Saturday in the Hamptons, the hedgerows are trimmed, the hydrangeas are bushy, and the sun is at peak performance. Outside Jack’s Stir Brew Coffee in Amagansett, a group of men and women in luxury sportswear are gathered, and the air fills with the soothing sound of high-end gossip. Chappaqua … We stayed there … His first wife … Adirondack chairs … The best … Chappaqua.

But all is not right with the world, one is reminded, as a new figure trudges up the path. It’s Alec Baldwin, clad in a navy-blue blazer, a grim look on his face. The smooth jazz of conversation slows, then stops.

As in the city, the unspoken rule out here is that celebrities are to be left alone, but as Baldwin approaches the door, one of the women leans over and addresses him with profound urgency. “Saturday Night Live,” she blurts wildly. “It needs to come back early. We need you!”

An eternal second passes as everyone registers the breach of protocol. Probably it will be okay, they hope. Out here, Baldwin isn’t a celebrity. He’s one of them. A figure in the community. A player of charity softball games, an actor in local theater productions, a supporter of Guild Hall and other area cultural institutions. This very night, in fact, he’s attending an event for the Hamptons International Film Festival, a cocktail party and screening for Trophy, a documentary about lion and rhinoceros hunting. (Baldwin is actually a festival co-chair, and has been on the board for nine years. He’ll be moderating a talk with the directors after the film.) Then again, he is also known for his irascibility, especially when it comes to his privacy. He once wrote a letter to the local paper decrying “vermin” who “casually invade the privacy of people out in public” by taking constant photos. At 59, he’s not unlike a rhino: cute from a distance, but up close, prone to goring.

Not today. Baldwin manages a half-smile and a nod before beelining into the coffee shop. This is something he gets a lot, he says as he studies the bagel selection, people imploring him to impersonate Trump like it’s his patriotic duty, especially these days, with Saturday Night Live on hiatus and the world where Donald Trump is president maddeningly continuing to spin. “It’s a narcotic for people,” he says. “Not just me but anyone who does anything that mocks Trump. It kind of assuages their fear and anxiety.”

Baldwin’s tone suggests he may not entirely approve of this kind of soporific indulgence. “The amusement factor, that’s gone now,” he says sorrowfully as he moves down the line, bagel in hand. They’re out of lox; he opted for the Mediterranean tuna salad.

“It’s just a nightmare, a living nightmare.” At the register, Baldwin picks up a paleo cookie. “He’s like a guy who is, like, ‘I would rather crash the plane into the ground than have the wrong people get their hands on it,’ ” he says of Trump. “It’s like a suicide mission, but the government is the vehicle.” He grabs a second paleo cookie. Why not? We’re all going to die anyway.

Baldwin has threatened to quit playing Trump in the past, citing, among other things, the physical toll the lip-puckering has taken. But he’s signed up to make several appearances this fall season. It’s a “yuge success,” he says. (He’s also writing — with Kurt Andersen, former editor of Spy — a satirical book in the voice of Trump.)

Plus, he points out once we’re seated at a picnic table, he doesn’t have to dig deep into his bag of acting tools. “It’s not some finely etched rendering,” he says. “It’s like a Patrick Oliphant or Barry Blitt caricature.” It’s the kind of reference you might make if you were doing a caricature of Alec Baldwin.

Given his antipathy for the 45th president, it feels awkward to mention it, but one reason Baldwin might find it easy to slip into the soul of Trump is that they have a lot in common, starting with their pronunciation of the word yuge. Two New Yorkers who found success in Manhattan in the ’80s and became creatures of tabloids, thanks to their marriages to and messy divorces from glamorous blondes. Like Trump, Baldwin is a blusterer, a brawler, whose willingness to take on even the puniest of enemies (he recently got into it on Twitter with, as he put it, a “bitter and obscure” Trump impersonator). He seems to feel perpetually misunderstood, particularly by The Media, which on the whole adores him but to his mind invariably fails to treat him with respect. I end up mumbling something about how Baldwin must have an understanding of Trump’s milieu. Manhattan is a small island; the one they reside in is even smaller.

But according to Baldwin, they barely interacted. “No one knew him,” he says, tearing open a paleo cookie. “I always say Trump survived in New York because no one was close to him. He was never a dinner guest; he was never a tablemate. You never sat down and talked to Trump about what was on his mind. He was a drive-by figure. He had the tux on, photo, photo, photo. Then he was gone. And he could do that, because making money in New York matters.”

He’s animated. “Many people I know feel with Trump that something is wrong with him neurologically, psychologically. That may be so. But I think more than anything, he doesn’t think things through. He ran for president out of spite, and he won because it’s rigged. And now he’s miserable.” He unwraps the second cookie. “Now people spit on him and mock him, and his supporters are not his crowd. What is he going to do, go to a barbecue in West Virginia every day with a bunch of unemployed people?”

Over the years, Baldwin has threatened to run for various political offices, but it hasn’t happened. In his memoir, which came out this spring, he suggests that shame over some of his behavior — specifically, an audio recording of a nasty voice-mail he left his older daughter, leaked to the press in 2007 by, he claimed, his ex-wife and her lawyer — may have been a reason.

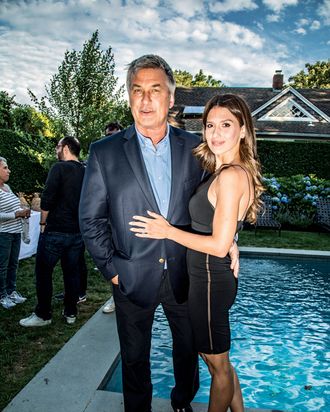

Now that recent events have indicated unflattering leaked audio recordings are no barrier to the highest office in the land, will he change his mind? “I’d consider it if I thought I’d win,” he says. “But I think Trump is going to slam the door on nontraditional candidates.” A bigger obstacle is his new family. Like Trump, Baldwin ended up marrying a younger brunette, Hilaria, a now-33-year-old yoga instructor with whom he has three children under the age of 4. “She has already told me she doesn’t want to put our kids through that,” he says.

His phone buzzes. Hilaria’s picture appears on FaceTime, and while I can’t be positive, I think I see Baldwin sneak the cookie wrapper off the table before answering. They make arrangements to pick her up for the Film Festival event, where most people, he expects, will want to talk to him about Trump. “I don’t think he’s going to make it till the end of the year. I think he can’t take the ridicule. I think he’ll resign.”

Come fall, he’ll be doing his part to make that happen, but to his fans, it’s not nearly soon enough. At the party that night, I see a woman approach him. “I’m really glad to see you,” she says. “But I wish you were on Saturday Night Live tonight.”

*This article appears in the August 7, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.