In this, the year hip-hop won the music business, one of its defining hits was released more or less by mistake.

Back in February, Lil Uzi Vert, a charismatic, septum-pierced 23-year-old rapper out of Philadelphia who’d become internet famous with a frenetic outpouring of digital singles, EPs, and mixtapes, was on his first tour of Europe, opening a string of shows for the Weeknd. Uzi, who counts late nihilist punk GG Allin and ’90s shock-rocker Marilyn Manson as heroes, dove into the crowd during a gig in Geneva. Backstage after the set, he realized he’d lost his phone during the plunge. “He lost two phones, actually,” says Leighton “Lake” Morrison, one of the principals, along with veteran producers Don Cannon and DJ Drama, of Uzi’s Atlanta-based label, Generation Now. “And he’d broke the screen on a third.” Prior to Europe, Uzi and his team had been in L.A. and Hawaii, working on tracks for his first official album, to be released on Generation Now through Atlantic Records. The songs they’d finished were on one of the lost phones.

“Yeah, I was upset,” says Morrison. “We’d just spent a month and half recording in Hawaii, and I had to justify all this money Atlantic had given us that we’d just blown.” Uzi had lost a phone in 2016 that contained some new collaborations with fellow mumble-rap fashion plate Young Thug, and those were soon leaked on the internet. “We didn’t want to go through that again.”

In this new digital era of music consumption, brought about by streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music, many hip-hop artists have rejected the traditional blueprint for releasing new music, which mimicked Hollywood’s rollout of a blockbuster film: a lavish, many-months-in-the-making marketing campaign, led by one or two radio-friendly singles designed to create maximum exposure for a record company’s big moneymaker, a proper studio album. Streaming is built on a song-based economy, though, and young MCs like Uzi are too savvy and restless to play by the old rules: They spray-hose new tracks when the mood strikes, and fans binge the content like couch-bound Netflix addicts inhaling new episodes of Black Mirror. “Hip-hop artists have liberated themselves from the shackles of the album,” says Lyor Cohen, co-founder of pioneering rap label Def Jam and now YouTube’s global head of music. “The album is far less important than just putting out music.”

That night in Geneva, Uzi wasn’t thinking about upending the norms of distribution. In the three years since he uploaded his first song onto the DIY streaming platform SoundCloud, he’d collaborated with everyone from Gucci Mane to Pharrell, built a 4-million-plus Instagram following, and racked up a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 record with his featured verse on Migos’s viral smash “Bad and Boujee.” “Streaming has definitely made me money,” says Uzi. “It’s a whole other way to put your music out there.” Back at his hotel, he reached for his laptop and logged onto his SoundCloud account. Minutes later, he texted Morrison in Atlanta. “I just leaked everything I recorded,” he wrote. “There wasn’t even any artwork,” shrugs Lake. Uzi made up song titles on the spot. He called one “Boring Shit.” And another was hurriedly named after the Weeknd tour, carrying not even a hint of the song’s content in its title.

“XO Tour Llif3,” a gothic, Sturm und Drang–filled relationship saga about his then-girlfriend Brittany Byrd (and drugs) that features the sticky, none-more-black refrain “All my friends are dead / Push me to the edge,” became an immediate sensation among the fevered rap nerds on SoundCloud. One month later, after Generation Now had sorted out producer credits, it was added to Spotify and Apple Music. There too, the response was instantaneous and overwhelming. Spotify’s Tuma Basa, the curator of streaming’s most important playlist, RapCaviar, with 7.6 million followers, says approvingly that when he listens to “XO Tour Llif3,” he imagines “Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love arguing. He’s telling a story. Guys like Uzi keep me excited about this shit.”

Still, few could have predicted that Uzi’s warbled soap opera would eventually be voted Song of the Summer at the 2017 VMAs. “I couldn’t have planned it any better if I’d tried,” says Julie Greenwald, co-chairman and COO of Atlantic. “XO Tour Llif3” also made history on the May 6 Billboard Hot 100 as one of five hip-hop songs in the top 10, only the second time that Billboard’s preeminent chart featured five rap songs (Kendrick Lamar’s “Humble” was No. 1; Lamar’s “DNA” No. 4; Future’s “Mask Off” was No. 5; Kyle’s “iSpy” featuring Lil Yachty No. 6; and “XO Your Llif3” No. 10). Strikingly, these songs were getting little to no airplay on the nation’s hit-driven radio stations, traditionally, along with sales, the most powerful factor in determining a song’s Hot 100 placement. “Let’s be honest,” says a top major-label executive: “No cool kid is listening to top 40 radio.” Instead, those kids are glued to streaming services.

