From TV to books to movies, dystopian tales are in the air right now. All week long, Vulture is exploring how they’ve been imagined in popular culture.

With the relish of provincial Victorian preachers, sci-fi filmmakers from Fritz Lang to Ridley Scott to Christopher Nolan have prophesied cities that are degraded, damaged, soul-crushing, and ungovernable in startlingly recognizable ways. They are reduced to rubble (like Berlin, Beirut, Grozny, and Aleppo) or else rear eerily out of flatlands (like Dubai), their outsize skyscrapers interlaced with floating highways. They dwarf the scrabbling hordes who have the misfortune to live there, and provide havens to psychopaths with pale eyes and terrible haircuts. Ads flicker and shout from every surface, crowds march through tunnels, and some essential piece of machinery is always about to fall apart or blow up. Their worlds are less different from ours than they might first appear to be. As I watch these movies’ heroes stagger from one underground horror to another, I keep wanting to yell at the screen: “Okay, sure, but have you taken the F train lately?”

Most of us can imagine only what we already know, and even the fantasies of visionary filmmakers can be astonishingly earthbound. The inventors of nonexistent cities don’t have to worry about building codes, zoning, financing regulations, or even the need to make their structures stand up. Rather than use that freedom to unleash radical design or dream up darkly beautiful architecture, they simply recycle the present and make it bigger, and worse.

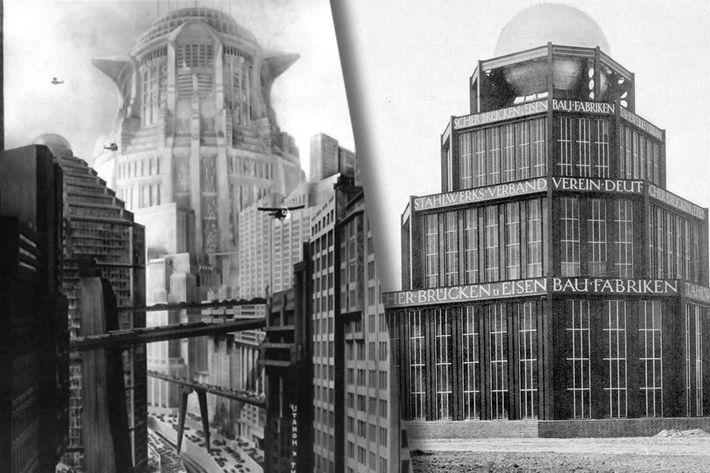

The story of urban dystopias in film generally opens with Lang’s Metropolis, from 1927, a mythological mash-up of Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (with its callow, father-defying hero and subterranean workforce), Frankenstein (a bionic creature pursued by a mob), Genesis (the Tower of Babel tale), and Joan of Arc’s life (a female firebrand who leads the people and is burned at the stake). These intertwined tales take place in a vertically segregated city, in which the wealthy live in high-rise towers and workers toil below. Private cars travel on one set of elevated roadways, workers march along another, and a train glides along a third. Planes weave among towers and fly under viaducts.

“Metropolis was born from my first sight of the New York skyscrapers in October 1924,” Lang said many years later. “The buildings seemed to be a vertical veil, very light and scintillating, a luxurious backdrop suspended from the gray sky to dazzle, distract and hypnotize.” The New York he saw on that visit was not the ethereal arrangement of cascading Art Deco towers that would emerge in the next few years. Instead, it was a city of thick-cut masses: Raymond Hood’s broodingly Gothic American Radiator Building (1924); the Crown Building (1921) in midtown, stepping up like a stacked luggage set; the piled palazzi of the Standard Oil Building at 26 Broadway (1924); and the Equitable Building (1915), which rose so unbrokenly and loomed so oppressively that protests against it led to New York’s first zoning code. Lang was also looking at New York through German eyes. A hexagonal glass tower stands out from the the film’s dense, high-rise cityscape, an apparent merger of Bruno Taut’s 1913 Steel Pavilion in Leipzig and his Glass Pavilion, designed for the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne. Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer’s 1922 submission to the Tribune Tower Competition also makes a disguised cameo, with its blocks of multiple heights, relentless grid of windows, and protruding horizontal slabs.

At the pinnacle of the factory town’s corporate headquarters, a lone plutocrat in a penthouse office looks out over his domain. His aerie, like almost every other interior, is huge and inhumanly bare, the humans made puny by an immense scimitar-shaped desk and double-height doors. Far, far below, workers file through vaulted tunnels and into elevators that shuttle them from underground living quarters to factory floor and back. (Both the Berlin and New York, subways were newish and still growing in the 1920s.) The metropolis they inhabit is like the gargantuan gizmo that rules their lives, a vast machine that demands constant tending and a horde of laborers, but seems to produce nothing but its own existence. The system is rigid and therefore brittle: Like a nuclear reactor, it has a core, and in that vulnerable, pulsating center, even a moment of inattention can have cataclysmic consequences. Beneath this city of terrible order is one of caves and passions, an incubator of revolution.

