With today’s new Long Strange Trip, producer Martin Scorsese, director Amir Bar-Lev, and Amazon Studios have finally crafted the definitive Grateful Dead documentary. Others have tried: 2014’s affecting The Other One: The Long, Strange Trip of Bob Weir and 1977’s hokey, self-directed The Grateful Dead Movie both captured pieces of the story. Countless concert tapes bore witness to the band’s radical, improvised psychedelic blues. But the new film trumps its predecessors in both method and scope. In assuming the loose expanse of the Dead’s live shows as its structure, it barrels along just as stoned and free as its subjects. It’s four-hours long and split up into six chapters, the same way Dead shows were divided into themed sets. The “Drums > Space” section tries to get you to dissociate. You might cry during “Brokedown Palace.”

Long Strange Trip splits the difference between your typical talking-head documentary and a mix of trippy visuals, career-spanning show footage, and home movies. The pool of source material is impressively vast, since the Dead rank high among the most meticulously documented musical acts of all time. The wealth of juicy archival footage ultimately tells two stories. The journey of the Dead mirrors that of ’60s counterculture in miniature: It exploded in San Francisco, skipped town when the Haight got too hot, nearly lost itself in the druggy excess of the ’70s, and enjoyed a reappraisal in the ’80s thanks to the birth of the classic-rock radio format and a new generation anxious to tune in and turn on.

The band’s triumphs and struggles have never been so soulfully rendered on-camera, which makes this essential viewing for diehards. Lifers and collectors get rarities like disorienting footage from an aborted early-’70s Dead doc deliberately sabotaged when the band dosed the crew with acid, and the cameramen proceeded to film their own trip instead of capturing their subjects’ experiences on tour in Europe. Warner had hoped to turn the trip into a career-boosting classic-rock doc. They meant well but never quite knew what to do with the band, and it’s a frequent point of comedy throughout early chapters. The official soundtrack digs up ephemera like a 1970 run through the Live/Dead centerpiece and live-show juggernaut “Dark Star.” (The funniest moment in a documentary peppered with cracked laugh-out-loud moments comes when the crew goes on a quest to figure out what the song’s inscrutable poetry even means.)

Long Strange Trip is also accessible for newcomers. It smartly catalogues epochal shifts in the Dead’s relationship to both the recording industry and the American counterculture, from confounding labels and audiences alike in the acid tests with Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters in the ’60s to struggling to control the ticketless masses holding tailgate parties outside the sold-out stadium shows of the ’90s. Superfan Senator Al Franken explains the finer points of tape collecting, fixating on nuances in guitar solos across different performances of the same song. Everyone involved recalls their time in or around the band with the warmth and detail of a fondly remembered acid trip. The only thing the Dead did better than music was to make sure that everyone in its path got or at least felt stunningly high.

Long Strange Trip finds the surviving band members nostalgic and charmingly offbeat. Singer and rhythm guitarist Bob Weir gives his main interview in a half-lotus pose on top of a pillow in the top floor of a rustic vista. We find percussionist Mickey Hart in a studio describing the drums as instruments of time travel. Weir’s songwriting buddy John Perry Barlow is introduced on a drive to the final resting place of deceased founding Dead member Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, where he recoils at the sight of guitar picks fans have left on a keyboard player’s gravestone.

The most colorful characters in the documentary are holdovers from the Dead’s traveling detail of staff, friends, roadies, and management. Early ’70s tour manager Sam Cutler punctuates the prevailing fondness for the band’s 1970 folk period with hard facts about the era’s astounding shortsightedness: “The Grateful Dead are dumb … They make fabulous music, wonderful, amazing music … When it came to business decisions, stupid.” The band’s entourage ballooned with hangers-on who were allowed to have a say in business deals. We learn that the Dead’s titanic, Owsley-designed “wall of sound” speaker rig took four hours to set up and bust down, meaning audiences got perfect sound, but roadies got no sleep.

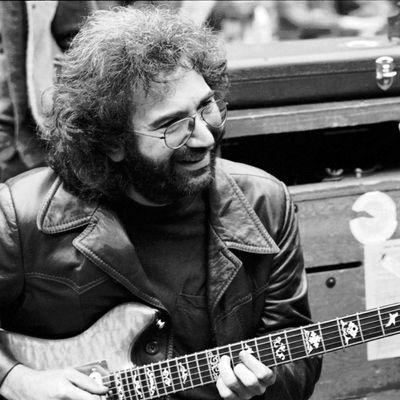

The Grateful Dead’s unbreakable commitment to flux and motion was the spark that first shot it out into the lunatic fringe of the ’60s, but those same devotions laid the latticework for its undoing. Early on, Jerry Garcia’s reluctance to take charge as front man was a gift and a curse; the lack of top-down leadership kept the Dead inclusive and unpredictable, but unpredictability sometimes made it unmanageable. When the band became a stadium-grade touring operation, Jerry buckled under the weight of responsibility for both his crew’s financial well-being and the happiness of tens of thousands of fans. Suddenly, a band designed to sidestep responsibilities had become a crushing obligation of its own. Garcia began as the reluctant, de facto focal point of the band’s energy but grew wan and weary as it lingered. He burned out, and everyone knew it; the Dead’s faith in his enduring resilience proved as destructive as any of the bad drugs that ensnared him.

The central paradox of the film is one that has plagued the band for decades: How can this thing that brings people so much joy have caused so much trouble for everyone close to it? In its detailed examinations of unlikely successes and grisly fates, Long Strange Trip offers an answer: The price for constant motion is wear. The human body is not built to sustain it, though the mind is game to try. The Grateful Dead spent 30 years in an elaborate dance with death and stardom, and discovered creative methods of evading both for years. But when the band’s demons cornered it in the mid-’90s, it was woefully unprepared to do the only thing that could save it, to cease to exist. “The secret of longevity in the music business,” a tanned and beaming Cutler wisely notes near the end of the film’s final chapter, “is to get away from it. You gotta leave it, man. Fuck off.”