During the past three years, Louisville native Bryson Tiller’s quiet but inexorable emergence into one of the best, most popular young stars of R&B has always been accompanied by some degree of confusion from more cynical observers as to what, exactly, is so special about him. It wasn’t as if blending rap and soul together hadn’t been on other artists’ agenda before him after all, and he was far from the only artist, in the wake of Drake’s success, to focus, in song and in spoken words, on mundane relationship issues. In a time when most rising stars had hitched themselves to designer labels, Tiller refrained from dressing flashy, preferring quiet attire conveying an air of self-sufficient economy.

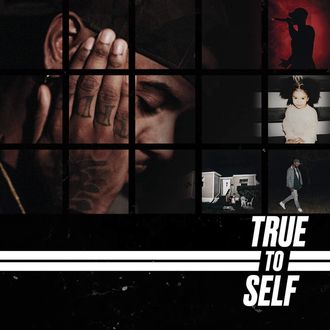

Tiller’s personality seemed to be that he didn’t make too much of a deal about personality. Keeping his circle tight, he made his songs, trusting that the message would get through on its own. It was a faith verified by experience: The success of his debut album Trapsoul (2015) was achieved with very little boosting from the music press. Tiller, who had gone from sleeping in his car and borrowing money from friends to make the SoundCloud track (“Don’t”) that launched his career, found himself, barely in his 20s, rich and welcomed by the black musical elite he’d looked up to. Collaborations in 2016 with the Weeknd, Future, DJ Khaled, and Travis Scott confirmed his status without quite casting light on why and how he had attained it. Released suddenly last Thursday, Tiller’s sophomore LP True to Self offers a chance to clarify just what, exactly, is going on.

His nondescript nature likely has much to do with a city of origin whose character is equally hard to explain from the outside. Though populous (roughly a million inhabitants) and old — founded in 1778 during the Revolution, it’s named after the French monarch who bankrolled the insurgents — the size and age of Kentucky’s largest city hasn’t made it any easier to define. Much as Tiller belongs to two genres at once, the culture of Louisville, perched on the south bank of the Ohio, combines elements of the Midwest and the South, though it is, in the end, more Southern than not. (Prior to the Civil War, it was a key node in the slave trade.)

If Tiller, in his lyrics, navigated through uncertain interpersonal transitions, his hometown, located at the site of a waterfall that forced settlers to disembark from their downriver boats to stop and shop, later ideally placed to ship goods by air (UPS, where Tiller once worked, has a hub there), was literally built on being in between. Louisville is, essentially, a place where people stop, look around, decide that what they have is good enough, and settle. The self that Tiller, whose new collection traces, haltingly, a renewed commitment to the mother of his daughter, is being true to is as much his city’s as his own. Louisville is the biggest small town, a fact mirrored by its status as the biggest television market for college sports and its lack of major league teams.

For better or worse, normality prevails. Though the city produced two scandalous, exceptionally outspoken figures — Hunter S. Thompson and Muhammad Ali — during the ’60s and ’70s, the most recent Louisville native to become a household name (Jennifer Lawrence) did so by projecting an aura that raises the normal to an exceptional level. If the gap between Lawrence’s East End background and Tiller’s Southside experience bear witness to the city’s continuity with national divisions of race and class, the similarity in their affect testifies to something particular about their home city and its devotion to the ordinary.

All this is to say that anyone expecting True to Self to mark a drastic shift in tone or sound was going to be mistaken. Tiller, whose solidly constructed tracks prioritize staying power over immediate impact — Trapsoul went platinum not by topping the charts in its first week but by hanging in the top 25 for half a year — had made a name off of being consistent. As the collection’s title suggests, there’s no need to greatly change up a sound that’s still fresh and durable. Though the producer roster on True to Self is totally different than that of Trapsoul (the new album is a coming-out party for the producer NES, a Bowling Green, Kentucky, native who was working in an auto plant when he emailed Tiller some instrumentals), the production itself is very much of a piece with the cozy and submerged aesthetic established by its predecessor. And fittingly for the artist who made “The Sequence” on Trapsoul, the sequencing on True to Self is equally fluent as on its predecessor.

There are some adjustments, though: There’s more of a plot now, though it’s not exactly easy to follow. For Tiller, keeping faith with self means keeping faith with the past: the process of renewing his pledge to his daughter’s mother involves recounting the just-friends-until-not origins of the romance and its troubled progress before it can conclude on a note of commitment. It’s not an easy relationship, and its story isn’t easy to follow, especially when it’s further punctuated by songs (“Blowing Smoke,” “Self-Made,” “High Stakes,” “Money Problems / Benz Truck,” “Before You Judge”) focused on his new wealth and status and the by-now classic troubles — old friends gone sour, seductive new women — that accompany it. The new album is more pressurized and less of a relief than the old, but it rewards relistening more. Tiller’s still, essentially, the guy that’s there for you, but being there is harder than it used to be, and though he maintains a calm demeanor, he has more cause and opportunity to cut loose than before: “I’m bout to go Kanye West on niggas / You know, care less if I upset some niggas,” he snaps on “Money Problems / Benz Truck”; that track, along with “You Got It” and “Self-Made,” are points of immediate engagement whose dynamism will tide one over as the charms of the rest of the album sink in more slowly.

Whether one loves it, hates it, or is lukewarm toward it, True to Self feels like a long-term thing. Who knows if the relationship Tiller describes on it will last (I think it will) but there’s no doubt that he’s already married to the patiently driven and quietly potent sound he’s developed. The new LP won’t change anyone’s opinions about him — if you think he’s mild sauce, you’ll still think that, and if you think he finds the brilliance in the mundane, you’ll still think that. Being raised in Louisville myself, there’s no way that I can’t fall squarely in the latter camp. Being the steady one, or even just claiming to be, gets the job done. Even the most jaded should still respect the game, if only on grounds of efficiency: Tiller’s as real as it gets, but no less of an authority on New York cynicism than Seinfeld will readily concede that “That ‘there for you’ crap is a stroke of genius.”