When Twin Peaks debuted on a Sunday night in April of 1990, critics were already declaring it groundbreaking TV. What they didn’t know was whether the public would embrace this gleefully bizarre blend of murder-mystery, soap opera, and surreal drama. Most Americans had seen whodunit-type TV shows. They had not seen one in which an FBI agent questions a witness that happens to be a log.

Either in spite or because of its brazen freakiness, Twin Peaks became an instant, midseason sensation. Its two-hour pilot won its time slot and was the highest-rated TV movie of the 1989–1990 season, attracting 36 million viewers. The subsequent initial episodes, which, during season one, competed against comedy juggernaut Cheers, also brought in decent ratings. But those ratings declined as time passed, especially during season two, when the show was moved to Saturday nights.

The number of eyeballs glued to each episode of Twin Peaks mattered, but so did the chatter the show inspired. The fan base became obsessive, hosting Peaks viewing parties that turned watching Agent Cooper into a communal experience; parsing the show’s Easter eggs in a time before social media and, for that matter, before anyone used the term Easter egg; and purchasing the inevitable ancillary merchandise inspired by the show. (I can’t be the only one who owns “Diane…”: The Twin Peaks Tapes of Agent Cooper, can I?) Basically, Twin Peaks made us start watching TV the way we routinely watch it in the 21st century, before we had 21st-century tools.

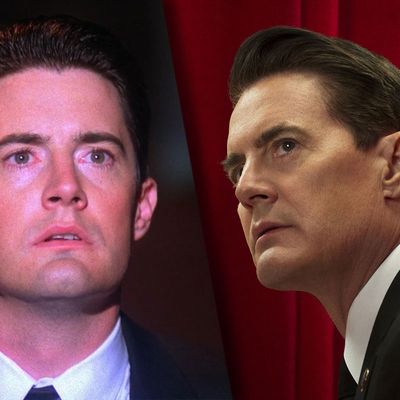

Now that Twin Peaks is returning to television for the first time in 26 years — this Sunday on Showtime, in case you somehow missed the news — one wonders whether the response will follow a similar pattern. While Twin Peaks quickly became a phenomenon and, in the long run, a game changer — its noirish artistry, puzzling plotlines, and off-kilter storytelling set the stage for every ambitious, experimental drama that followed — the series also began to lose portions of its audience almost as quickly as it first attracted them.

When the show ended its second and final season in June of 1991, leaving the air waves “with a whisper,” as a review of the finale in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch put it, it was hard to believe that just a year earlier, Douglas firs and damn fine cups of coffee had been so central to the cultural conversation. “Peaks set a new standard for hot gone cold in a flash,” said a 1991 piece from the Dallas Morning News, picked up by the Chicago Tribune.

Not unlike the revival, the hype for the original Twin Peaks started to build months before it arrived on the air. As Slate noted, the first-ever piece about the series ran in Connoisseur magazine in September of 1989, with the headline: “The Series That Will Change TV Forever.” (Honestly, nearly 30 years later, I still don’t fully read that as hyperbole.) The Washington Post ran a piece that September, too, in which critic Tom Shales, who had seen an early screening of the two-hour pilot, wrote this: “Twin Peaks isn’t just a visit to another town; it’s a visit to another planet. Maybe it will go down in history as a brief and brave experiment. But as can be said of few other TV shows in the near or immediate future: This You Gotta See.”

The subsequent walk-up pieces and mostly positive reviews said some version of that same thing: “Nothing like it has ever been seen on network television.” (That particular comment appeared in the New York Times.) So seriously was Twin Peaks taken that even The New Yorker, which, according to a USA Today article at the time, hadn’t reviewed a TV show since 1982, published a take on the series in the Current Cinema section, usually reserved for film reviews. “[David] Lynch’s talent flows freely in Twin Peaks and carries us into unmapped territory,” wrote Terrence Rafferty. “It’s an exhilarating ride, at once scary and mysteriously tranquil, like the children’s nighttime journey in The Night of the Hunter.”

While there were a few less-than-enthralled critics — John Voorhees of the Seattle Times said he “didn’t much like it or find the characters terribly believable” — the prevailing sense was that Twin Peaks was an event, as opposed to a mere midseason replacement, an idea ABC seized upon in its marketing.

But despite the enthusiam, the people at ABC, critics, and other media observers were not necessarily confident that American audiences would be eager to ride wherever David Lynch’s stream of consciousness took them. “I don’t think it has a chance of succeeding,” media analyst and ad executive Paul Schulman told USA Today prior to the show’s debut. “It is not commercial, it is radically different from what we as viewers are accustomed to seeing, there’s no one in the show to root for.” A New York Times Magazine profile of Lynch also published before the Twin Peaks premiere noted that: “Executives at ABC have only a vague idea how America will react to this eerie, experimental soap opera. ‘We did a cable test that was pretty positive,’ says Gary Levine. ‘Not overwhelming, but positive.’” Then the pilot aired, won its time slot, and became the fifth most-watched program of that week.

