All week long, Vulture is exploring how dystopias have been imagined in popular culture.

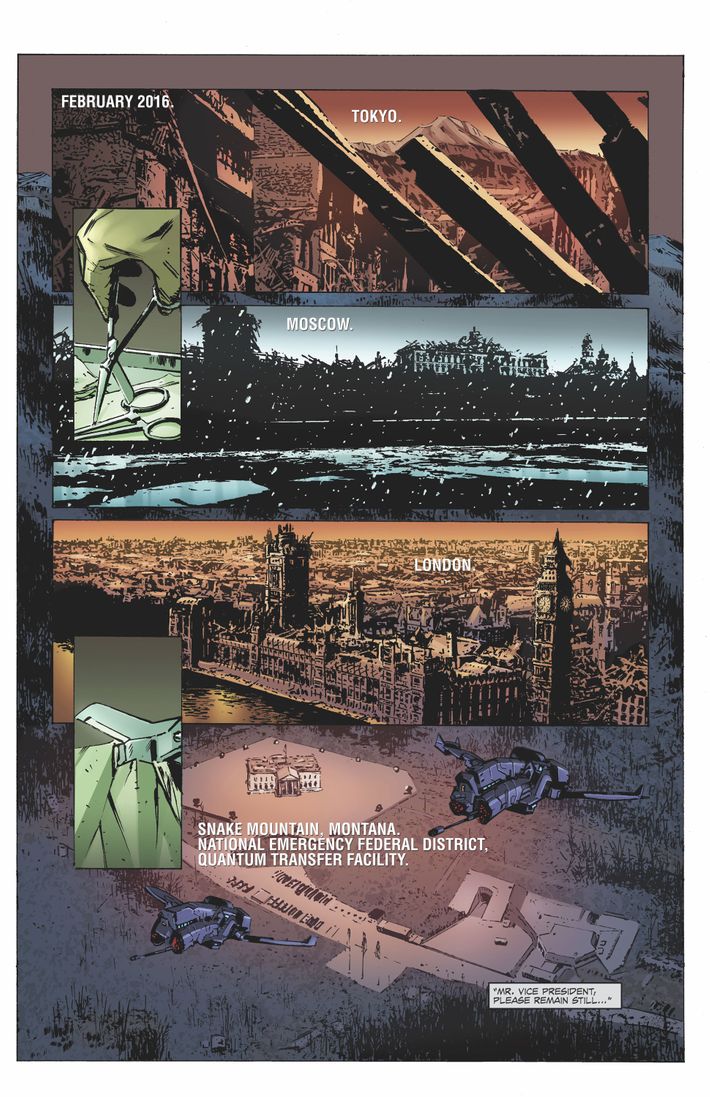

Few authors have crafted more vividly realized future worlds than William Gibson. In timeless classics such as Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive, he dreamed up environments filled with fantastical technology and innovative social arrangements. Those works are often held as seminal works of modern dystopian literature, but in his latest outing, Gibson explores the past, too. Along with co-author Michael St. John Smith and an array of artists, Gibson has created Archangel, a comic book published by IDW that follows a group of time travelers sent from an apocalyptic 2016 back to the smoking ruin of 1945 Berlin. Their mission is to avert world-ending catastrophe, though the contours of that catastrophe remain a mystery for much of the work. As part of VultureÔÇÖs Dark Futures week, we caught up with Gibson to talk about Archangel, but also about dystopian and apocalyptic literature in general.

How do you account for the recent surge in popular fiction about the collapse of civilization into dystopia or Armageddon?

This could be a case of consumers of a particular kind of pop culture trying to tell us something, alas. Seriously, what I find far more ominous is how seldom, today, we see the phrase ÔÇ£the 22nd century.ÔÇØ Almost never. Compare this with the frequency with which the 21st century was evoked in popular culture during, say, the 1920s.

Do you mean itÔÇÖs ominous because people are so pessimistic that they canÔÇÖt even imagine a future?

´╗┐Well, thatÔÇÖs the question ÔÇö why donÔÇÖt we? I donÔÇÖt know.

