DC Comics (or DC Entertainment, as it’s now known) has published a handful of self-evaluations in the past 30 years, all of them oriented toward the sixth year of a given decade. The process began in 1986 with Crisis on Infinite Earths, a legendarily expansive tale in which the whole DC multiverse was evaluated and destroyed. In 2006, a sequel called Infinite Crisis executed a similar set of revisions. Last year, Rebirth took a look at how dark and alienating the world of DC had become, and restored a sense of what president and chief creative officer Geoff Johns repeatedly referred to as “hope and optimism.” But it would seem that the one year they skipped was 1996, which saw no Crises or shake-ups.

In fact, 1996 brought its own state-of-the-union manifesto. It was a smaller one, only four issues in length. It had no cosmic implications. It wasn’t a crossover. Very little in the mainstream DC status quo was changed by it. Co-written by Mark Waid and Alex Ross and drawn (well, drawn and painted) by Ross, it was titled Kingdom Come, and it was, perhaps, the greatest DC self-assessment of them all. Indeed, it stands as one of the best superhero stories ever told — and one that every comics publisher would do well to revisit and be inspired by today.

Its origins lay in pure love of its cast. Ross had just made his bones two years earlier at DC’s eternal rival, Marvel Comics. There, he and scribe Kurt Busiek had published a love letter to that company’s mythology called Marvels, which attempted to unify decades’ worth of Marvel stories into a single, beautiful narrative. After it stunned readers and the comics establishment, Ross turned away from the past to look forward, drafting a 40-page pitch for a DC story set in the near future. The company was interested and assigned him a co-writer with an encyclopedic knowledge of all things DC, but with only a year or so of experience as a full-time scribe — Mark Waid. Thrown together by fate, they got to work.

