“Lately, I’ve just been like, There’s gotta be a better place than this,” says Mike White. We are in the back room of the Hollywood bar Molly Malone’s, comparing standstill-traffic horror stories like true Angelenos. White, who grew up in nearby Pasadena and has lived in Los Angeles for most of his 47 years, is ready for a change. “I’m so sick of the traffic, and I also find that I’m so culturally lazy here,” he says. “If I go to a different city, I’ll be like, ‘Oh, we’ve got to check out all these places!’ Here, I’m like, ‘Are you kidding? I’ll never drive past the 405 [freeway] right now.’”

If dissatisfaction is an itch, White loves to scratch it. In many of the projects he writes, the lead characters are searching for some way out of a stalled life: The unhappily married Jennifer Aniston mulls an affair with Jake Gyllenhaal in The Good Girl, while in Chuck and Buck, White himself plays a man who can’t move forward until he finds closure with the childhood friend he sexually experimented with. Even when his protagonists manage a breakthrough, they face a world unmoved by their newfound zealotry. In the HBO series Enlightened and in White’s feature directorial debut Year of the Dog, his heroines (Laura Dern and Molly Shannon, respectively) are so determined to heal the world that they make the people around them uncomfortable, while the spiritual masseuse (Salma Hayek) who confronts a morally bankrupt industrialist (John Lithgow) in the White-penned Beatriz at Dinner can barely dent him.

Brad (Ben Stiller), the lead of White’s new film Brad’s Status, is similarly restless, though he can’t see a way out of his predicament. As a top executive at a nonprofit, he is ostensibly committed to making the world a better place, but much of his time is spent hitting up more successful people for donations. Unhappy with a life spent supplicating before those in power, Brad envies the college friends who he feels have surpassed him, including Jason (Luke Wilson), a high-flying businessman, Craig (Michael Sheen), a frequent talking head on cable news, and Billy (Jemaine Clement), who sold his company at a young age and now lives with two beautiful women in a Hawaii mansion. As Brad shepherds his teenage son through the college-admission process, the boy becomes an avatar for Brad’s thwarted ambitions and an excuse for him to dredge up old grudges.

These aren’t world-ending stakes, but in White’s projects, they’re all-consuming. Even his kindest characters have blinkers on, and White is unafraid to dig into his protagonists’ most difficult qualities, all of which are more relatable than we may like to let on. “I look for the things that I’m most uncomfortable talking about,” says White, “and I feel the need to unpack them.” Over the course of an hour at Molly Malone’s, White would do just that.

You pop up briefly in Brad’s Status as one of the college classmates that Brad is jealous of, a man whose mansion is profiled on the cover of Architectural Digest and who throws giant gay pool parties. A lot of Hollywood figures like to signpost their wealth with those pool parties. Ever gone?

I don’t think I’ve ever been to one, to be honest, other than one that we hosted in the movie … which was actually hilarious because we shot that in Honolulu. All of the extras were either go-go dancers or straight surfer guys, and the awkwardness between these guys was just too comical: You could just tell right away who was really uncomfortable dancing on the side of the pool.

You’ve acted in many of your projects, but this one is more like a wordless cameo. Did you write that role with yourself in mind to play it?

No, and honestly, we kind of backed into it. It was a nonspeaking part but we needed someone who could shoot in both Montreal and Honolulu and were we really going to fly some extra around? I thought maybe that if I played him, that could be one thing we just check off the list. The guy who actually plays my husband is actually the DP of the movie, Javier. It was funny because he’s gay and when we were casting in Honolulu, he was like, “You gotta get bears. Aren’t there any bears in Hawaii?’”

What was it like to be the center of all these go-go boys and surfers?

It was an amusing afternoon. Normally, I end up playing the computer geek with a heart of gold or the weird awkward guy, so I just thought it was funny from a meta point of view to be the guy who’s rolling in hedonism and wealth and being the object of envy, as opposed to being the one who’s envying.

Let’s talk more about envy, since it’s one of the big themes of Brad’s Status. You grew up in Pasadena and though you weren’t rich, you were around those who were. How did that inform your sense of the world?