Levine, at ABC back then, is now the president of programming at Showtime, where he’s been one of the key individuals responsible for bringing the show back to TV. Just as ABC did back in 1990, Showtime has been hyping the new Twin Peaks as something that cannot be missed. In a way, even though the television landscape is far more crowded now, the premium cable network should face a less daunting marketing challenge than ABC did because they’re pushing a known product. Those who lived through the Peaks mania of the early ’90s as well as those who, understanding its influence, discovered it on DVD, Netflix, or Hulu, know what Twin Peaks is in a way that viewers in 1990 did not.

Yet potential Peaks viewers in 2017 are also more in the dark than ever. Where advance media coverage of the first iteration made it clear what the show was about — a homecoming queen murdered in a small town and an attempt to find her killer, a premise destined to attract interest since America loves its crime shows — the onslaught of Peaks coverage that has led up to Sunday has purposefully been — whispers in dancing dream-sequence little-person voice — “filled with secrets.” We know who’s in the new Twin Peaks (most of the original cast as well as one-quarter of SAG’s membership). We know David Lynch and Mark Frost collaborated on the project and that Lynch directed all the episodes. We know, per Variety, that Laura Dern will appear in scenes with Kyle MacLachlan and talk about birds, “at least once.” But that’s about it. No episodes are being released in advance, which means no reviews insisting, “this you gotta see” will be out there ahead of time either.

The combination of nostalgia and curiosity may be enough to bring viewers to Showtime on Sunday night, just as the intrigue of the Twin Peaks pilot attracted 36 million viewers to ABC on a Sunday night almost 30 years ago. The question is, will it be enough to keep them there for the full run of 18 episodes?

While the importance and legacy of Twin Peaks are both undeniable, the show’s ability to attract a mass audience did falter. What may have curtailed the show’s reach more than anything was a lack of direction following the reveal of Laura’s killer combined with a lack of patience from viewers, especially those primarily interested in resolving the central mystery rather than soaking up the atmospherics and llama improv. While sifting through old articles from the spring of 1990, I was stunned to recall the extent to which people instantly expected to find out who killed Sheryl Lee’s character. Tony Kornheiser — in his pre–Pardon the Interruption Days, when he covered sports but also wrote a column for the Post’s Style section — suggested that frustration was already seeping in before the damn two-hour pilot was even over. “‘Twin Peaks’ is not for the casual viewer,” he wrote. (“A friend who tuned out with 30 minutes to go wondered, ‘Who killed the girl?’ I told him at this pace we might not know for five years.”) He also said that the ensemble drama had so many characters that “if it runs long enough, we’ll all be on it.” Which kind of feels true of the revival?

Audiences today are far more willing to let story lines play out, and I’d argue part of the reason that they are is because Twin Peaks and the shows that followed in its footsteps have conditioned audiences to accept stories that breathe. But in other ways, we’re also less patient. With so many other dramas and comedies immediately available to binge, there’s more pressure than ever on TV shows to immediately command our attention. When Twin Peaks debuted in 1990, it was the only truly daring series on television at the time. When Twin Peaks returns on Sunday, it will be on opposite two other premium cable series — HBO’s The Leftovers and Starz’s American Gods — that could easily beat, or at least tie, Twin Peaks in a Weird TV Olympics. The expectations it has to meet are high, to an almost unfair degree.

When the final episode of the first Twin Peaks aired, about 10 million people tuned in, which would be a damn fine number in 2017, but felt fairly anemic in 1991. Ed Bark, the Dallas Morning News critic, wrote a review of that finale that doubled as an obituary for the show: “Last year at this time, ‘Peaks’ had cornered the market on major cool. Creators David Lynch and Mark Frost were the Highnesses of Hip, dispensing their wondrous wisdom to immersed, impressed TV critics. But ‘Peaks’ ” architects soon fell victim to their own cosmic conceits, treating viewers as string-along puppets willing to buy any contrivance.”

“But there may be better times,” he added. “Perhaps the future will be kinder to ‘Peaks,’ making it a ‘Batman’ or a ‘Monkees’ of the 21st Century,” referring to the fact that both of those silly shows experienced a new renaissance in popularity two decades after they originally aired.

The years between 1991 and 2017 have definitely been kind to Peaks, more than Bark could have even imagined. Starting this weekend, we’ll find out how kind the audience is to a new Twin Peaks, how experimental Lynch and Frost have decided to go, and just how willing today’s more sophisticated viewers are to let a mystery — or multiple mysteries — be.