There’s a story in Ear Hustle’s third episode that encapsulates much of what makes the podcast utterly fascinating. The man who tells it is a character you might find in just about any environment that packs different people into the same place over an extended period of time: high schools, offices, summer camps, the many milieus of Richard Linklater movies. But in this case, the environment in question is San Quentin, a California state prison located just north of San Francisco. The man’s name is Rauch, and he’s described as an animal lover who is often found barefoot and sketching in a part of the prison yard called Hippie Row. He speaks slowly, as if in a daydream. The story he tells is about a frog.

“Everywhere I moved in the cell, it would move somewhere to watch me,” Rauch explains. “I would move over here and get out of view, and he’d come up to look at me. I think he was letting me know that, ‘You know what? You go to sleep, and I’m gonna pee on you, dude.’ So I ended up letting him go.”

It’s a moment of levity in a setting often described in the worst of terms, a productive kind of conversation between the specificities of a person and the overpowering context of his incarceration. That, in a nutshell, is the juxtaposition that defines Ear Hustle.

The podcast keeps its attention solely on the immediate experiences of the people who are living their life within those prison walls, and it mostly keeps the bigger picture out of its concerns. It doesn’t speak about the policies and structures of the prison-industrial complex. It does not seek to contextualize the incarcerated individuals in terms of statistics or populations, or even in relation to larger society. Ear Hustle keeps the focus tightly on each individual, parsing out their stories as they range from the banal (an antagonistic pet) to the extreme (a hunger strike to change solitary-confinement policies).

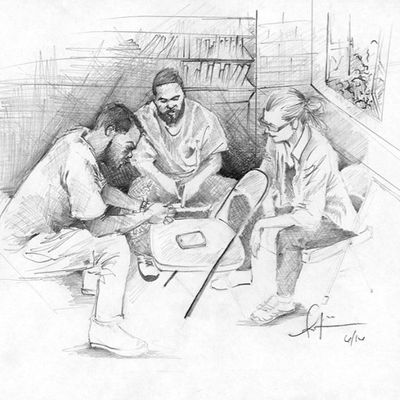

Ear Hustle is a collaboration between Earlonne Woods and Antwan Williams, both of whom are inmates at San Quentin, and Nigel Poor, a Bay Area visual artist. Woods and Poor co-host each episode with Williams co-producing as sound designer, and the insider-outsider structure is an invaluable contribution to the show’s larger narratives about San Quentin.

Most prison stories, as they exist in the larger culture at this point in time, are rightfully critiqued for being told from an outsider’s point of view. There’s a structural deficiency to this approach, because the best it could ever achieve is a detached intellectual understanding of the prison system and its consequences. Ear Hustle puts the opposing solution in practice: Woods and Williams not only define the language and perspectives of the stories being told, but they also retain ownership of them. These things matter, and nowhere is this more apparent than when an episode delivers true and hard detail. “Prison does different things to different people. Some guys are the same guys that walked in here years ago, they just older. It’s like they’re frozen in time, suspended animation or something,” Woods says in the second episode. “Other guys, they change. They go through all the groups and all the shit and they think about what they’ve done.”

Poor also plays a crucial and curious role. To say that she functions as ambassador or a translator of some sort — or even a “bridge to the outside world” — would be inaccurate, not simply because the description runs the risk of being reductive or dismissive of the agency that Woods and Williams possess in these episodes. It’s also not what she’s doing: Poor’s presence as an outsider does allow for key narrative housekeeping, filling in salient factual and emotional details, but her perspective is an active one and her specific viewpoints have an propulsive effect on the show’s feel. “It’s like a village,” she observes in the episode about inmates and pets, which doubles as an exploration of the human desire to nurture. It’s a bit of a strange thing to say, but it’s still illuminating.

Ear Hustle is the latest full-time addition to Radiotopia, the podcast collective operated by Boston-based PRX that’s home to a number of well-loved shows: 99% Invisible, The Heart, Criminal, Song Exploder, and Fugitive Waves, among others. The show also arrives with quite the pedigree, as the winner PRX’s inaugural Podquest competition last year — a sort of American Idol for podcasts, to put it crassly — where it beat out more than 1,500 entries from around the world.

The win is well-deserved, in part because Ear Hustle is a very good match for Radiotopia. Independent, idiosyncratic, and rebellious, Radiotopia shows tend to embrace their smallness and often punch way above their weight. Ear Hustle lands well within those traditions. Nevertheless, some things about the show are unprecedented for the podcast collective: The sociological stakes are unambiguously bigger, the stories feel more urgent. You’re not only listening to small, intimate stories; you’re also listening to palpable, piercing descriptions of the sustained violence that our system commits to human bodies.