Well, I did grow up with a dad [Reverend Mel White] where it was against his Christian ethos to have a nice house. Any kind of materialism was seen from his missionary parents’ perspective like, “It’s harder for a rich person to get to heaven than the camel that passed through the eye of a needle” Bible-doctrine stuff. I went to a private school where a lot of the kids were really wealthy, and this came out more in Beatriz at Dinner, but some of the conversations and the world of conspicuous consumption was something that I was clocking. Not in a way that I felt like I wanted what they had, but I did notice that was what everyone seemed to want. A part of the legacy of that childhood is that there were times when they would have a cotillion or something, and I realized we were not invited because we were not rich. I guess I’m still clocking it.

Do you have to clock it in yourself as you become more successful? Are there signposts of success you fixate on in ways that you weren’t expecting?

Yeah. I’m a competitive person and my competitiveness has outlasted its usefulness. I don’t go, “I wish I had a yacht,” or something like that but especially in the world of Hollywood, there’s always some new thing everybody is excited about, whether it’s the Oscars or something else. When you’re in that headspace, you can get caught up in the game, even if you try to push it out or block it out. You’ll have lunch with somebody and they’re like, “Oh my God, I loved the Alexander Payne movie!” It’s stupid, but I think people would be lying if they said there’s not some cluster of people who they compare themselves to or have some kind of comparative anxiety with.

When you’re writing about the things you don’t like about yourself, is it like an exorcism?

When I sit and talk to you about some of the anxieties of whether I’m successful in this business, it’s nice in this particular instance that I’ve put all of those things into the movie. Especially in this business, you can be afraid to be seen a certain way or to show that you have these petty thoughts or impulses.

Because no one’s ever had a petty thought in Hollywood?

Of course they do. But you also want to project this vibe like, “I’m cool, I’m above it, I’m just a benevolent, effective, humble guy.” I know some of my contemporaries to be incredibly craven and ambitious and monomaniacally obsessed with work and esteem and prizes and then they make these movies about, like, sheepish sad-sack slackers who are in love with some girl. And I know that guy probably spends 5 or 10 percent of his waking hours thinking about his relationship, because he’s spending 90 percent of it thinking about wanting to be impressive, wanting to make movies that are impressive. That’s so universal in this business. You spend so much of your day being triggered by, like, “Am I up? Am I down?”

Did you have any insecurities over where you went to college?

No. My parents went to nonaccredited Bible colleges, so the idea of even going somewhere like Wesleyan was the luck of having a good college counselor. I grew up here in a very conservative country-club school where it was a lot more conformist, and then I went to Wesleyan, which so blew my mind. The people there were so different from where I was from. I was just stoked that I had found my way out.

And then you returned to Los Angeles after school. What was your post-college experience like?

I was lucky that I had a writing partner, a guy who I went to college with who was older than me, whose name is Zak Penn. He’s a screenwriter and had sold this movie Last Action Hero and he came back to school to visit and was like, “You should come to L.A., I can probably help you get a job.” So I was able to get work pretty quickly after graduating, which was unusual.

Although Zak Penn writes very different movies from you.

Yeah, we didn’t have the same sensibility, so we lasted for about two years. But I was fortunate to meet him because he was a very social screenwriter who knew all the up-and-coming executives, so I met a lot of people through him. For someone like me who will go sit in my cave and write, it was good. It does help to have some foot in the social world of Hollywood.

So when do you differentiate between retreating to your cave to write and deciding that you want to direct your own script, as you did with Brad’s Status?

I guess the way I judge it is, “Is it more stressful for me to go and do it myself and try to get people to do what I want them to do, or is it more stressful to just stand on the sidelines and be the backseat driver and be like, “Really, is that how we’re covering this scene?’’ I’m lucky that Miguel Arteta, who directed Beatriz at Dinner, is kind of egoless in the sense that he’s not afraid to let me answer questions from actors. It’s a collaborative process with him and he understands my tone, so with him that works. But with this one, it just felt like I should do it.

Your characters are often asking themselves some variation of the question, “What kind of person am I?” which I would imagine is also at the forefront of your own mind. Hollywood can turn people into assholes.

I do think as you get older, it’s easy to get burnt out and cynical. At the same time, at this point, I’m not going to pivot. I’m here, and I don’t really know how to do much else. [Laughs.] So it’s still a struggle to make sure it’s meaningful. That’s some of the stuff that I’m drawing from in the movie. You question it: Am I full of shit? Am I doing anything valuable to the world?

