far back as the morning show, but a major event would help him turn this foil into something richer. It was several days before Christmas 1985 when Letterman found a new focus for his sarcasm and, despite being a star, turned himself, onscreen at least, into an underdog doing battle with the powerful.

Letterman began his show reporting some news. General Electric, he announced, had bought NBC. “They’re calling it a merger,” he said, before leaning toward the camera, almost as if he was about to tell the audience a secret. He made an “okay” signal with one hand, indicating that this was clearly a lie. Just in case you didn’t get the point, he added, “It was one of those gun-to-the-head mergers.”

Letterman then imagined the conversation between the network execs and their new owner. “‘How much do you want?’ ‘Six billion dollars,’” he said, setting up his punch line. “‘Okay,’” he responded, voicing the part of the GE negotiator. “‘How much without Punky Brewster?’”

He used GE as a punching bag for the entire monologue. In between scripted jokes, he enumerated the things it had invented, like push buttons, before sarcastically praising how revolutionary they all were. “You know, in the old days, we used a switch,” he said, pantomiming turning a switch on and off, his eyes wide in mock amazement. When Letterman moved to his desk, he didn’t let up, asking Paul Shaffer what he thought of the deal. Shaffer expressed enthusiasm that may or may not have been genuine. Letterman would not have it.

“No, you don’t,” he told Paul. “We don’t want to be taken over by GE. What are we going to do when these knuckleheads come in here?” he said, glaring at his bandleader. Letterman looked strangely angry. “Well,” Paul muttered. “They’re …” Letterman cut him off again: “Listen, they’re wimps.”

Letterman had long mocked or caused trouble for his employers. He did it when he was doing college radio; he did it on his morning show; he did it right from the start on Late Night. Earlier in the year, he had tormented Bryant Gumbel and Jane Pauley from the seventh-floor window, shouting at them from a bullhorn while they were shooting the Today show. But there was something else going on here. When General Electric took over, Letterman found something he badly needed: a good villain.

His anger at General Electric was not an act. It was real. Much more than a stand-up comic, Letterman identified as a broadcaster, and he resented businesspeople who thought they understood better than those in front of microphones. Decades later, explaining his feelings after learning about his new bosses, he sounded just as heated:

I had a degree in broadcasting when RCA was the Radio Corporation of America. General Electric made oscillating fans or something. I didn’t know what the fuck they did. This was genuine. I was up in arms.

GE was a target that resonated, and not just for the reasons that Letterman intended. For the host, GE was primarily an electronics company, but it actually did have a long history in media, which he knew about as well. When Letterman was ten years old, the third highest-rated show on television (behind I Love Lucy and The Ed Sullivan Show) was General Electric Theater. Produced by the public relations arm of the company, the show featured many of the biggest stars of the day putting on crime stories, dramas, and other genres between promotions for GE products.

Its host was the faded movie star Ronald Reagan, who joined General Electric in the 1950s. Working for the behemoth company, one of the original twelve listed on the Dow Jones Industrial Average, Reagan spent two years touring the country, giving speeches at its facilities, and this was when he developed his stump speech about the perils of government overreach and the value of free markets, which sparked his political career.

On General Electric Theater, Reagan played the part of the forward-thinking patriarch showing the home audience the marvelous General Electric products in his own home. He used his real family in the show. And he would preach the gospel of GE technology, telling his viewers that “when you live better electrically, you lead a richer, fuller, more satisfying life.”

This show represented two of the main sources of mockery on Late Night with David Letterman: the hollow promise of new technology and the benevolent television authority figures of 1950s sitcoms. Letterman had already ridiculed such television families with “They Took Our Show Away” and the Christmas special, and his Custom-Made Show was the start of what would become a sustained attack at hucksters of technological progress. When Letterman talked about the new cameras or Japanese technology, he could have been satirizing General Electric Theater.

When Ronald Reagan was running for president, clips of General Electric Theater were often shown on television and used as jokes about the absurdity of having an actor as commander in chief. It became a comedy cliché of the 1980s. “The writers and clip guys were always mentioning the old GE Theater as some kind of potential wraparound,” Steve O’Donnell said, referring to a premise for a comedy bit on the show. He added that it seemed too politically on the nose and hack for Late Night. Still, Letterman jumped at the chance to skewer General Electric.

David Letterman was not a comic who believed in only punching up. He mocked eccentrics and outsiders, whether it was immigrants or people from small towns (this was part of the premise of Small Town News) or the overweight (he had a weakness for fat jokes). His tense interviews could come off as mean, and once he became a star, his aggressive brand of comedy risked looking petty.

Building General Electric up as the enemy enabled Letterman, at the height of his cultural influence, to reclaim the role of the little guy. It also put him in the tradition of comedians saying the things to their bosses that you always wished you could say to yours. Letterman, who still wanted to be seen as an underdog, turned Late Night into a drama for playful complaints about the corporate giant. He staked out his most aggressive stance toward his bosses in April 1986, when he ventured out to the headquarters of General Electric to give them a welcoming gift, with a camera crew in tow. With his arm around a large fruit basket, he entered the revolving door, only to be stopped by security. “We received your letter,” a woman told him, adding that he had not gotten authorization. “We need authorization to drop off a fruit basket?” Letterman asked.

Randy Cohen had the idea to do a remote piece on getting to know GE. And they spent the day visiting GE appliance dealers, washing machine repair shops, and other stores. None of that footage was used. The short video became Letterman going to the headquarters to deliver a fruit basket.

It was the kind of gonzo stunt that Michael Moore would turn into a trademark only a few years later in the documentary Roger & Me, which he started making around the same time that Letterman showed up unannounced at General Electric. Moore also played the ordinary working-class guy walking into corporate headquarters — this time at General Motors — looking for answers or at least some semblance of humanity, after massive layoffs. His clever editing also echoed the stark juxtapositions in Markoe’s remotes.

In the video, a GE security guard approached Letterman aggressively, and later walked up to Hal Gurnee, who had been filming the scene. Both Letterman and Gurnee extended their hands for a handshake, and the security guard started to do the same before having second thoughts, pulling his hand back abruptly. In the editing, Hal Gurnee saw this moment and knew it would make for the key part of the comedy. On the air, after showing the remote piece, Letterman gave this aborted greeting a name: the General Electric Handshake. He smiled when he said it.

Letterman may have become a star celebrated on college campuses and on the covers of magazines, but he still found a way to position himself as an outsider. In turning the network into the unseen antagonist of the show, he found the perfect thing to react against, artistically, at least. As for a career move, mocking your boss has a way of backfiring.

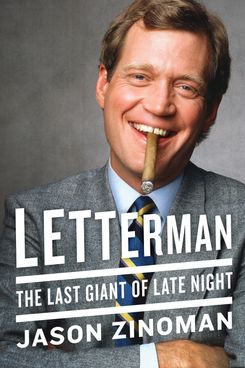

From LETTERMAN: The Last Giant of Late Night by Jason Zinoman. Copyright © 2017 by Jason Zinoman. To be published on April 11, 2017, by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpted by permission.

Top Image: David Letterman performs in New York City circa 1980.