Spotify, which launched in the U.S. in 2011, may be the most effective and efficient new platform to promote and monetize recorded music since the advent of MTV in the early 1980s. Adding users by the millions every month, it now claims 60 million subscribers and 140 million overall users. Spotify and Apple Music (which has around 27 million subscribers), along with YouTube, Pandora, Amazon Prime Music, SoundCloud, and the Jay-Z–backed Tidal, have propelled the recorded-music industry, in wreckage since the launch of the file-sharing service Napster in 1999, to double-digit revenue growth for the first time since — you guessed it — 1998. In 2016, revenue generated from streaming services grew 69 percent year over year, to $3.9 billion; for the first time, streaming accounted for more than half of all recorded-music-industry revenue.

And in numbers that sometimes strain belief, users are opening their Spotify or Apple Music apps and streaming hip-hop and R&B tracks at nearly twice the rate as the next most popular genre (rock), according to the research company Nielsen. In fact, Nielsen announced in June that R&B/hip-hop has become the most popular genre in music for the first time since it started compiling such data. Certainly, there are still superstars who sing conventionally crafted pop songs and command armies of fans, as evidenced in the royalty statements for Ed Sheeran, Justin Bieber, Adele, and Taylor Swift, and once every couple of years some Hot Topic angst-rock band like Twenty One Pilots wins the heartland. Not to mention that the real money, for everyone from Father John Misty to the Chainsmokers to Bruce Springsteen, comes from concert receipts, merchandise sales, and brand sponsorships and endorsements.

But in the youth-obsessed music business, relevance is both fetishized and easily measurable, and there are no more streamed, and therefore no more vital, artists in music than the new breed of hip-hop stars — Drake, Kendrick, Migos, 21 Savage, Chance the Rapper, XXXTentacion, Rae Sremmurd, Future, Travis Scott, Cardi B, Lil Uzi Vert — found in the upper reaches of RapCaviar and Apple’s A-List: Hip-Hop playlist. As I write this, seven of the ten most-streamed songs on Spotify come from hip-hop artists (two are from Swift, and one is a collaboration between EDM DJ Marshmello and R&B singer Khalid). This is no anomaly; the “over-indexing” of hip-hop, as marketers call it, has become the norm. Apple Music typically leans even more hip-hop than does Spotify: There, it’s 9 out of the top 10 (Cardi B’s “Bodak Yellow” is No. 1, with Swift’s “Look What You Made Me Do” the outlier at No. 9), and an astonishing 18 of the top 20. There’s no sign of LCD Soundsystem, Arcade Fire, Lana Del Rey, Katy Perry, Lorde, Haim, or even Miley Cyrus, to name just some of the high-profile rock and pop artists with splashy new records on the market.

For a music industry still dominated by a handful of major labels, this profound synergy between hip-hop and streaming has upended business strategies, prompted outrageous bidding wars over new rap talent, devalued both emerging and A-list female pop singers, further hastened the commercial and cultural irrelevance of rock, prompted star EDM DJs like Calvin Harris to feature brand-name rappers on their latest tracks, and even challenged some longheld assumptions about race and music.

“Hip-hop has become, finally, the key youth music,” says Peter Edge, chairman and CEO of RCA Records, which represents hip-hop/R&B star Bryson Tiller, A$AP Rocky, and breakout female alt-R&B singer SZA. “It’s the new rock and roll.”

