There are many excellent jokes in Okja, Bong Joon-ho’s genre-mashing movie about the titular GMO super-pig and its kid caretaker Mija, which is now streaming on Netflix. There are poop jokes; there are Tilda Swinton’s braces; there are references that run the high-low gamut, including a re-creation of the Obama war-room photo and Andrew Lincoln’s poster-board confessional from Love Actually. But there’s another joke buried in the subtitles, a little gem reserved for that special group of people who can speak both Korean and English.

The moment happens when the radical animal-rights group ALF (the Animal Liberation Front), headed by Jay (Paul Dano), ostensibly rescues Okja from the Mirando corporation. But what they’re really trying to do is use Okja as a mole to expose Mirando’s animal-rights abuses. To do this, they would have to hack into Okja’s monitoring system and allow the super-pig to be taken back to the lab. Jay won’t go through with the plan without Mija’s (Ahn Seo-hyun) consent, but the only way to communicate with her is through fellow ALF member K, a Korean-American character played by Steven Yeun. When they ask Mija what she wants to do, she says that all she wants is to go back to the mountains with Okja, but K lies and says that she agrees to the plan, much to the delight of his comrades.

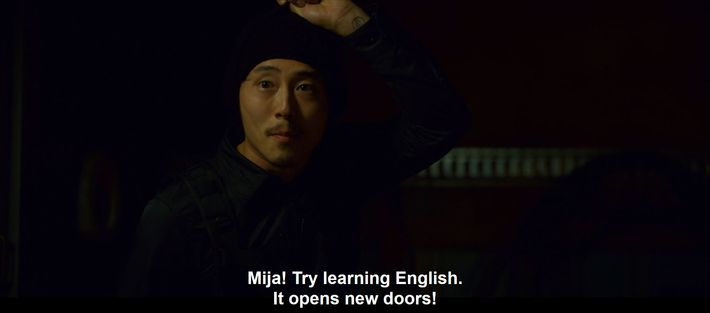

With that, each ALF member jumps out of the truck into the Han River below, with K the last to go. According to the subtitles, his parting words to Mija are “Mija! Try learning English. It opens new doors!” In an earlier version I watched, the subtitle read, “How’s my Korean?” What he actually says is “Mija! Also, my name is Koo Soon-bum.”

It’s a flagrant mistranslation — but one that would only be apparent to those who can speak both languages. Moreover, the mistranslation is a clever subversion of the supremacy of English. The subtitle is a command to learn English — something that every Korean student has heard throughout her life — but to actually understand what K is saying, you would have to know Korean. There’s an added layer of comedy to the name itself, which has the whiff of the old country about it: “Koo Soon-bum” is sort of like a white man saying his name is “Buford Attaway.” As Yeun told me, “When he says ‘Koo Soon-bum,’ it’s funny to you if you’re Korean, because that’s a dumb name. There’s no way to translate that. That’s like, the comedy drop-off, the chasm between countries.”

Bong wrote the character of K specifically with Yeun in mind, because he’s a character that only a Korean-American could play. Yeun’s performance itself is a nod to that gap; it reads differently if you know Korean. While it’s obvious that he’s a bit of a dolt, if you have the ear for the language, his failures are more apparent, because he speaks with the stiltedness of a second-generation speaker (Yeun’s actual pronunciation is a lot better). He’s not quite sure of himself, and is trying to fit into both spaces, but can’t. (This is also why the other subtitle joke that I saw, “How’s my Korean?” works in a subtler way.) Yeun said the character “speaks to the island we live on”: He was a character written for Korean-Americans.

Throughout Okja, Bong plays with the idea of translation, both its necessities and inherent limitations, and the inevitable comedy that arises out of that space. When Jay learns that K deliberately lied, he starts to beat him up, telling him to “never mistranslate!” Toward the end of the movie, K pops back up with a fresh tattoo that reads, “Translations are sacred.”

Part of what makes Okja so remarkable is that Bong Joon-ho has found ways to make jokes that track across both cultural spheres. Unlike the wave of male Korean directors who crossed over into Hollywood around the same time, Park Chan-wook on Stoker or Kim Jee-woon with The Last Stand, Bong never let go of his roots. He cast Korean actors Song Kang-ho and Ko Ah-sung and had them speaking Korean dialogue alongside Hollywood stars Chris Evans and Octavia Spencer in his dystopian train ride thriller Snowpiercer. He furthers the Korean-American dynamic in Okja, centering on a young Korean girl and pitting her against the forces of an American corporation headed by Tilda Swinton’s knobby-kneed CEO. Just as the dialogue shifts seamlessly between both languages, Bong easily trots around the world, from the Korean countryside dotted with persimmon trees to the underground shopping malls of Seoul to the streets of New York City.

“Director Bong is probably one of the few, if not the only, people I’ve seen so far, that’s been able to bridge the two together,” said Yeun. “I don’t mean being able to do an American movie — a lot of directors could probably do that — but bridging the two cultures together in a cohesive way. That’s a tall order, and somehow, he accomplishes that.”