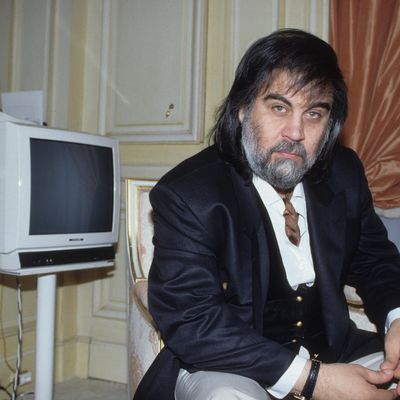

This story originally ran on October 5, 2017. It is being republished today on the occasion of Vangelis’s death at 79.

When actor Rutger Hauer said “You can only be a genius so many times in your life” to close Kenneth Turan’s great 1992 Los Angeles Times account on the making of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, he was not specifically addressing the Greek composer, Vangelis, who created the film’s score, though he could have been. Hauer, the man who portrayed one of the movie’s villains, the replicant Roy Batty — and, less famously, wrote some of its more memorable lines of dialogue — was addressing how the project, once considered a financial and creative failure but which history has judged among the most culturally influential films of all time, brought something special out of its many participants, including Vangelis, whose electronic music is a pillar of the film’s mythical reputation. Ever since its June 1982 release — when Blade Runner was bombing at the box office, leaving a trail of underwhelming critical response and surreptitious Hollywood backbiting — consensus has been that Vangelis’s contribution was inspired.

Blade Runner didn’t make Vangelis’s career. Evangelos Odysseas Papathanassiou was already a progressive-rock stalwart — and newly minted pop star. He’d established himself with his late ’60s/early-’70s band, Aphrodite’s Child, as well as nature documentary scores for French director Frédéric Rossif, and ensuing solo albums built on his mastery of a then-novel instrument called the synthesizer, playing music semi-accurately identified as New Age. In Vangelis’s case, it was less genre than worldview. Applying a slew of keyboards at his London studio, Nemo, he filtered prog’s pomp, ambient music’s open melodic space, and the percussive ethno-ambience of what would soon be dubbed world music, through a composer’s perspective. Many of his results were not dissimilar from the Krautrock experiments of bands like Can and Cluster, enlightened-cum-damaged art-school Brits such as Eno and Peter Gabriel, or — at his most overbearing — ELP and Yes (Vangelis recorded with Yes’s Jon Anderson on multiple occasions). Judiciously parsed, it is a body of work that — alongside Kraftwerk’s catalogue — helps paint an important European prehistory of techno.

On the cusp of Blade Runner, Vangelis was enjoying a period that saw his decade in the shadow of Europe’s mainstream step out into the neon sunshine of the American market. Disco in general, and Giorgio Moroder’s productions in particular, had integrated synthesizers into the Hollywood palette, and, as Vangelis’s work evolved, it led to two huge commissions. First came the 1980 score of the hit Carl Sagan PBS mini-series, Cosmos, which featured new theme music and incorporated various older recordings. Then, more significantly, came the soundtrack for Chariots of Fire, Hugh Hudson’s period piece about British athletics and prejudice, which in March of 1982 won Vangelis an Oscar for Best Score, and whose theme song went No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 a couple of months later.

Blade Runner was a different beast. Scott and Vangelis had collaborated previously on a Chanel advertisement called “Share the Fantasy,” one reason the director invited the composer to view a rough cut of the unfinished film. Work officially began on the score at Nemo in December of 1981, with Vangelis receiving footage from the editing room on VHS tapes, scene by scene, then processing the visual inputs and cues, creating live takes using the dozen or so synthesizers at his studio. This immediate integration of sounds and vision was key in making the music responsive to the unfolding scenes and the atmosphere Scott had created. They were not simply connected through aesthetics or the call-and-response of the narrative, but through a shared emotional tonality and fully cohesive sensual environment: just cold enough to be artificial, just feeling enough to be alive.

Melodrama that could saddle Vangelis’s other works with cheap romanticism was toned way down — with only Dick Morrissey’s faux-noirish saxophone on the film’s “Love Theme” approaching a traditional saccharine moment. Otherwise, the spare Yamaha CS-80 synth lines — by turns, august and sweet — revealed a complex stillness, a set of detached passions attempting to rebuild themselves, a desensitized state searching for soul. More simply put, the music declared that “the future is old.” This idea — written down by Carl Jung in his Red Book, and often applied by Philip K. Dick (whose 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? of course became the basis for Blade Runner) — was one of Scott’s reference points in the making of the film, and a pocket proverb to a century of dystopian visions.

This future was also foreign — or, more to the point, polyglot. Here too, Scott’s vision of Los Angeles 2019, its pidgin tongues, customs, and cuisines, overlapped with Vangelis’s idea of New Age; and the latter’s comfort at incorporating global folk cultures into his machine music, created a juxtaposition at once more realistic and inexpressible of what lies on the foreseeable horizon than any prior sci-fi. It is not by coincidence that one of the soundtrack’s most striking pieces is entitled “Tales of the Future,” a gorgeously dark hymnal featuring the qawwali-like vocals of Vangelis’s Aphrodite’s Child colleague, Demis Roussos. Though the music girds a scene where the blade runner Deckard hunts down the female replicant Zhora, in its timbres, its psychological profile, and its pulse, it could not sound less like a soundtrack for a search. More like a Middle Eastern funeral.

When the Vangelis score was finally officially released in 1994 — after a protracted disagreement with the producers that (coincidentally?) lasted as long as it took for Scott’s original edit of the film to finally be released — “Future” was pinned near the album’s back, alongside the closing credit music, which not only sounded like a chase, but like a whole other kind of “jam.” Just as Blade Runner gained a new life in the budding movie-rental market, the concurrent, abundant creation of cheap synthesizers and drum machines (many of them Japanese-made) helped power new electronic musical exploration in myriad urban centers where synthetic rhythms presented an escape route from modern life. Despite its availability only on the film’s VHS or laser-disc releases, Vangelis’s Blade Runner music became a lodestar, marking a course open to individual interpretation. So, young British electronic composers saddled up to the analog ambience and knowing artificial playfulness of Vangelis’s deep trove of synth banks; Detroit’s techno rebels gravitated toward his symphonic, mechanized dread, while armies of experimental producers jocked his mix of sonic textures and juxtapositions. By 2008, when Massive Attack and the Heritage Orchestra collaborated on a live performance of the score at London’s Meltdown Festival, Vangelis’s Blade Runner felt as much a part of the 20th-century electronic canon as various Philip Glass and Steve Reich pieces, its restless genius still searching for more life.