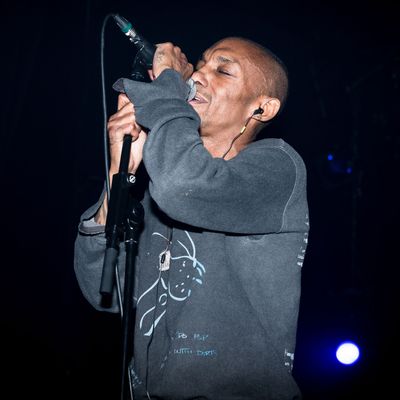

You can’t claim that an artist who dubbed himself Tricky didn’t warn you about being difficult. When he first entered popular consciousness as a rapper on Massive Attack’s debut LP Blue Lines, the Bristol native born as Adrian Thaws made an immediate and indelible impact. Though he only appeared on three songs as a third wheel to core Massive members Daddy G and 3D, his sly and gloomy demeanor swiftly imprinted itself upon listeners’ minds. Though the Massive ethos tended toward self-effacement and group engagement, Tricky nonetheless represented himself as an outlier, a coiled-up loner with plenty of wit and pain to spare; if trip-hop was a counterpart to grunge, then he was its Cobain or Cornell — singular, agonized, and always sourly self-aware enough to keep the whole performance from collapsing into parody. While Portishead named themselves after an environment and Massive Attack after a collective motion, Tricky was unique, twisty and twisted by the fact of being unique. When he declared, on “Five Man Army,” that “people call me Tricky for particular reasons,” the phonetic density almost obscured the wry, prophetic self-assessment. As Tricky’s career would amply demonstrate, being particular is never far removed from being anomalous, weird.

Heavy with downers and rage, the Zeitgeist of the ’90s was more hospitable to the sound of Maxinquaye’s willful intransigence than one might otherwise have expected. The album went gold in the U.K.; the critics spazzed out; David Bowie wrote a prose poem about the artist for Q magazine. Tricky, like the rest of the original Bristol artists soon grouped under the trip-hop rubric, became something of a household name in Britain. An interviewer suggested that he was “nearly God”; so he named his second album Nearly God. Tricky soon realized the pitfalls of celebrity: The same press that showered attention on him was no less eager to pigeonhole him as an unstable young black man. To be fair, he wasn’t entirely stable — trapped in an overstimulated present while still facing a traumatic past, how could he be?

The collections succeeding Maxinquaye labor under a different, less visceral burden: More impersonal questions of fame, society, and divinity (Christology especially), rather than personal misery, lie at their center. What remained constant was a preoccupation with foreignness and alienation, and of course the gloom; no matter which genres it gestured toward (rock, pop, punk, funk, techno, hip-hop), Tricky’s later sound was unremittingly bleak and nocturnal. Burned by fame, he steered himself toward sonics incompatible with mainstream celebration. Whatever genre he flirted with on a given song or album tended to be dragged down, under his influence, by the oblique, interminable ambience typical of dub reggae. It’s best to think of his work as a kind of inverted dub, the permanently relaxed vibes swapped out for the permanently unresolved tensions they had always concealed.

If the intention was to ward off interlopers interested in simple pleasures, the plan went swimmingly. In much the same way that you can’t really go wrong wearing all black, Tricky has yet to make a bad album. But he hasn’t made anything like an accessible album for a long time either. You have to go back to Pre-Millennium Tension (1996) and Angels With Dirty Faces (1998), his last two albums with Martina Topley-Bird as female vocalist, to discover anything remotely welcoming or soothing. The critics, aside from staunch Tricky loyalist (and, not coincidentally, renowned killjoy) Robert Christgau, have moved on as well; after all, once things get too dark for too long, it’s tempting to announce there’s nothing more to see.

Billed by the artist as a return to Maxinquaye’s sound, Ununiform, the 13th Tricky album, released today, marks a departure in the form of a return. After nearly 20 years, Topley-Bird is gracing Tricky’s instrumentals once more: “When We Die” approximates the dreamy, luxuriant urgency of their original collaborations to great effect. Still, it’s only one song, and its placement as the album closer feels more like a last embrace than a renewed relation. Topley-Bird’s the best-known of the grab bag of featured artists typical of Tricky albums since her disappearance. A bevy of other, expensively named women (Francesca Belmonte, Italian actress Asia Argento, Mina Rose, Terra Lopez, Avalon Lurks) plus a pair of Russian-language rappers named Scriptonite and Smoky Mo comprise the rest of the ensemble of collaborators. The sound is likewise much diversified compared to Tricky’s earlier albums, sliding easily from pensive tracks centered on acoustic guitar (“The Only Way,” “Doll,” “Running Wild”) to serrated dance (“Dark Days,” “Armor,” “Same As It Ever Was,” “Bang Boogie”) to songs best described as lurkers (“It’s Your Day,” “Blood of My Blood”) to brooding futurist soul (“Wait for Signal,” “When We Die”). This isn’t really a new feature — Maxinquaye had its fair share of left turns too. As the title implies, Ununiform isn’t meant to be even. If it marks a resumption of Tricky’s oldest tendencies, it’s also a continuation of his more recent forays into dissonance and melody.

It’s a testament to his extreme singularity that, a quarter-century after his first appearance on wax, Tricky still possesses sounds entirely his own. No one has touched him. He remains as impervious to mainstream assimilation as ever; it’s safe to say that if he had never existed, no one would have invented any of his albums. He’s still active, still searching for new angles on darkness, one not entirely his own. Well before intimations of the end times and confusions of gender, race, class, nation, and mental health dominated daily discourse, Tricky had already claimed such topics for himself, exploring and elaborating them with shadowy diligence. When he repeats “Where do we go?” on “When We Die,” it’s a reminder of the unswerving focus on the time to come that’s kept him relevant at a deep level while preserving him from the superficial inflations and deflations of trendiness. He’ll never be a superstar in the world we live in currently, but being a reliable guide on a troubled planet, without losing one’s mind or one’s cool, is a major achievement. Present artists should learn from him; artists of the future will — assuming, that is, that there’s any future at all.