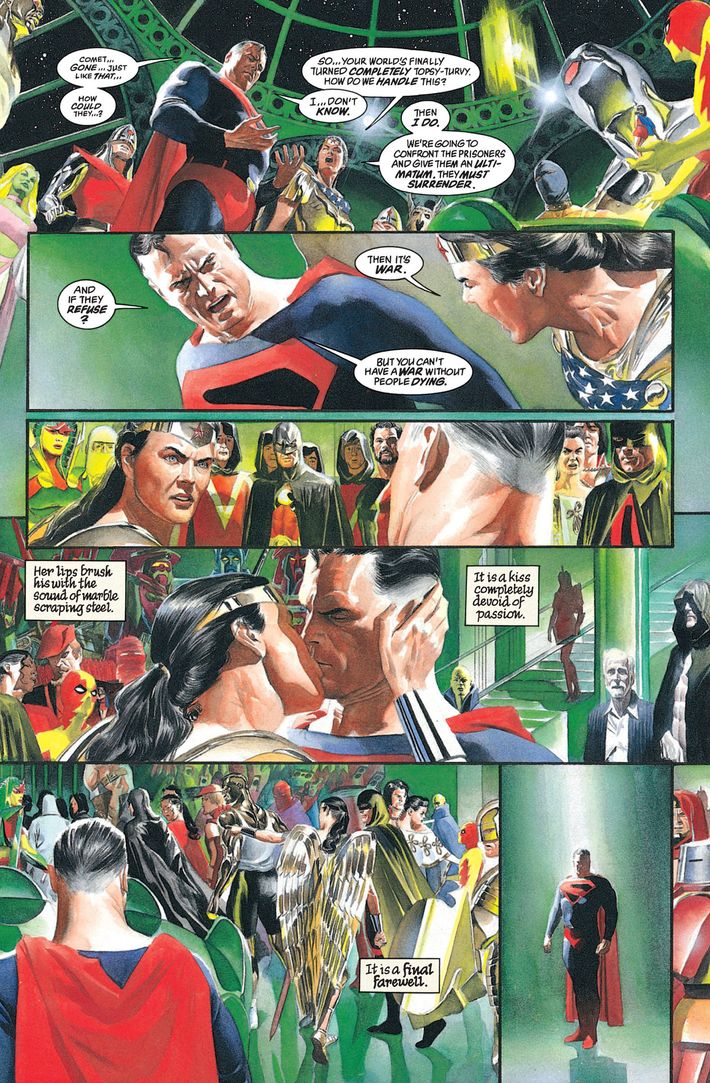

In contrast to the various Crises, Kingdom Come’s plot is blissfully straightforward. A few years ahead of the present, a new generation of superheroes has become violent, irresponsible, and relatively unconcerned with the needs of the humans they’ve ostensibly sworn to protect. These characters were a passionate critique of the then-current state of the superhero genre, where lethal justice were the order of the day and grim anti-heroes were held up as the only tool for telling “mature” stories. Furthering the metaphor, within the story, the classic DC pantheon — Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, the Flash, and their ilk — have faded into the background, or, in the case of Superman, outright gone into retirement. A particularly destructive battle waged by the new superheroes leads to a nuclear disaster and Superman returns alongside his erstwhile partners. The various heroes fall into disagreement over evil-fighting tactics while their rogues’ gallery come out of the woodwork, and a nigh-apocalyptic battle ensues.

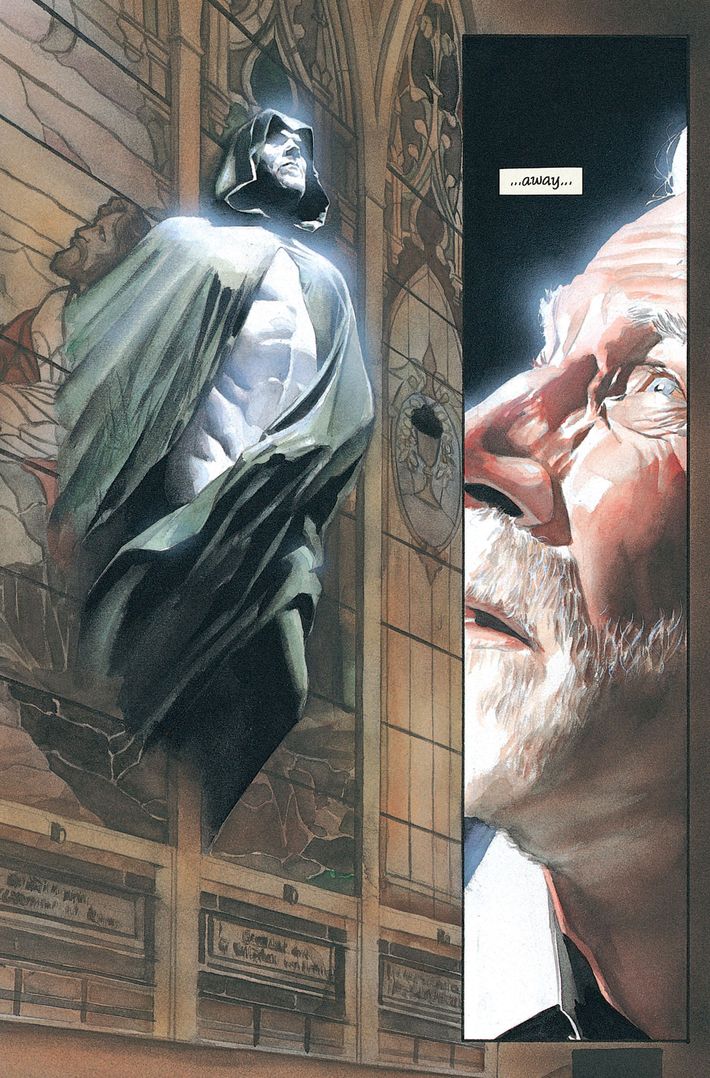

Surprisingly, the beating heart of the story isn’t Superman or any of the other big names of the DC universe — it’s a pronouncedly non-super human named Norman McCay. He’s an aging reverend at a church whose membership is declining in this cynical era, and one day, he’s visited by DC’s resident angel of God, the Spectre. The eerie entity informs a reluctant and terrified Norman that he’s been chosen to watch the events to come and make a judgment about superhero-dom at the end. It’s thrilling to see a reimagined version of the Spectre if you’re a longtime DC fan, but no previous knowledge is required of the reader. You can simply appreciate the notion of an avenging member of the heavenly host descending to recruit an ordinary man for a grand mission.

