From TV to books to movies, dystopian tales are in the air right now. All week long, Vulture is exploring how dystopias have been imagined in popular culture.

Imagine yourself in a dystopian future. Maybe you’re one of the thousands of proles living out what can barely be defined as a life, hiding out from murderous robots/dragons/mutants/the upper class. Maybe you’re a member of that oppressive class, or a robot/dragon/mutant. The important thing is that somehow you’ve gotten access to a TV screen. Bad news: It’s ugly.

When people imagine the future, they can be pretty good at coming up with wild and crazy big ideas. The trouble, however, is that they don’t anticipate how our own reality might change, and change quickly, before those big changes arrive. This is a long way of saying that most dystopian movies feature technology that seems outdated, even if that technology’s used in ways that are far beyond what we can do today. In other words, most dystopian TVs and screen interfaces look terrible.

Let’s start your journey with 1982’s Blade Runner, where the screens available are primarily found on giant building-sized advertisements (that’s gonna produce a lot of neck pain) or the dinky Voight-Kampff machine Deckard uses to interrogate various potential replicants. Surely there are other screens available in 2019 Los Angeles, but if they’re all as grainy and washed out as these, then it’s gonna be hell to watch the last season of Game of Thrones.

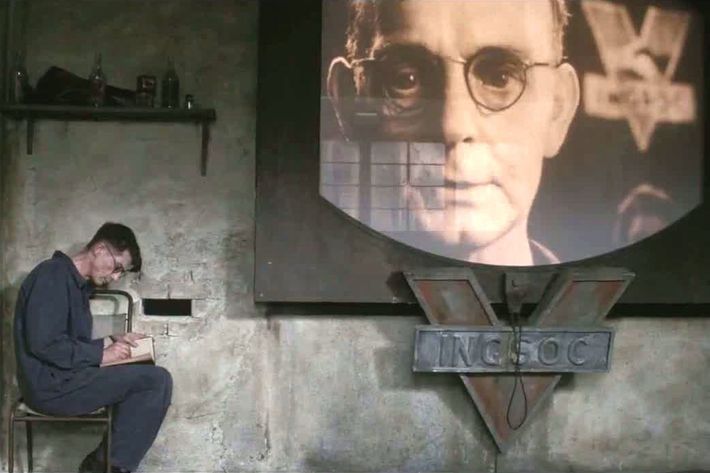

In 1984 (released in 1984), Big Brother is always watching from various eye-catching setups that are nevertheless difficult to fit into your home, and not all that colorful. I assume that the torture of living in 1984’s dystopia comes primarily from all the torture that takes place, but secondarily, it probably comes from trying to develop good feng shui around all these behemoth TVs.

Brazil’s screens are actually fairly advanced for your average dystopia — look, they’re pretty flat! — but the resolution’s pretty terrible, and there’s so much distortion. Plus, the odd magnified format reminds us of those terrible projection devices they would sometimes use to write on sex-ed slides in marker in middle school. Pass.

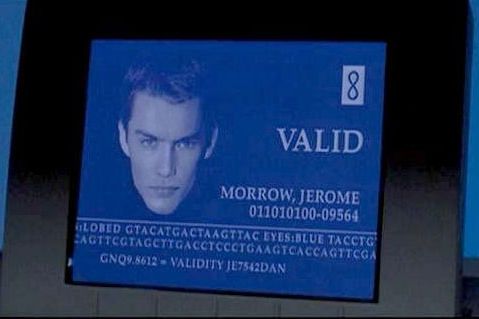

Gattaca, released in 1997, is very fond of the early Windows blue-screen aesthetic in its computers, which is an anomaly for a society so obsessed with genetically perfect people. To make matters worse, their treadmills don’t even face TV screens, which makes you wonder how any of these people get themselves to spend time at the gym.

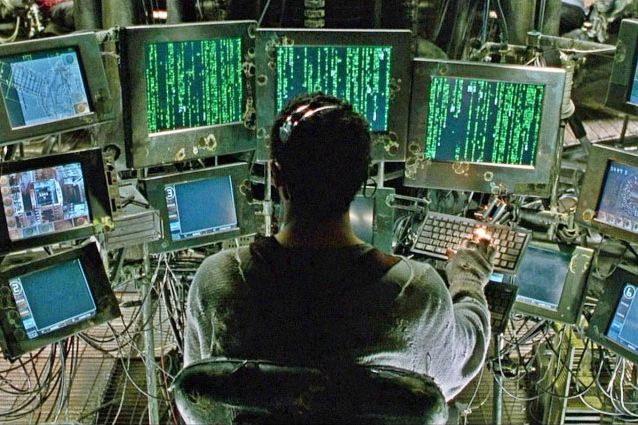

In the future, The Matrix predicts that instead of better screens, we will simply have more of them. In a way, this is something akin to second-screen viewing.

By the 2000s, we get to films like Minority Report, which have some pretty appealing interfaces that you navigate in unconventional ways. Here, Tom Cruise has to use all sorts of hand gestures to track people down, which sounds awesome and cool, until you have to deal with something like a Wii remote and the whole enterprise feels exhausting.

Say what you will about V for Vendetta’s awful U.K. regime, they figured out some crisp TV resolution.

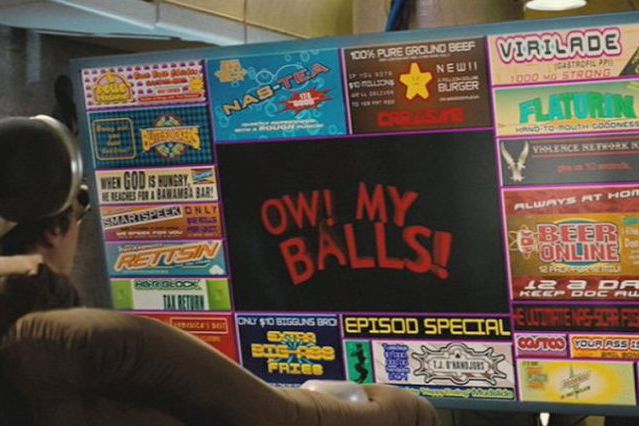

Idiocracy gets a lot right about the future, but by now, it seems more likely that all those space-grubbing pop-ups would be replaced by smooth, subliminal sponsored advertising and product placement. Why watch Ow! My Balls!, when you can watch Carl’s Jr.’s Ow! My Balls! Brought to You By Costco?

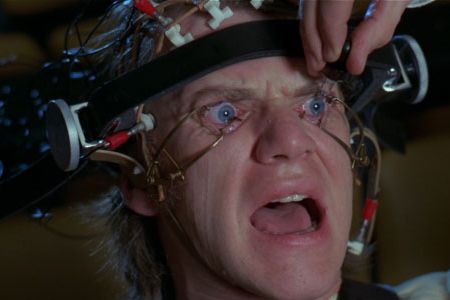

This is not so much a critique of the screen technology on display in A Clockwork Orange as the method of viewing, which does not seem ideal.