ÔÇ£Unfold your own myth,ÔÇØ blares a graffiti tag on the skin of a subway car in The Get Down. Baz Luhrmann and Stephen Adly GuirgisÔÇÖs 1970s musical melodrama about the birth of hip-hop and the fall of dirty-glorious Gotham is forever characterizing itself this way: like a rapper nimbly reframing a story as he tells it.

What picture are we seeing when we watch this new batch of episodes? ItÔÇÖs a multimedia work: television, movies, a novel, a scrapbook; collage, decoupage, a montage barrage. The Get Down episode guide will likely describe it as part two of season one. But the long hiatus between fresh chapters (tacitly acknowledged by letting the narrative skip slightly forward, from summer to fall of 1977) makes it feel more like a compacted season two. Then again, as is often the case with this show, the best analogies are musical: Think of it as the second of two concert dates in a bandÔÇÖs inaugural tour, the performance where they find their groove and never leave it. Any way you label them, these chapters are a major improvement for a show that was always fascinating, occasionally dazzling, but suffered from a cluttered, even scatterbrained too-muchness, and that often seemed, like its titular crew, to still be finding its style and voice.

No more. A promising show has become a terrific one. The first stage of evolution ended in the final moments of episode six, with hero-narrator Ezekiel (Justice Smith) getting trotted out as a prop at a Bronx rally for would-be mayor Ed Koch (Frank Wood) by South Bronx political boss Francisco ÔÇ£Papa FuerteÔÇØ Cruz (Jimmy Smits), doting uncle of his born-to-be-a-pop-star girlfriend Mylene Cruz (Herizen F. Guardiola). Zeke realized too late that Koch was chasing votes by scapegoating young citizens of color. He seemed to want to bolt, but instead launched into a poetic monologue about the poetry and promise of the streets. ÔÇ£The young people arenÔÇÖt the problem or the solution,ÔÇØ he said, momentarily reclaiming the young voters that Koch had alienated with his rant about the scourge of graffiti artists.

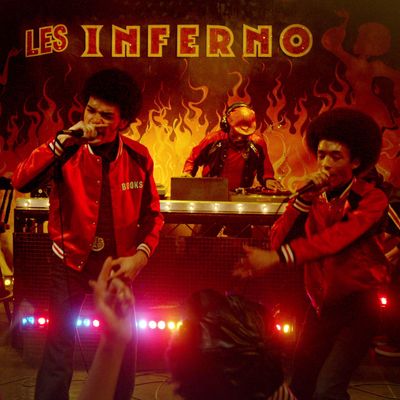

Then he raced off to join a rap battle with his crew, DJ Shaolin Fantastic (Shameik Moore), comic-book artist and closeted gay kid Marcus ÔÇ£DizzeeÔÇØ Kipling (Jaden Smith), his protective older brother Ra-Ra (Skylan Brooks), and his possibly-a-genius kid brother Boo-Boo (T.J. Brown Jr.).

Their triumph was foretold by one of my favorite transitions from 2016 TV: shots of a wrecking ball smashing a condemned building scored to the opening bars of the theme to Star Wars, which segued into a hero-worshiping dolly shot through the Get Down crew as they assembled, John WilliamsÔÇÖs fanfare syncing to ShaolinÔÇÖs backbeat. ThereÔÇÖs a goofily miraculous quality to moments like this, and even when the show got tangled in a subplot spiderweb, it still managed to produce five or six in each episode. TheyÔÇÖre extended cinematic drum breaks, moments when the showÔÇÖs storytelling throws off the shackles of literature and becomes pure visual music, spotlighting a realization or jumping among scenes or subplots like a DJ working multiple turntables. All of the great notions teased out in the first six episodes get shaped and honed to a fare-thee-well in this new batch.

The plot builds organically from the mid-season finale and moves all of the characters forward. ZekeÔÇÖs impromptu stump speech revealed him as a natural-born politician, somebody who might have the moxie and verbosity to build the life he always fantasized about. That proposition is tested in subplots that prep Zeke for college, land him an internship (courtesy of Papa FuerteÔÇÖs largesse) with a prot├®g├® of Robert MosesÔÇÖs (Mr. RobotÔÇÖs Michel Gill). A sequence where Zeke spends the afternoon at his bossÔÇÖ Yale alumni club, engaging proto-yuppies in a drinking contest and absorbing witheringly racist questions, showcases SmithÔÇÖs best acting to date; it also features one of many shamelessly crowd-pleasing punch lines.