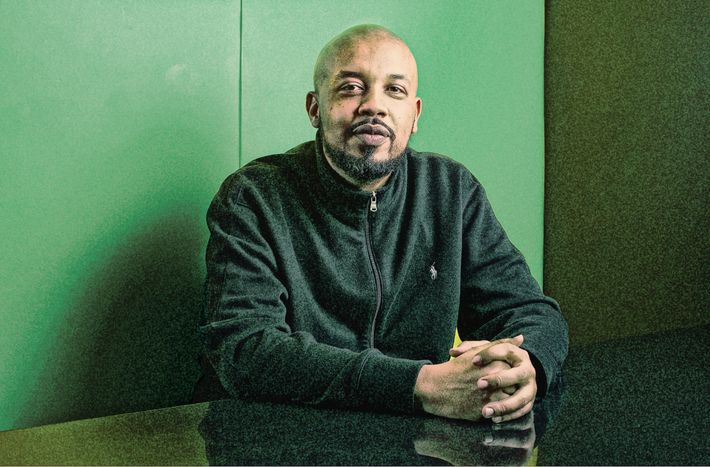

On a comfortable mid-July afternoon in New York’s Flatiron district, Spotify’s Tuma Basa is entertaining VIP guests in one of the company’s conference rooms. Basa is the global programming head of hip-hop at Spotify, which puts him in charge of RapCaviar, a hand-picked, 50-song grouping of, in Basa’s estimation, the very best new hip-hop songs.

“RapCaviar reminds me of Hot 97 in the early ’90s,” says Joie Manda, executive VP at Interscope Geffen A&M Records, referring to the powerful NYC radio station. “When Hot 97 played ‘Protect Ya Neck’ by the Wu-Tang Clan, that was it. It went all over the country. RapCaviar has that influence right now. A song goes in RapCaviar and everyone pays attention. And lucky for us, Tuma’s an expert. He knows what kids want.”

Basa, 42, is about as friendly and self-effacing as a powerful tastemaker can be. Now a resident of Harlem, he was born in former Zaire, but spent his formative years in Iowa City — where his father was earning his Ph.D. in English — and then Zimbabwe. He was a teenage Boyz II Men fan there when he first managed to get his hands on the music that would change his life. “In Zim, you couldn’t always buy the original cassette release of a record,” he says. “So I would go to Swaziland with VHS copies of [seminal video shows] Rap City and Yo! MTV Raps that my friends in Iowa had sent to me, and I’d swap my VHS tapes for music with friends in Swaziland. I’d go back to Zim and be the only one with copies of Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle and Tupac’s 2Pacalypse Now.” The irony of now working at a company whose very premise — not to mention its $13 billion valuation — is built on ubiquitous, instantaneous access to more than 30 million songs does not escape him.

Manda, a Gravesend native who over the years has worked with hip-hop A-listers from Gucci Mane to Frank Ocean, has flown to New York from L.A. to introduce Basa to a new signing, a Memphis rapper with the spectacular name Moneybagg Yo. Moneybagg’s mentor, Memphis legend Yo Gotti, is also here to schmooze Basa. Basa oversees 30 or so playlists, ranging from artist-specific — e.g. This Is: Lil Uzi Vert (49,000 followers) — to not-quite-ready-for-prime-time jams (Most Necessary, 1.3 million) to mood-based (Get Turnt, 2.9 million). “Playlists make it easy to keep up with hip-hop,” he says, “the same way that a newspaper made it easy for your dad to keep up with sports. Because hip-hop moves fast. I do this for a living, and even for me it’s a lot.”

Moneybagg’s songs have already appeared on the regional playlist The Realest Down South (324,000 followers), but the dream is to be featured on RapCaviar — “one word,” reminds Basa, “because of Aristotle’s ‘the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.’” Basa selects the songs for RapCaviar on his own, utilizing predictive skills — “gut, gut, and gut,” he declares — honed at previous programming gigs at BET, MTV, and Revolt TV. “When something comes in and doesn’t smell right, I can detect it. ”

At Spotify, Basa also has access to a trove of data that enables him to gauge a song’s performance across the site: from how many times a song or artist has been searched for, to playlist-specific metrics such as percentage of people who skip the song (under 40 percent is desirable), percentage of saves to a user’s own playlists and percentage of users who listen to more than 90 seconds of a song, known as completion rate. When his instincts falter, Basa crunches the numbers. “Earlier this year,” he says, “one of my former co-workers at MTV called me. He’s business partners with XXXTentacion’s manager,” referring to the controversial underground rapper. “He said, ‘Yo, this guy is blowing up on Spotify.’ I said, ‘He is?’ I looked up his search results, and I’m like, ‘Oh shit. He really is.’” So I put it on Most Necessary, and reaction was instant.”