Do you consider yourself successful?

I feel successful. If you told me when I was younger that I would be able to keep doing this and I’m still in it, I would be stoked. I feel successful because I’m going to have a lot of movies come out this year. Whether I’m proud of everything, I don’t know, but I’m still in it. It wasn’t obvious to me when I started out that I was going to be able to have a career, so with that, I feel successful.

But then when you get into the nitty-gritty of it, you go, “Oh, it would be nice to have an Oscar, or huge box office.” It’s nice to have everything, you want it all, and then you get caught up in these external markers of what success is and start feeling sort of empty or deflated. I resist it but I still can get caught up in that, and I think that’s what Brad’s Status is about. It’s a sucker’s game. I’ve seen it in Hollywood: People who are at the top levels are still chasing something. It’s a drug, and you get the drug and then the drug fades and you need it again. You see a lot of hungry ghosts who have these great careers and tons of money and all of this admiration and then you get close to it and it’s like, “Wow, this person is so much more miserable than you would expect.”

You were one of the credited writers for this summer’s The Emoji Movie. Was there an idea in there you wanted to explore?

No, that preexisted me. I was on it for three weeks, so it was just kind of me trying to help structure the movie for them. But as far as me trying to express something through it … not really.

You started writing for television shows like Dawson’s Creek, and you’ve periodically worked on big studio films where you may not have much control over the finished product. What appeals to you about taking those jobs?

Honestly, when I get something like The Emoji Movie, I’m grateful. I can come in for three weeks and then go direct my own movie, so I try to be as earnest in how I approach it as anything I do. There was a time when I was doing School of Rock where I thought maybe I could shoehorn my own aesthetic into a more commercial package and those movies could get made, and for a while they were getting made. But as the business has changed, I just think it’s really hard to get original things made even if they are, on their face, more crowd-pleasing. The truth is that it’s gotten so stratified that on a movie like Beatriz at Dinner, you have to defer all your money.

Beatriz did quite well at the indie box office.

But I’m never going to see any of that. I will never see a dime, and they want to defer payments! If I lived off those prorated payments, that would be around $10,000 a year, and I just couldn’t live that way. Especially in the indie world, if you approach it like, “I’m not going to make a dime on this and I can’t even think about that,” it’s the best way to do it because you can just focus on how to get it made the right way. You’re fucked unless you go into it like a pro bono job.

After Enlightened was canceled, you shot a pilot for HBO called Mamma Dallas, about a drag queen who becomes a nanny in Texas. Do you know why the network didn’t pick it up?

I was really proud of the show, and it was heartbreaking because I felt like the actors were really good. To be honest, I felt like HBO was … well, I don’t know what they were hoping for. It turned out very “me,” and it was also a pretty gay-themed show. I think they had gotten so much negative press from canceling Enlightened and Looking and then here comes the creator of Enlightened with this gay-themed show. It was maybe slightly niche so it wasn’t going to be a big breakout show, necessarily. They just didn’t want it.

There are gay characters on television, but there are very virtually no gay shows. And I don’t get it. I think gay lives are much more interesting, on the whole, than most other people’s lives, but I never see that represented onscreen.

But that’s the sad thing. There’s maybe not enough straight people who want to watch that show.

Maybe. But then you see something like RuPaul’s Drag Race, which is 100 percent gay and has really begun to break into the mainstream.

Honestly, I think HBO made a mistake. I think if we had done Mamma Dallas, it’s everything that the culture is talking about right now. It was about a conservative Texas world and this subversive character and there were so many things it could get into, but between Enlightened and Mamma Dallas, that’s when you start scratching your little wounds and going, like, [sad voice], “My show didn’t get picked up.”

This is a big year for you professionally, but a shit year politically. How do you create in the age of Trump?

When we went to Sundance and Trump was being inaugurated, it was nice to have Beatriz at Dinner be the thing we were talking about. It was nice that it wasn’t The Emoji Movie coming out that weekend. You can do something that is bringing people back to the world, instead of escaping it.

Was that a fear you had early in your career, that your work might not matter?

There are some times where you feel, “The world is moving in a more progressive direction so I’ll go make a movie about luchadores in Mexico and have fun doing that.” Then there are times when you feel like, “Okay, all hands on deck.” We do have a purpose. Certain parts of the country can talk about liberals living in the bubble of Hollywood, but I grew up in a conservative Christian community and I can tell you that was the bubble. I got out of that bubble. This is called reality.

