Mother! is a film brimming with surreal, gonzo cinematic pleasures. Writer-director Darren Aronofsky has created a true feast for the senses that is heavy on mood, texture, sonic landscapes, and visual insanity. He interweaves Gnosticism, Biblical retellings, mythology, and environmental commentary to create a horror film that is as much about the act of creation as it is about the painful, even sadistic ways women are whittled down in marriage by the men who look at them primarily as muses. Whether he’s successful in his aims is another matter entirely. I remain profoundly uneasy about and mixed on the film; I appreciate the audaciousness with which Aronofsky constructs this grand myth, even if I find the cruelty heaped upon Lawrence’s character lacks the emotional nuance necessary to justify it.

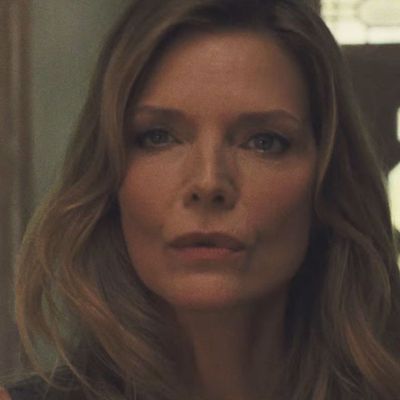

Yet about one thing I’m certain: Whenever Michelle Pfeiffer is onscreen, the film becomes electric. Amid all this chaos, the moment that first leaps into my mind when I think of the film is Pfeiffer, encircling a pallid, frightened Jennifer Lawrence, with a cutting smirk on her face that suggests her character is capable of great violence. She’s the only actor in the film able to give her role real-world weight without sacrificing the mythological nature that undergirds its construction.

The film begins as a tense exploration of a strained marriage through the lens of a young wife (Lawrence) and her much older poet husband (Javier Bardem), whose lives are thrown off balance by a knock at the door — first from Ed Harris, then from his wife, played by Pfeiffer. The film only briefly explores the dynamics of this foursome before it becomes another beast altogether; even after Pfeiffer and Harris’s familial arguments spill blood and madness through Lawrence and Bardem’s home, the focus remains steadfastly on Lawrence. But in brief flashes, Pfeiffer suggests another tantalizing narrative — Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by way of Old Testament fables.

The characters in Mother! aren’t given names, but archetypal titles. Bardem is “Him”; even Lawrence is only credited as “mother.” Pfeiffer and Harris are respectively credited as “Woman” and “Man.” Aronofsky requires his actors to stand in for weighty Biblical and mythological figures — Cain and Abel, Adam and Eve, God — which makes for an overwhelming narrative experience, but also encourages performances that feel a bit weightless, lacking the nuance necessary for their traumas to resonate beyond the realm of allegory. Out of the main actors, it’s Pfeiffer who is able to root the character in meaning — she bracingly marries the exploration of Biblical creation, mythological overtones, and hellish domestic commentary. There’s a gravity to Pfeiffer’s performance that allows her to succeed where the other main actors fail, save for brief spurts — she straddles the boundaries between embodying a symbol and granting the character enough interiority to feel like a flesh and blood woman, too. Pfeiffer’s presence darkens the home, and calls to mind a number of figures: When her hand snakes around Bardem’s shoulder, she feels both like a snake invading paradise and a woman reaching out to hold onto someone in the aftermath of loss. When she cocks her head to the side, examining Lawrence for the right point of impact before slyly going for the jugular with a remark about the age difference in her marriage, I thought of Lilith, and the kind of woman who drunkenly delights in highlighting deep fissures in the lives of others while hers is falling apart. She also suggests Hecate, and most pronouncedly, Eve; she’s the primal representation of woman as sin incarnate, woman as usurper, and also the kind of woman it’s easy to imagine catching in a restaurant window, drunk at brunch. Watching Pfeiffer is witnessing a master at work.