Why do you think we, as a culture, are so endlessly obsessed with stories about last-ditch attempts to stave off the end of the world?

The end of the world is universal shorthand for whatever we donÔÇÖt want to happen. We have very little control over anything much at all, individually, so fantasies of staving off the end of the world are fairly benign fantasies of increased agency.

What grim future do you fear most? A brutal dystopia? A nuked-out wasteland? A chaotic world war?

I donÔÇÖt think of those as very distinct states. ItÔÇÖs certainly possible to have all three at once.

What research did you and Michael St. John Smith do to craft the story of Archangel?

I think Mike wound up doing more research than I did, mostly about the situation in occupied Germany at the time of our story.

What was the first element of Archangel that came to you? A character? A story beat? A narrative conceit? An image?

Mike knew a German producer in Canada who had heard of a television producer in Germany who was thinking of doing a WWII mini-series there. We pitched the idea of a ÔÇ£Nazi flying saucersÔÇØ story, which was met with brusque disdain, but by then, I was telling Mike what I remembered of the tacky popular mythology of Luftwaffe superweapons. Which eventually became the screenplay for a feature film, and then our graphic novel.

To what extent do you see World War II as a real-life apocalypse? We think of it as a victory, but nothing in human history can match its devastation, after all. Are we therefore living in a post-apocalypse?

I suppose thatÔÇÖs a matter of perspective. In many and various ways, WWII was the change-driver for much of the world we live in. But traditionally, in our culture, apocalypse has been imagined as a single, unitary, short-term event. In that sense, I donÔÇÖt think something that also results in 70-some years of unprecedented socioeconomic well-being for millions of people can count as an apocalypse, even though it was also, at the same time, quite apocalyptic for many of the less fortunate.

There are those who say dystopian and apocalyptic fiction are masturbatory; that they placate us with catharsis when we need to be agitated into action to prevent the real-life collapse of civilization. To what extent do you agree with that outlook?

Much of the planetÔÇÖs human population, today, lives in conditions that many inhabitants of North America would regard as dystopian. Quite a few citizens of the United States live under conditions that many people would regard as dystopian. Dystopia is not very evenly distributed. Fantasy is fun, but naturalism is the necessary balance ÔÇö realism, to be less precise. Naturalistic fiction written today is necessarily fairly pessimistic ÔÇö otherwise, it wouldnÔÇÖt be a realistic depiction of the present. If you were, say, a tiger, and you knew whatÔÇÖs about to happen to your species (extinction, almost certainly), wouldnÔÇÖt it be realistic to have a pessimistic view of things? I think itÔÇÖs realistic, as a human, to have a pessimistic view of a world minus tigers.

What are some of your favorite works of apocalyptic and/or dystopian fiction?

Pavane and The Chalk Giants, both by the British [science-fiction] writer Keith Roberts, both post-nuclear; and The Alteration by Kingsley Amis, a Catholic world in which the Reformation didnÔÇÖt happen.

Do you see any of your work as dystopian? ItÔÇÖs so hard to conclusively define that word.

I think I aspire to naturalism, which today is easily mistaken for the dystopian. When Neuromancer was published in 1984, it was seen by many as a very dark view of the future indeed; yet I knew that the world was full of millions of people whoÔÇÖd migrate to the Sprawl in a flash, if only they had the chance, and be socioeconomically much better off for it.

We live in an age of alt-right trolling, cyberwarfare, corporations mining all our personal data without our knowledge, and smartphone addiction. Has the internet become a dystopia?

Utopia is an absolute, technically. Dystopia seems much more relative a term. There are some scary, unpleasant aspects to the internet today, but then I certainly never assumed it would be utopian.

What are we to make of the last page of Archangel? Is our world just as bad as the one where the Russians get bombed?

That final panel is intended to make the reader wonder, but we framed it that way in order to not be didactic. Better to end with a question mark than with an exclamation point.

How do you maintain hope in these dark times?

One day at a time, and treasuring  those who retain an active sense of humor.