Part data scientist, part romantic laboring over a cassette mixtape, Basa sees himself as part of a hip-hop tradition. “Hip-hop has always valued curators: DJs, mixshow hosts, radio personalities,” he says. “This is just a different manifestation.” Officially, RapCaviar is updated weekly, whereby five or so new songs get cycled in, but Basa is often fiddling with it. Later in August, on a trip to Atlanta to kick off RapCaviar’s new series of branded concerts, he stops our conversation mid-sentence and grabs his Mac to add a track by rapper Ugly God, “Stop Smoking Black & Milds.” Over the weekend, he says, site search spiked for Ugly God, a leading indicator for Basa of vitality. To make room, he studies the data on a pair of J. Cole songs. One, “Change,” has a fairly high skip rate. With a couple of keystrokes, the song is ethered from the playlist. “If Tuma moves your song down on RapCaviar, your shit’s not working too well,” says Atlantic’s Greenwald.

Back in the conference room, Yo Gotti is reminding his artist of the importance of RapCaviar to today’s hip-hop economy. “Spotify is the new street,” he declares, and pushes play on one of Moneybagg Yo’s new tracks, “Trending” (“I’m trending / My shirt, my belt, my shoes, the shit come from Fendi”). Basa grins and nods along to the beat. When the room quiets, Manda makes his pitch for Moneybagg (“we think he’s gonna take this shit over”), but then shifts the conversation to the bull market for hip-hop, shaking his head in mild disbelief. “The whole world wants rap,” he says. “It’s our time.”

Inarguably, hip-hop has been at the center of American popular music, if not popular culture, for decades. “Hip-hop has overshadowed other types of music for years,” says Wassim “Sal” Slaiby, manager for the Weeknd and French Montana. What’s new, he says, is that “streaming has made the music very accessible.”

Carl Chery, a former hip-hop journalist turned head of artist curation at Apple Music, recalls that “a few months ago, the president of a very successful label told me that there’s a revolution going on with hip-hop.” He lets out a laugh. “I’ve always felt that we were number one, but maybe some of the metrics were lacking. Now with streaming, there’s just no hiding it anymore.”

From the music’s earliest days, in the face of the predominantly white record business’s indifference or derision, MCs and DJs have had to be resourceful in performing, marketing, and distributing their music. “Hip-hop culture has always had the hustle and the grind,” says Slaiby. “I remember when artists were giving out mixtapes for free, or selling them for five bucks. Who else was going on the streets like that, trying to get their voice heard? That was the greatest hustle ever.”

“Back in the day,” reflects Don Cannon, a Philly native who discovered Uzi for Generation Now, “you did a thousand vinyls, that’s all you reached. You made ten thousand CDs, ten thousand people got it. You made a hundred thousand DAT tapes, then a hundred thousand people got it. Now I get a track to Spotify, Apple, SoundCloud, millions of people can hear it instantly.”

Hip-hop producers and MCs, who have historically earned far less money from live performance than rock acts, spend their days and nights in the studio, constantly tinkering with novel sounds and responding to the latest earworm making the rounds (cf. this summer’s Atlanta-based flute fad). Rock and pop acts tend to wait years between album releases, in order to tour the country or the world. That may be lucrative, but it has its costs in the streaming era. Says Interscope’s Manda, “Look at how Lil Wayne got hot. Look at how Gucci Mane got hot. Look at how Drake got hot. It was a frequent output of music. And if you keep putting out new music, it brings more people into your catalogue. The more music you put out, the more people you hook.”

Now that streaming has finally curbed piracy, “we have a growing business again,” says Tom Corson, president/COO of RCA. “That requires a different mind-set. That requires investment.” This year, RCA outbid multiple suitors to sign SZA to a seven-figure deal, just one of the multimillion-dollar deals struck this year by this wave of streaming-savvy hip-hop artists. “It’s definitely a seller’s market right now,” says Corson. “And if we are investing more heavily, there’s nothing wrong with sharing the wealth.”