Shaolin Fantastic, Sonny Corleone to ZekeÔÇÖs Michael, chases success from the outside ÔÇö or rather from ground level ÔÇö by dealing the demon drug of the Carter era, angel dust. He lets himself get drawn deeper into the syndicate ruled by Fat Annie (Lillias White) and her disco-crazy son Cadillac (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), who hasnÔÇÖt given up on making his only decent song, ÔÇ£Disco Biscuit,ÔÇØ into a bona fide hit, not a novelty single (though you wouldnÔÇÖt know it, the way he tries to position it as a roller-disco anthem). MyleneÔÇÖs career blossoms under the tutelage of her Svengali producer-songwriter Jackie Moreno (Kevin Corrigan), but the suits at Marrakesh Records, led by sleazy impresario Roy Ashton (Eric Bogosian), want her to abandon the godliness she absorbed from her God-fearing mother (Zabryna Guevara) and her Pentecostal preacher dad (Giancarlo Esposito) and become a sequined siren.

There are complications, of course, but as in part one, theyÔÇÖre TV complications that you know will be sorted out soon enough. Shaolin and Zeke have another falling out; Zeke and MyleneÔÇÖs relationship buckles under the strain of her celebrity and his refusal to abandon his crew for even one night; there are betrayals and misunderstandings, devastating setbacks and last-minute 98-yard dashes to victory.

But these stories and others are just sampled pieces in visual-musical tracks that are ultimately more interested in rhythm, atmosphere, and emotion than in validating old-school literary values. The editing leans even harder on stock footage. The gleeful way that the image texture changes from shot to shot (1970s TV news video, 16mm, what looks like enhanced YouTube footage) suggests the filmmakers are glorying in the collage aesthetic instead of knocking themselves out trying to make every piece seem like part of a seamless whole. Pedro Almod├│var once said that itÔÇÖs not enough for a movie to move, it needs to dance. This show dances across the screen. This new chapter adds a second narrator, and with it a second narrative frame, in the form of comic books drawn by Dizzee. These spring to life onscreen in the form of cheeky-grandiose cartoons that suggest underground comics come to life.

The show is never more alive than when it seems to be putting on a show, performing, tossing the spotlight to one character or another, or committing to live inside of choreographed stage performance or a hilariously period-accurate glimpse of a Soul TrainÔÇôlike program hosted by cheeseball horndog ÔÇ£CoolÔÇØ Calvin Moody. Frequent samplings from the film versions and soundtracks to The Wiz and Cabaret liken 1970s New York City to Oz and the Weimar Republic ÔÇö an Eden of decadence starting to be reconfigured by AIDS, crack, and Ronald ReaganÔÇÖs law-and-order mythos.

Dig, if you will, the nimbler way the episodes cross-cut between parallel stories at moments of epiphany for the characters; or the way that music, spoken lyrics/poetry, and voice-over narration glide on top of each other like layers of instrumentation in a song; or the super-fast cutting, which could seem like frenetic wasted motion the last time out, but that increasingly feel an integral part of the showÔÇÖs aesthetic, something that it canÔÇÖt do without, lest The Get Down feel like something other than The Get Down.

The showÔÇÖs rocky start ÔÇö an everything-plus-the-kitchen-sink, Luhrmann-directed pilot followed by three episodes that felt as if the producer and crew said, ÔÇ£LetÔÇÖs all figure out how to do this without killing ourselvesÔÇØ ÔÇö gets slyly acknowledged in the soundtrackÔÇÖs sampling of the Rocky theme, ÔÇ£Gonna Fly Now.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs one of many underdog classics (along with last seasonÔÇÖs Star Wars and the now-ubiquitous Saturday Night Fever) that get sampled, highlighted, and integrated into this tall tale with a pulsing backbeat and a ceaseless flow of visual as well as lyrical rhymes. The series is so audacious now that it can show a character drawing a comic, folding the page into a paper airplane, and throwing it out the window, then have the airplane and the city morph into funky-charming cartoons, and follow the airplane through a window in Rikers Island, confident that we will accept it. And we do.

ÔÇ£Look close, past tragic,ÔÇØ Zeke rapped at the end of season one, ÔÇ£because my home is fuckinÔÇÖ magic.ÔÇØ