Lang’s fantasy set the terms for decades of fear. Future cities in later films are almost invariably over-regimented or anarchic, and often both at once. Modernity is a battlefield, where mindless efficiency battles against mindless rage.

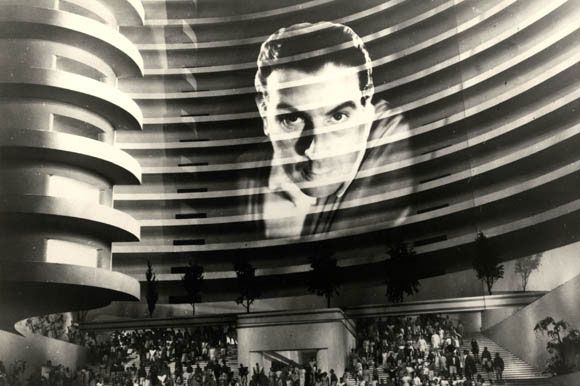

In William Cameron Menzies’s 1936 screen version of the H.G. Wells novel Things to Come, that conflict stretches out over decades. After years of war and technological attrition, the zombielike citizens of Everytown are plagued by the “wandering disease” and go stumbling off into the rubble, only to get picked off by snipers. An eminently reasonable technocrat (Raymond Massey) eventually brings lasting peace, and the city is rebuilt as a subterranean refuge: a climate-controlled world of high-gloss white walls and Lucite furniture. The film is tedious and often silly, but its walls and swooping horizontal bands do offer a distillation of Bauhaus drama and 1930s futurism — styles that were both contemporaneous and forward-looking. The combination of industrial sleekness and imperial grandeur, inhabited by technocrats in stiff-shouldered togas, has a distinctly Fascist look. UNESCO has just added to its list of World Heritage sites the Eritrean city of Asmara, built by Italian occupiers, which includes the 1938 Fiat Tagliero service station, and might practically be a chip off the set of Everytown in 2036.

Since the advanced styles of the 1930s later evolved into movements as different as brutalism, corporate modernism, and the swooping forms of architects like Zaha Hadid, the movie also offers a glimpse into various actual futures. Menzies, like Lang, lavishes long minutes on industrial work, only here it has a clear purpose: reconstruction. Giant white machines stamp out immense panels that cranes lift into place and workers clip to the façade of an indoor building. The scene reads like a vision of the Khrushchyovka, the prefabricated housing that ringed Soviet cities in the 1960s. And with its swooping balconies and see-through elevators, facing onto a soaring atrium, Everytown also resembles John Portman hotels like the 1982 Marriott Marquis in Atlanta.

These movies, like so many later ones, are haunted by size. The 20th century did not invent big buildings, but it did make them common. Even as architects and engineers thrilled to the technical possibilities of megastructures, filmmakers homed in on the contrast between their inhuman scale and the personal dramas playing out in their shadows. In real time, we are approaching 2019, when the Los Angeles of Ridley Scott’s 1982 Blade Runner has been rebuilt as a high-rise megalopolis. (We are also approaching the October release of the film’s sequel: Blade Runner 2049, directed by Denis Villeneuve.) It’s a city at once profoundly disorienting — it’s always raining in L.A.! — and oddly familiar. The Tyrell Corporation occupies a mountainous pyramid that resembles a mutant Mayan temple; cops pilot flying cruisers among twinkling skyscrapers; stadium-size airships hover above the streets, blaring ads for an off-world colony … and the sidewalks are still touchingly equipped with phone booths. Much of the action takes place in the Bradbury Building, which is played by itself; in 1982, as in the movie’s 2019, many of the Art Deco lovelies of downtown L.A. were neglected, largely uninhabited shells.

We often see the city from above, either in panoramic shots of flying craft and building spires, or medium-close views from a ledge onto a street that is alternately dimly lit and lurid. The film’s climactic chase scene involves no vehicles at all, just a man and a woman sprinting through crowded streets, which are flanked by antique 20th-century buildings and packed with noodle stands, columns, lampposts, and assorted urban junk. At ground level, the L.A. of tomorrow resembles the Bangkok of today. Except for the rampages and the perpetual monsoons, this nightmare city has a pleasantly lively, walkable downtown.