A couple of years ago, Joshua Binder, a music attorney who represents Kendrick Lamar and SZA, began working with an Atlanta MC named Russ. “The kid was dropping a song on SoundCloud every week, and was able to get over 100,000 plays within a 24-hour period,” says Binder. “At first he was touring 500-person rooms, then 1,000, then 2,000. By that time there was a five-label bidding war over Russ. We ended up signing a ridiculous deal with Columbia Records,” which sources place at seven figures.

“The marketplace is fucking out of control,” says Motown president Ethiopia Habtemariam, citing recent bidding wars over cheery Cali rapper Kyle (won by Atlantic), woozy R&B singer A.Chal and Florida’s XXXTentacion, alleged owner of a disturbing criminal record for domestic violence in addition to 1.2 million SoundCloud followers. “I don’t want any part of that,” she demurs, “but I get it. They see the numbers.”

“A&R people who were trying to find the next pop diva or rock band five years ago are now trying to sign the next Playboi Carti,” says Manda. “Listen,” he continues. “I lived through Mumford & Sons and all that stuff. Now is the time for urban music.”

On a Wednesday in late August, Atlantic’s Julie Greenwald, rock-and-roll chic in a vintage Neil Diamond T-shirt tucked into a Gucci maxi skirt, is presiding over her company’s weekly streaming and sales meeting. Atlantic, led by Greenwald and co-chairman and CEO Craig Kallman, is now the top-ranked label in the business, based on market share, for the first time that anyone can remember. Kallman cut his teeth in the early ’80s as an NYC club DJ before starting his own successful dance and hip-hop label, Big Beat Records; Greenwald came up through Def Jam Records, where she ran point for everyone from Jay-Z to DMX. Theirs is a diversified roster that includes Ed Sheeran, Twenty One Pilots, Kelly Clarkson, and Sia — but more than anything, it’s Kallman and Greenwald’s belief in and feel for hip-hop that’s lifted Atlantic to the top of a famously competitive industry.

Greenwald realized early on that all the precise consumption data generated by streaming services, and shared with labels, would remove some of the guesswork inherent in discovering talent and marketing their product. “I used to market by gut,” she says. “I’d go to the barber shops and the nail salons. Now I actually know where the fans live, their age. I can be so much more efficient with our dollars.” She and Kallman have hired specific staffers to work the various playlist programmers at Spotify and Apple, as have most of the major labels. Universal Music Group brought on a former Genius editor named Andre Torres just to oversee urban catalogue. “This is music that was generally assumed had no shelf life,” says Torres. “But the streaming data is showing the complete opposite. Not only does hip-hop have a shelf life, it has more of a shelf life than rock and roll.”

The dozen sales and streaming executives gathered in Atlantic’s midtown headquarters, or conferenced in from L.A., have in front of them spreadsheets, sorted alphabetically, filled with streaming data on Atlantic’s urban artists. Most of today’s conversation centers around Atlantic’s two big summer breakouts, Cardi B and Lil Uzi Vert. Apple’s Carl Chery jumped on Cardi early, giving her prime exposure on the A-List: Hip-Hop playlist, and the numbers reflect that: For the week ending August 17, over half of “Bodak Yellow”’s 15 million streams came from Apple Music users. Without top 40 radio airplay, the song has gone to No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100.

As for Lil Uzi Vert, Greenwald makes prayer hands and gives thanks to the rap gods: His debut album, Luv Is Rage 2, is finally set for surprise release that Friday. It’s now been six months since Uzi uploaded “XO Tour Llif3.” Since then, it has been streamed over 1.3 billion times across audio and video platforms. (Industry sources estimate that the label will earn roughly $4.5 million from those streams, out of which Uzi banks over $900,000.) When the album drops, Basa will spotlight six different tracks from Luv Is Rage 2 on RapCaviar. “‘XO”’s not going away either,” he tells me the following week. “It’s still a monster.”

