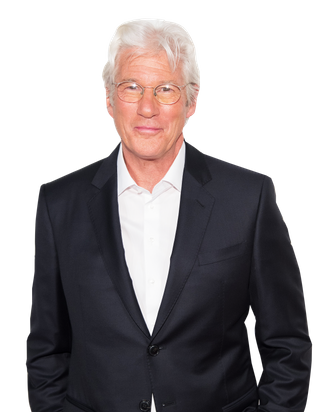

What would you do if you knew your child had committed a heinous act of violence that would land him in prison for the rest of his life, but you had the choice whether to keep it a secret? That’s the question faced by Richard Gere’s character in Oren Moverman’s The Dinner, in which Gere, Rebecca Hall, Steve Coogan, and Laura Linney play two couples whose children took part in an unthinkable crime. Gere couldn’t have been more game to bite. The veteran actor, who’s experiencing a bit of a “Gere-aissance” in the indie-film world, talked to Vulture about why he was particularly drawn to this complex and often unsettling film, what it’s like to play a politician with morals in 2017, and why acting alongside gourmet food and drink is actually overrated.

What most appealed to you about exploring the messy morally gray area where this film lives?

What’s black and white to me doesn’t really exist — except maybe in World War II. That was one of few cases where one suspended all judgment and said, “This is wrong.” But that kind of clarity is very rare. The dialectic that goes one between the four people in this film was fascinating to me. Obviously it’s well-written and well-played by a wonderful cast, but mostly it forces us to ask: What is our responsibility as parents? Not just to them, but to the world?

Your character is a politician, yet he ultimately emerges as the film’s moral center — a bit of a twist considering our current political climate.

That’s what I said to Oren! I said, “Look, I’m doing this film because of my respect for you, but if you want me to play this guy, the way to make it work is to present him as Clintonian — that kind of smiley, charming, wanting everyone to love him kind of politician that we assume has no moral center to them — and then let’s deconstruct that false impression.”

This is your third collaboration with Oren Moverman after Time Out of Mind and more recently, Norman, which he produced. Has a collaborative shorthand emerged between the two of you?

Yes and no, because for this one, we are juggling four points of view. The way the film is constructed, we first see the world through my character’s brother’s eyes, played by Steve Coogan. And that turns out to be a false view as we realize he has mental-health issues and a very colored view of reality. It’s takes the film a while to give us the cues to back off from identifying so much with him.

He’s the narrator, yet we can’t necessarily trust him.

Right. The story reveals his issues, but also everyone else’s. I told Oren from the beginning that the brothers’ relationship really interested me — let’s explore those dynamics. Steve’s character is very vocal in his life, but mine had to be the adult sooner than he ever wanted to be. Everyone was nuts in their family, so he had to be the rational one. I didn’t read the book on which the movie based, but it’s worth mentioning that we invented a lot, too. My congressman character as he exists now in the movie wasn’t in the original script. But it worked because politicians are always working on something. There’s never private time, so it made sense for him to literally be at the table dealing with issues of the government. Remember at one point he says, “Why don’t we make legislation about mental illness?” That’s a plot point that both interested him and fit clearly with Steve’s character. It opened up another possibility of conflict and discussion between us.

This is also your third collaboration with co-star Laura Linney, after Primal Fear and The Mothman Prophecies. Did The Dinner feel like a reunion for the two of you?

Well, let’s first also acknowledge the ensemble as a whole — Steve and Laura of course but also Rebecca Hall. We all wanted to do good work — and this wasn’t a paycheck for anybody. [Laughs.] But Laura is absolutely one of those incredible actresses where there’s very, very little ego. She comes to do the character. And she plays the most difficult character here; you can’t go halfway. Her thought process in the movie is the hardest to defend, so her completely jumping into the character allows us to understand her point of view as the truly human point of view. As a person and an actress, there’s nobody better than Laura.

If I see she is in a movie, there is an immediate comfort knowing that it will be time well-spent.

That’s the way I felt with this whole project. When we first talked about casting, I wanted to know where Oren was going other parts and he asked me about Laura. I said, “If she wants more money, I’ll give it to her!”

The film ends with an abrupt cut to the credits; we never know for sure if any violence has transpired between Steve’s character and your character’s son. What do you think happens?

It’s irrelevant, I think. Did he kill or hurt my son there in the woods? I think it’s best for people to figure that out for themselves

You also have a teenage son in real life. Did the film make you question what you would do in this situation?

Hopefully anyone who watches this movie is going to ask themselves those questions. And if it’s not about your son, it’s your brother, sister, father, a close friend even. When we were doing the rewrites, we improvised a bit on this stuff and I certainly was in the space of, What if it was my own son? With this type of movie, I think it’s really important to personalize it. It has to be completely real and multidimensional, the way one would really feel in this situation.

Compassion and honesty, themes that the movie tackles in their most brutal, raw forms, are both under siege in our country right now. How are you personally working to reconcile this as an artist?

It’s complicated and I’m struggling with it, as I’m sure you are too. In our current situation, one can very easily get extremely angry and confrontational, or totally check out and devolve — give in to the bad guys. And neither of those things unto themselves is going to help anything. Telling the truth and confronting the lie has to be done. Fear and ignorance makes us become smaller. And leaders in this country — and in others, too — are giving the cues to make it alright to be small. But take the Women’s March, right after the inauguration. It was not just in the U.S., but everywhere — Israel, Europe, Asia — and it wasn’t a march of anger. It was one of solidarity, joy, and possibility. That’s the way to move into the future. This is not a time for anger and denouncement. It’s a time reaffirm positive visions with great energy.

It’s worth noting that despite its heaviness, The Dinner also has a clever narrative device: It’s broken up into the courses of a formal, gourmet dinner. Did you actually get to eat or drink any of the delicious food and wine served during filming?

Oren’s a very clever guy — he certainly made his movie the way he wanted to. And we’re talking about doing four or five other things in the future, so I guess you’re going to have to see us together again at some point! But no, truly I can’t remember eating even one bite of food. If you recall, we talked the entire time. Nonstop talking. So we’d pick at the salad or whatever. But there was never a moment when any of us could really eat. Also, it looks a lot better in the movie, frankly, than it did when we were shooting. [Laughs.]

This interview has been edited and condensed.