What Metropolis implied about the primal forces and raw violence taking over the dystopic city of the future, Blade Runner made explicit, and many movies since then have relied on its tropes. In Dark City, Alex Proyas’s 1998 thriller about manipulated memories, bald, vampiric aliens in long coats and fedoras have warehoused humanity in a dimly lit megalopolis. It’s an unnamed 1940s noir town full of towers that grow on command, rickety scaffolding, and lugubriously shadowed streets. The architecture, as in Blade Runner, is less visionary than creepily nostalgic. There’s even a Hopperesque nighttime view through the window of a barber shop, an improvisation on the painting Nighthawks, with the red lettering on the storefront glass substituting for the woman’s red dress.

Here, too, the basic structure introduced by Metropolis repeats: The vertical city rests on a subterranean one. The fantasy of an army of uniformed mole-people rising up from below keeps recurring, decade after decade. In Metropolis, it was the proletariat; in Dark City, it’s memory-stealing extraterrestrials. In The Dark Knight Rises, Christopher Nolan’s 2012 tour de force of Batman gloom, the basement-dwellers turn out to be a phalanx of good cops. Virtually the entire Gotham police force descends into a subway tunnel to hunt for Bane’s lair, and gets trapped by rubble. Eventually, the rescued officers emerge, grim-faced, shoulder to shoulder, and dressed in soot-stained blue.

The Dark Knight Rises takes place in a future so immediate and a world so familiar that One World Trade Center is still visibly under construction on the Gotham City skyline. Still, it has all the elements of a dystopia sneaking up on a citizenry made complacent by low crime and deceptive prosperity. Batman comes out of retirement when a populist gang of thugs roll into town in street-hogging armored cars, vowing to clear out corrupt politicians and return power where it belongs. The real-world echoes are uncanny, all the more so because they take place in a barely imaginary fusion of New York and Pittsburgh. The Steelers’ Heinz Field played the role of the Gotham City Rogues’ home, but as ground zero of Bane’s terrorist takeover, it also has echoes of the never-built stadium on New York’s West Side that Mayor Bloomberg had hoped would host the 2012 Olympics.

Many of these conventions — prisonlike cities walled off from the surrounding regions, interior voids, oppressively modernist architecture that is at once immense and claustrophobic — converge in Dredd, Pete Travis’s extra-gory, CGI-happy gloss on the Judge Dredd comic books, also from 2012. Eight hundred million people pack into the megacity, which stretches from Boston to Washington, D.C., sealed off from the apocalyptic desert by high concrete walls. The story takes place in one high-rise corner of this vast horizontal expanse: the fictional Peach Trees tower, a 200-story brutalist housing project with armored blast doors.

The filmmakers were looking back, rather than forward. Portman’s Atlanta Marriott from the 1980s is located at, yes, the Peachtree Center, and its immense atrium surely inspired the movie’s Peach Trees tower’s interior shaft, perfect for dropping enemies into.

Elsewhere in Dredd, the Torre de David, a never-completed Caracas bank building that is famously occupied by squatters, supplied the images of families who have converted raw-concrete terraces into barely habitable apartments. The Ponte City apartments in Johannesburg and hulking public-housing projects like Tracey Towers in the Bronx may also have a place in the Peach Trees tower’s genealogy. Dredd’s world dramatizes an old and toxic stereotype of public housing as a set of derelict high-rises where drug dealers control their fiefdoms with firepower. The movie offers a blunt solution, workable only in an alternate reality: an invincible death squad, empowered to wipe out anyone who causes trouble — and to make lethal use of that Portmanesque atrium.

At a time when Manhattan’s towers seem to be growing of their own accord and its underground layers are turning Dantesque, when a ground cover of shanties crowd new luxury towers in Mumbai, and when real-life social-housing towers turn into horrific, nonfictional pyres, movie dystopias cut close to home. Their themes permeate fearmongering documentary videos, like the spittle-flecked gem from Infowars, Why Modern Architecture Sucks, which expresses its distaste for nearly a century of global design — with its dozens of movements, its geniuses and hacks — in candidly political terms: “It’s about using oppressive brutalism to exert authoritarian control over the population.” The NRA, too, recently turned its sights on new urban architecture in an ad that checked off Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall in Los Angeles, Anish Kapoor’s shiny kidney in Chicago’s Millennium Park, and Renzo Piano’s New York Times tower as symbols of liberal excess that has led directly to rioting in the streets. But leave it to the military to distill a panoply of worst-case and worse-than-that scenarios into an adrenaline-filled thriller. A 2016 Pentagon video, Megacities: Urban Future, the Emerging Complexity, shows an urban world ravaged by natural disaster, garbage fires, surging populations, poverty, unsupervised youth, gangs, unstable governments, inequality, religious and ethnic conflicts, stagnation, development, and climate change. “This is the world of our future,” the Dredd-like voice-over intones. “It is one we are not prepared to effectively operate within. And it is unavoidable.” Top that, Hollywood.