Pfeiffer’s greatness as an actress rests among several contradictions. Yes, she’s able to capably slip between being an icy temptress (Scarface), a reluctant mob enforcer’s wife who pops gum almost as much as she spits out one-liners (Married to the Mob), a latex-clad thief who embodies female fury (Batman Returns), and a harried witch trying to attain eternal youth (Stardust). But Pfeiffer’s recent return to high-caliber films worthy of her talents isn’t just welcome because of her versatility, or her stunning capability to transform physically and vocally for a role. No modern actress better evokes the rich tension between understanding the currency that comes with being a great beauty and the distaste with being seen at all. Pfeiffer’s hostility toward the male gaze in Mother! proves so subversive, it becomes a demonstration of how a great actress can be just as much an author of a film as its director.

In a recent conversation with Darren Aronofsky for Interview magazine, Pfeiffer says of her career, “I didn’t have any formal training. I didn’t come from Juilliard. I was just getting by and learning in front of the world. So I’ve always had this feeling that one day they’re going to find out that I’m really a fraud, that I really don’t know what I’m doing.” The most instructive moment from the interview comes a bit later, when Pfeiffer admits, “I still work pretty instinctually — it’s a little bit like hearing the rhythm of the character in your head.” This instinct and drive to prove herself may be responsible for just how wide-ranging Pfeiffer’s career has been since Scarface: She’s popped up in dark fantasies, overheated noirs, romantic comedies, and big-budget dramas. She’s played yearning single mothers and villainesses, witches and working-class dames just trying to get by. What Pfeiffer proves to be best at is playing women on the edge — of sanity, society, or self-discovery.

Despite only being in the first half of Mother! , Pfeiffer’s energy and prowess are on full display, her impact felt long after she is no longer onscreen. Much of this is due to her physicality, which has always been her greatest gift. Choose any performance in her decades-long career, turn the film on mute, and you can chart the interior life of the woman she plays just by watching her move. In Mother!, it’s a delight witnessing Pfeiffer play a bitch downing spiked lemonade, her body growing languid with each passing sip. Yet she retains the predatory edge and serpentine grace that causes Lawrence to cower.

Of course, if you did turn Mother! on mute, you’d miss how delicious her line readings are, balancing cutting assessments and venomous insults, all wrapped in a drunken haze. Arguably, the scene that best showcases how Pfeiffer uses her voice and physicality is when she travels with Lawrence to the bowels of the house to do laundry. Pfeiffer casually tosses out insults about the unfinished basement and the clear divisions in Lawrence’s marriage. When she closes the space between them to giddily remark on Lawrence’s choice of underwear, Lawrence can’t help but feel smaller in comparison. Pfeiffer is so potent in this role, it’s enough to draw sympathy for Lawrence’s character.

Of course, Lawrence has the trickier role, given how she operates as a stand-in for the Greek mother goddess and embodiment of Earth, Gaia — a more pagan representation of divinity, creation, and the feminine, which is a dramatic contrast to Bardem’s Old Testament–styled God. She’s masochistically dedicated to her genius husband, routinely brutalized, and granted no interior life on the page, save for the occasional sparks of passive-aggressiveness. She’s in nearly every frame of the film, and it’s her perspective that guides us through the hellish wonders Aronofsky creates. Yet as the film continues, she feels less and less like a fully realized person, making it hard for us to feel fully sympathetic, or for her brutalization to come across as much more than a hollow exercise in the grotesque.

This is because Lawrence isn’t quite suited for the role. Lawrence has two primary modes as an actress: stoic, flinty-eyed heroines (Winter’s Bone; the Hunger Games franchise) and broadly depicted showboating that runs entirely on charisma and sucks the oxygen out of the room (nearly everything else, but especially her work with David O. Russell, like Silver Linings Playbook). Here, she has none of that to hold onto. This role requires an actress to have an internal life, projecting more than what is handed to her, as Aronofsky constructs his nameless heroine as Gaia. Actresses like Joan Fontaine and Olivia de Havilland became legends by rendering their unerringly good-natured, masochistically devoted characters with the interiority necessary for you to connect with their plight. Lawrence struggles to do the same, which is increasingly clear when she’s onscreen with Pfeiffer.

Much to the detriment of the film, Pfeiffer is only actor able to consistently suggest her character has a life beyond the walls of the crumbling home that provides the film’s only setting. She grounds her performance and grants it the archness necessary for it to reverberate at the tenor of myth. With a gaze, a smirk, a glare she’s able to suggest an entire history. She delights. She challenges. And like all great actors, ultimately, she transforms.