Goldman Sachs predicts that global revenue from music streaming will soar to $28 billion by 2030, and asserts that after nearly two decades of post-Napster misery, the three major records groups — Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group — are now dramatically undervalued. Still, questions persist about the viability of streaming as a stand-alone business. SoundCloud nearly ran out of money this summer before securing new financing, and in June, digital radio pioneer Pandora was forced to sell a 19 percent stake in its company to SiriusXM in order to stay afloat. Both companies were late in selling on-demand subscriptions, and as a result, both purged their CEOs. Meanwhile, Spotify will reportedly go public soon, as it raises money to further compete with two of the richest companies in the world, Apple and Amazon. The industry is hopeful that Amazon in particular can help bring in the soccer moms, classic-rock dads, and country fans who are underrepresented among today’s music streamers.

Until then, though, “it’s all about hip-hop,” says Lamar attorney Binder. “There is just an insatiable appetite for it.” With “Look What You Made Me Do,” Taylor Swift has the new No. 1 song on Billboard’s Hot 100, but on the Billboard 200 chart for the week of September 16, the No. 1 and No. 2 albums are, respectively, Uzi’s Luv Is Rage 2 and, in a mild surprise, XXXTentacion’s 17, an independent release that outsold (meaning outstreamed) the first Queens of the Stone Age album in four years. And as for Moneybagg Yo? Basa tells me he’s placed his songs on a number of playlists, including Most Necessary, and they’re performing well. So what about RapCaviar? “He’s not on there yet,” says Basa, “but it’s like watching a college football player you know will make it to the NFL. He’ll get there. I can tell.”

The RapCaviar Effect

The songs and artists currently featured on the hit-making playlist — and what that means for them.

“I Get the Bag”

Gucci Mane, feat. Migos

This collaboration between Mane and Migos (the latter having released “Bad and Boujee”) has hit 4 million weekly streams.

“Bank Account”

21 Savage

The Atlanta rapper released his debut this year; this song reached No. 4 on Spotify’s weekly Top 200.

“X”

Lil Uzi Vert

Lil Uzi Vert has four songs currently on RapCaviar, including this and the hit “XO Tour Llif3” (see below).

“Perplexing Pegasus”

Rae Sremmurd

This duo from Tupelo, Mississippi, also had the 2016 hit “Black Beatles,” which reached No. 1 on Billboard’s “Hot 100.”

“Roll in Peace”

Kodak Black, feat. XXXTentacion

Black’s collaboration with controversial rapper XXXTentacion currently has over 8 million YouTube views.

“Fuck Love”

XXXTENTACION

One of two XXXTentacion songs now in Spotify’s Viral Top 50; the other is “Jocelyn Flores.”

“Love Scars”

Trippie Redd

Rapper-balladeer Redd’s “Love Scars” has notched 8.5 million YouTube Views; he’s yet to release an album.

“XO TOUR Llif3”

Lil Uzi Vert

Lil Uzi Vert’s nonsensically titled hit won Song of the Summer at the recent 2017 MTV VMAs.

“Butterfly Effect”

Travis Scott

Travis Scott is the stage name of Jacques Webster Jr., who’s now famous enough to have made a cameo on Ballers.

“Bodak Yellow”

Cardi B

A breakout anthem from the Bronx-born reality-TV star that’s just surpassed 120 million YouTube views.

“No Complaints”

Metro Boomin

This St. Louis rapper’s latest mixtape, Perfect Timing, hit No. 7 on Billboard’s “Rap Albums” chart.

“Rake It Up”

Yo Gotti, feat. Nicki Minaj

This single from rap veteran Yo Gotti peaked at No. 10 on Billboard’s “Hot 100,” the best showing of his career.

“No Flag”

London on da Track

London on da Track is a 26-year-old Atlanta producer; “No Flag” hit No. 3 on Spotify’s weekly Viral 50.

“Magnolia”

Playboi Carti

A.k.a. Jordan Terrell Carter, he released his first mixtape in April; “Magnolia” now has 25 million YouTube views.

“1-800-273-8255”

Logic

Logic’s anti-suicide anthem reached the No. 1 spot on Spotify’s Daily Top 200, edging out Taylor Swift.

“Batman”

Jaden Smith

A new single from the son of Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith that just passed 1 million YouTube views.

*A version of this article appears in the September 18, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.