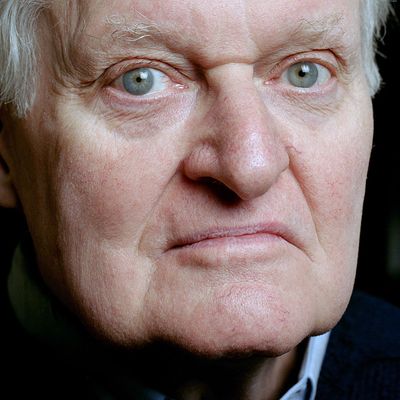

Epochs last a long time, so they don’t end very often and sometimes it can be hard to tell when they do. The death of John Ashbery on Sunday marks a real historical threshold, the passing away of the generation of writers who turned modernism into a tradition.

In American poetry, these writers were grouped together in an anthology published in 1960 and edited by Donald Allen, The New American Poetry 1945–1960. Unless I’ve missed someone, the only writer to outlive Ashbery from that book is Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who is 98 years old. Some of them, like Jack Spicer and Ashbery’s friend Frank O’Hara, died young and now seem to belong to an entirely different time. One obvious quality of Ashbery’s deliberately obscure poetry is his deep interest in language as a living thing in a constant state of evolution, and one of its simplest pleasures is the mingling of registers, formal and colloquial, contemporary and archaic, high art and pop culture. In a lot of Ashbery poems you can feel like you’re being taken on a ride through history, a private history you’d never been aware of before.

Ashbery liked to say that he felt he could communicate more things directly at once if he communicated them obscurely. His style of disjunction and polyphony — beautiful sentences following one after another but appearing to have only a mysterious relationship to each other, if any; the abandonment of a unified voice in favor of many voices without demarcation; the deployment of unstable pronouns without obvious antecedents — put him, inevitably but reluctantly, at the center of debates in American poetry about difficulty and accessibility. It became hard to dismiss him as a charlatan, as many had, after Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror won the National Book Award, the Pulitzer, and the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1976. Instead, he came to represent for some the acceptable outer limit of difficulty, an admirable avant-gardist but a dangerous hero who’d unwittingly led two generations of imitators toward dead ends of self-consciousness and emotional absence. Ashbery figures as a “respectable precedent,” for example, in Tony Hoagland’s attack on the “fear of narrative” and “skittery” poetry that appeared in Poetry in 2006. Up to his death, Ashbery remained the target of parodists, but I can’t remember any parody of Ashbery that didn’t ultimately embarrass the parodist. To effectively parody writing you first have to understand it.

For others — particularly the Language Poets, who cherished his radically fractured second collection The Tennis Court Oath — he was a trailblazer and living proof that the greatest contemporary American poet was one of them. It will be interesting to see if these divisions continue to hold and whether Ashbery’s influence carries on. Will the future be a continued march into new terrain, or a return to the cohesive and confessional?

There are many commonplace things to say about Ashbery’s writing, some of which originated from his own mouth. It’s said that it defies criticism and certainly it defies summary. If you like poems that can be rewritten into a few sentences of prose, his work isn’t for you. Same goes if you like knowing exactly where you are, what time it is, and who’s speaking. Ashbery said that his writing was less hospitable to analysis than it was analogous to an immersive experience like bathing. He wasn’t wrong. You just have to be the sort of person who really enjoys taking a bath in words.

I’m that sort of person, but I never really loved Ashbery’s work until I heard him read it. Something in his pauses and intonation unlocked it for me. He was a true performer, but of the least theatrical, most deadpan sort. It turns out I wasn’t alone. In 1983 Ashbery told the Paris Review: “Often after I have given a poetry reading, people will say, ‘I never really got anything out of your work before, but now that I have heard you read it, I can see something in it.’ I guess something about my voice and my projection of myself meshes with the poems. That is nice, but it is also rather saddening because I can’t sit down with every potential reader and read aloud to him.”

There’ll be no more readings by John Ashbery, but there’s a vast collection of recordings of the poet, collected at PennSound. I’m not sure how many hours the collection currently holds, but it’s possible to listen to Ashbery for the waking hours of a week without repeating a recording. (I’ve done this.) I tend to favor the recordings from the third decade of his career, from his appearance on Bruce Kawin’s WKCR program in 1966 to his recording of “Litany” with Ann Lauterbach in 1980 (it has three parts). “Litany” consists of two separate columns of verse that Ashbery and Lauterbach read simultaneously. Some lines are lost in the dual speaking; others flash out with uncommon power. Listening to it this afternoon I was struck by Ashbery saying:

So death is really an appetite for time

That can see through the haze of blue

Smokerings to the turquoise ceiling.

On the WKCR episode, Kawin asks Ashbery to explain “These Lacustrine Cities” and the result is an invaluable introduction to Ashbery’s method, through the lens of one of his most beautiful poems (one that’s exemplary for the way it toys with its “I,” “we,” and “you”). My favorite of the recordings is an hour-long reading at Harvard’s Sanders Theater from 1976. Here the comic aspect of Ashbery’s work is most obvious, especially in his reading of a poem like “Variations, Calypso and Fugue on a Theme of Ella Wheeler Wilcox,” with its rhyming parody of 19th-century verse. The effect is similar when he comes to the impish last lines of “Worsening Situation”: “My wife / Thinks I’m in Oslo—Oslo, France, that is.”

Ashbery tells the story of the genesis of his poem “Pyrography,” commissioned by the Department of the Interior with a deadline of one day (another poet had been commissioned but not produced a work) for an exhibition of American landscape painting at the Smithsonian. Ashbery at first demurred but then agreed to write the poem when told what the fee was. When he turned it in, officials in Washington felt taxpayer dollars were better spent elsewhere. It’s too bad that happened because the opening lines have a strange patriotic beauty:

Out here on Cottage Grove it matters. The galloping

Wind balks at its shadow. The carriages

Are drawn forward under a sky of fumed oak.

This is America calling:

The mirroring of state to state,

Of voice to voice on the wires,

The force of colloquial greetings like golden

Pollen sinking on the afternoon breeze.

In service stairs the sweet corruption thrives;

The page of dusk turns like a creaking revolving stage in Warren, Ohio.

He grew up on a farm in upstate New York and was, in Harold Bloom’s judgment, the heir to the American Romanticist tradition of Emerson, Whitman, and Stevens. You can hear it too in the last lines of “The One Thing That Can Save America”:

The message was wise, and seemingly

Dictated a long time ago, but its time has still

Not arrived, telling of danger, and the mostly limited

Steps that can be taken against danger

Now and in the future, in cool yards,

In quiet small houses in the country,

Our country, in fenced areas, in cool shady streets.