That’s one of the great virtues of Kingdom Come, and one all too often eschewed in superhero comics: It’s wholly accessible. To be fair, Ross and Waid constructed a story that is filled to the brim with Easter eggs for superfans: a book from the continuity of Watchmen is on sale, Jimmy Olsen’s alter ego Turtle Boy appears on a TV screen, characters are illustrated in Ross’s photorealistic style to resemble comics creators like Brian Azzarello and Jill Thompson, and so on. Yet somehow, against all odds, none of that gets in the way. The main story probably requires some basic existing appreciation of Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman, but what red-blooded American doesn’t possess that? It also helps to know that there’s a guy named Captain Marvel who is powered by magic and whose alter ego was an ordinary boy named Billy Batson. Everything else can be simultaneously appreciated by both diehards and dilettantes.

The same cannot be said of the vast majority of superhero comics, let alone operatic ones that seek to assess all that has gone before. Pick up any individual issue of a modern Marvel or DC series, even ones billed as a great jumping-on point for new readers, and you’re likely to encounter more than a few stumbling blocks. Key plot points will be built on stories both recent and distant. Characters will appear without sufficient introduction. The whole endeavor is likely to feel more than a little alienating for a novice. That doesn’t mean those stories aren’t worthwhile, by any means — the rich brew of continuity is a delicious and addictive aspect of superhero storytelling that one can’t find almost anywhere else. But the balance has long been out of whack: There are way, way more stories that require expertise than there are ones that don’t. Kingdom Come, by contrast, has its cake and eats it, too. It should be required reading for anyone hoping to write a superhero story set within an existing shared universe.

It should also be required reading for publishers who take hard-earned dollars from readers through so-called “decompressed” storytelling. There’s been a tendency in the past decade and a half or so to stretch stories out over far more issues than are necessary to contain the plot. Time was, you’d get an iconic and genre-altering tale like Chris Claremont and John Byrne’s “Days of Future Past” in just two issues of Uncanny X-Men. Flash-forward to today, and a big “event” story like this year’s “Secret Empire” spans ten core-narrative issues and dozens of lead-up and tie-in installments in other series. Part of that is due to the evolution of storytelling in comics — they’re written more like screenplays now, with beats that play out with human-sounding dialogue, rather than pithy exclamations and dense internal monologues. But oftentimes, it’s just laziness and buck-milking.

Not so with Kingdom Come. Each issue comprises roughly 25 percent of the story, all while feeling naturalistic (well, as naturalistic as a story about folks who dress up in tights and punch mental patients can be) and thick with emotion. In chapter one, the dramatis personae are introduced, the scene is set, and the conclusion teases a coming apocalypse. In chapter two, plans are put in motion and sides are chosen. In chapter three, surprises escalate the action and chaos breaks out. In chapter four, the great battle occurs and a climactic decision is made. The short epilogue brings all the questions down to a quiet, personal level, and hope is provided for the future. Ross and Waid execute something of a master class in how to lay out a self-contained superhero opera. It’s as cathartic as it is provocative, and never feels like it needs additional embellishing.

