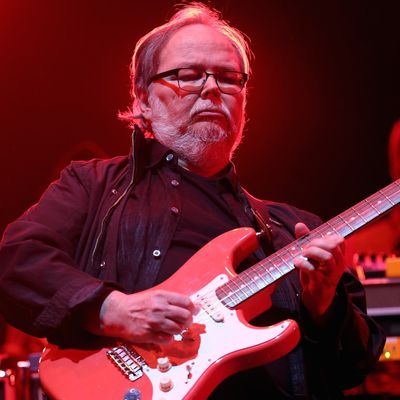

Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, the principals of Steely Dan, had an unusual songwriting relationship. They didn’t split up words and music, and they didn’t write songs individually either. They wrote everything together, and each man’s sensibilities and aesthetics were opaque. The pair entangled their work to the point that they both took each other’s ideas and finished them. “It’s impossible to say who was responsible for the final result,” Becker once said. Fagen is a master keyboardist, Becker a sophisticated bass player. They did great work drawing killer solos out of guitarists like Jeff Baxter, Denny Dias, and Larry Carlton early on, but Becker finally stepped out on guitar himself to get the sounds the pair wanted.

Becker, whose death was announced yesterday, began his career at Bard College. He’d gone, on scholarship, thinking he would find fellow musicians; instead, he found, the college was filled with “rich ne’er-do-wells who couldn’t even be bothered to pick up a guitar,” as he put it later. He was neither of those things; fortunately, he met another actual musician there, someone who’d already wired his way into the scene: Donald Fagen. Soon they were playing together in bands. (One had another student named Chevy Chase playing drums.) In time, Becker and Fagen, forging a friendship and a songwriting partnership, moved to Brooklyn, got a job writing for a minor publisher in the Brill Building, and, after getting a song on a Barbra Streisand album and a stint backing Jay and the Americans, dove into the local music scene and came out the leaders of a group called Steely Dan. (The name came from an industrious dildo in Naked Lunch.)

Fagen and Becker then lived out one of the weirdest success stories in rock. Their vision was an amalgam of jazz and pop, not exactly an established road to riches in 1971. After a few halfhearted tries, they declined to tour — and after trying to run a band, they decided it was too much of a hassle, too. And as for stardom, well, neither Becker nor Fagen could be described as heartthrob material. Yet their albums sold more and more; they crafted a half-dozen Top 40 hits, and closed out their initial career with an epic masterpiece of jazz pop, Aja.

They were actually probably lucky to start when they did; the ’70s have a bad reputation now, but the Top 40 was relatively open, with soul music, hard rock, one-hit wonders, and singer-songwriters vying for dominance in the void left by the breakup of the Beatles. It took a while, but in time the vaguely Latin rhythms and tough guitar solo in “Do It Again,” the first single off the pair’s debut, Can’t Buy a Thrill, caught the ears of listeners and then radio programmers. Steely Dan’s songs were a bit detached, but they were never arch, like Bowie’s; the subjects seem authentic, if disturbed. The band was, unquestionably, one run by, and for, adults, from the keening adulterer in “Dirty Work” to “Change of the Guard,” a song whose title suggested a statement of political defiance neither the lyrics nor the music lived up to.

Pretzel Logic, their third album, is where Becker and Fagen started finding their vision. That album’s first song, built on an amusing cop of a piano line from jazz master Horace Silver’s “Song for My Father,” became their biggest hit. It’s also, many years on, still one of the great singles of its era: “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number.” The pretzel logic of the pair’s lyrics resolve, for three minutes or so, into a simple plea for identity, even existence, all encapsulated in the titular phone number. “Mail it off in a letter to yourself,” sings Fagen unforgettably; it’s probably the first occurrence of the band’s Everyman character, effortlessly voiced by Fagen.

Pretzel Logic, Katy Lied, and The Royal Scam in some way represent the band at its height. Seemingly in control of their career, and rewarded by fans with ever-increasing sales, they took to the studio, summoning top players, and stayed there until their works were complete. Everyman reappears in intermittent moments of clarity and psychic exhaustion, notably in “Any World (That I’m Welcome To)” and the mysterious “Doctor Wu,” who was there when he needed him, or her. Then came what I guess you’d call High Steely Dan: Aja and Gaucho, two pristinely made, unapologetically jazz sonic masterworks. Not a hair out of place, every dissonant harmony (like the ones on “Peg”) discriminatingly, passionately, doggedly created to shine on the superior sound-reproduction system of your choice. And still our Everyman gets older, resigned to mediocrity in “Deacon Blues,” and then, a few years on, haplessly cruising young women in nightclubs in the band’s last top-ten hit, “Hey Nineteen.”

It’s hard to think of another band that floated so effortlessly from New York to L.A. and back again, creating ominous theme music for the lost souls in both places. Never having had the chance to sell out, they pursued their joint vision intently. Touring, they wore the band out and compromised their record-making, so they stopped touring and focused on the records. Their studio perfectionism at the time was legendary — demanding dozens of takes and mercilessly stripping lines by different players from different parts to build the songs they needed. (They even drove Mark Knopfler crazy, ultimately rejecting his solo for “Peg.”) But the result always sounded human, because in the end, a human sound — a sound to match that of their jazz heroes — was what they were after.

Until it didn’t work anymore. “Part of what was going on was that we just liked to be in the recording studio,” Becker said. “We were in charge. Everything good was there. And the circumstances afforded us the rather rare luxury of just going on ad infinitum until we had something that was such an incredible jewel that we would deign to represent it to the public. I thought that was a good thing. But we also developed a perfectionist attitude that came to be more of a problem than a solution.” Indeed, while Gaucho may be the best-sounding record of their classic period, there’s a way in which is fails to have an impact; the sound, an airy pure jazz, becomes almost cerebral.

But by this time, 1980, Becker had what was apparently a heroin problem; a girlfriend died of an overdose. The pair split up, apparently with some acrimony. Becker’s acknowledged that he took the time to clean up and get his life in order. He’d grown up in Queens, with an accountant father; for what it’s worth, Fagen, in his statement about his partner’s death, wrote that Becker had had “a very rough childhood — I’ll spare you the details.”

Becker’s own solo albums strived for the sonic sensibility of Steely Dan’s best work, but his voice can’t carry the things and I can’t recall a great song on them. Twenty years after their split, Becker and Fagen got back together. They’d been part of Irving Azoff’s super stable of artists in the 1970s — that’s why they’d contributed the title song “FM” to the Azoff-produced movie of the same name. They’d always remained loyal to the company, run after the Azoff era by Howard Kaufman. As ’70s nostalgia tours started raking in the big bucks, the pair was finally persuaded to take their act on the road. In fairness, they also noted that they had the control of the venues now to make sure the sound was perfect, and, rather than traveling with a quote-unquote band, they could use their big paychecks to bring along a large group of top players to make the songs come alive. The result, highly enjoyable and the very model of the high-end boomer concert tour, was still an exercise in nostalgia. They recorded two studio albums in the last 20 years, but the songs struggled to have an effect. That didn’t stop the goofs in the Recording Academy from giving Two Against Nature the Album of the Year Grammy in 2001.

Becker’s website announced his death Sunday. Neither it nor Fagen’s statement revealed the cause of death. He was 67. There’s some decent Steely Dan stuff available on YouTube, of course. Here’s the band on Letterman in the latter part of their career; you can see Becker, sporting a burgundy Telecaster, rip up the silky solo on “Josie.”