You wrote Beatriz and Brad’s Status prior to the election. Will the things going on in the new right now inform what you write next?

I feel like those things make me want to write more. It gives me some sense of purpose, but it’s depressing. It feels weirdly familiar, too. The pendulum shifts and you remember people really respond to this kind of tribalism. Whenever a Republican becomes president, you just go, “Oh, right.”

A lot of people think progress is progress. You forget how easily those gains can be rolled back.

In my experience, the world of liberal progressive politics does include everyone. By its nature, it’s making sure everybody is included in this vision of America, and then with Trump or these other conservatives, you realize their vision of society does not include you. It’s not just about what we should spend our surplus or deficit on or how we should deal with our foreign affairs — it’s literally, like, “Do you belong in this country or not?” And that’s when you feel like your whole being is at stake.

Your dad raised you to be skeptical of wealth and to help your fellow man. What do you think about this controversy where Joel Osteen refused to open his megachurch to hurricane victims?

One of the parables of my childhood was that Jesus could come back in any form, so there was this idea of treating others as you would yourself, and to honor each person as they are. It was not this sort of tribal, materialistic version of Christianity that a lot of these places put forward. I find it really runs in the face of what I think Christianity is and what Jesus spoke and taught.

But material success is so easy to measure and aspire to. Spiritual success is a whole other thing.

That’s definitely true.

So when you’re in bed at night and your mind is racing, you can tell yourself, “I have several movies out this year.” But what really calms you down and makes you feel like what you’re doing is worth it?

The truth is, when I go out and talk to you about these kinds of ideas, or I’m talking to people who see the movie and it sparks some kind of personal reflection, that’s when I feel like this is why I wanted to do this. It’s not even about whether people like the movie or not, but the ideas behind it excite me. I’m really just a channeler of the ideas. It’s like being a chef: I make the soup.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

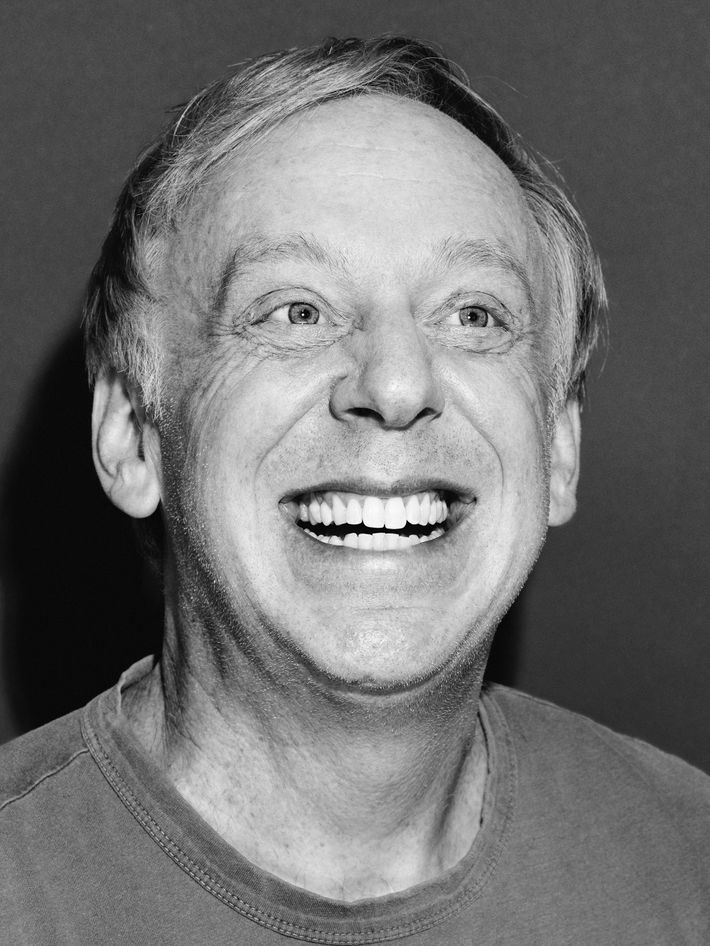

Grooming by Jennifer Brent for Exclusive Artists using Sisley Paris and Bumble and Bumble.