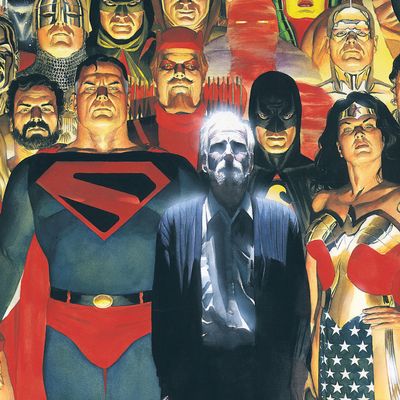

The only place for embellishing is in the artwork. Much has been said and written about Ross’s approach to envisioning caped crusaders and men of steel, and it’s appropriate that much of that analysis came in a book about his work with the heading Mythology. Few visual artists have ever matched Ross’s capacity for grandeur — a curious thing, given that his whole deal is making the characters look real. Shouldn’t reality be a paltry substitute for the uncanny whizzes and bangs of traditional comics art? Yet that paradox is exactly why the eye boggles. You see impossible things happening — flight, power blasts, space stations made of corporeal light — but they look as though they’re happening in your own world. Suddenly, you’re not just a reader; you’re a traveler who has somehow climbed Olympus and seen the gods with your own two eyes. For a story of this scope, no other artist would have been appropriate.

Nor would any other one have been allowed, given that the whole thing was Ross’s idea in the first place. It’s hard to imagine him relinquishing control over Kingdom Come (though it was later stolen from him in a subsequent set of spinoffs called The Kingdom, which we’ll get to in a moment), and he and Waid proved a potent pairing. The overarching narrative is wonderful, but what sticks with you are individual moments, lines, and visuals. They had a knack for doing what superhero comics do at their best, which is present big ideas in ways that pierce through your mental defenses with action and invention.

There’s the end of issue one, where Superman comes back to save the day and towers above a crowd with two vigilantes in his hands and a disappointed-father look on his face, a crowd erupts in cheers, and Norman thinks to himself, “He is returned — and — dear God. The threat of armageddon hasn’t ended. It’s just begun.” There’s the single, scene-beginning panel in which immortal villain Vandal Savage snaps a secretary’s neck while saying, “I said two sugars.” There’s Lex Luthor brainwashing a pitifully horrified Captain Marvel by showing him manufactured images of superhumans destroying the world; Marvel says, “Those … those things never happened,” and Lex invents fake news by replying, “But they could have. And that’s the point, isn’t it?” Speaking of inadvertent commentary on our current national predicament, there’s the bit where a xenophobe named the Americommando attacks a group of immigrants at the Statue of Liberty while declaring war on “the most insidious menace of all! The poor, tired, huddled masses camping on our shores begging citizenship!” And you’ve gotta read the part where we learn how Batman orders a steak.

But as great as these moments are, they would be nothing if the story didn’t stick the landing. I won’t spoil how high the crescendo rises, or what specific note it ends up striking, but suffice it to say that Kingdom Come presents an unusual and utterly thought-provoking thematic conclusion. Superhero fiction is fundamentally about power and its responsible use, and the lesson we and Superman learn is that the powerful can only afford to be paternalistic to a point. It’s all well and good to be a protector, but what does that cost those who are protected? Once you take away the agency of the less powerful, you make yourself something of a colonizer, however benevolent you may be. Democracy is lost. Cooperation is lost. The polity is lost. Power is power and its existence cannot be denied, but those who wield it would do well to understand that it has to be wielded in collaboration with those who lack your abilities, and that you have to listen to what those latter people say. Otherwise, the repressed will always return and a price will be paid.

And yet, appropriately enough, this lesson, itself, isn’t presented in a paternalistic fashion. Waid and Ross don’t talk down to you and say they have all the answers — there’s plenty of room provided to dispute their findings, if you so choose. But the fact remains that their findings are solid, and not regularly explored in other superhero fiction. That doesn’t mean Kingdom Come left no legacy, though. There was that aforementioned spinoff, The Kingdom, which explored the lives of an array of minor characters from Kingdom Come, to varying levels of quality. But Ross was uninvolved, and it felt way too much like just another exploration of an alternate universe, rather than something singular and special. In addition, a few characters underwent makeovers or renamings that were inspired by their depictions in the story. Luckily, you don’t have to read any of that stuff to appreciate Kingdom Come. More than two decades later, that appreciation comes naturally to anyone willing to pick up a text that both celebrates and critiques the genre that has come to conquer entertainment. Its will be done, on Earth as it is in Heaven.