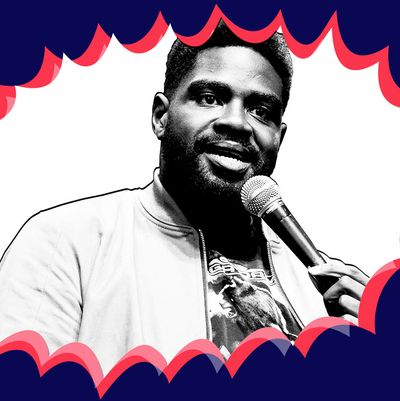

I love it when a line from a joke gets stuck in my head like a song lyric. There probably wasn’t a week in the ’90s where I didn’t think of the way Chris Rock said “big piece of chicken” on Bring the Pain. More recently, I’ve spent the last five years thinking about how John Mulaney says “push him” on New in Town. Almost all of Ron Funches material has that quality. It’s a credit to his word choice, and the magical superpower that is his voice. It is, for my money, the best in the business. And there might be no better example of its use than his masterful joke “F*ck Linda”:

That joke and that voice is the subject of this week’s episode of Good One, Vulture’s podcast about jokes and the people who tell them. Listen to the episode and read an excerpt from the transcript of the discussion below. Tune in to Good One every Monday on Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Do you listen to your sets afterward?

At my best I am. When I’m in my zone I am. When I’m touring I will listen to the set back then, but I hate it.

Of the many things that seems particularly hard about being a comedian is that you have to listen to your voice is up there.

It’s the worst. It’s the worst. It feels bad. Everybody’s always like “I love your voice” and then I hear my voice back and I’m like, Uuughh I sound like a whiny child. It’s difficult, but it’s like looking at yourself like an athlete. No athlete worth his salt wouldn’t go back and look at their game tape and see what they did wrong and what they could improve on.

How deliberate are you with how you use your voice? I ask because with this joke, the melody of it got stuck in my head like a song.

Not so much deliberate about it, as aware of it. I’m aware that my vocal patterns are a little bit off-kilter and that sometimes it can be singsongy. It’s just a mix of a lot of things. I moved around a lot: I’m from the Midwest and also the West Coast and there’s a little bit of southerness in it too. Then it’s also I had a speech impediment as a kid. It’s just like a lot of the things that people make fun of me for when I was a kid are turning out to be very beneficial for me now as far as being cartoon characters and things like that. But in my stand-up, I was just like, Oh this is my natural rhythm. I do try to make sure I hit certain words certain ways to get the most impact, but mostly it’s me being conscious to break that rhythm, especially if I’m doing a longer set because at my best, people are falling into my rhythm. They’re in it and they’re laughing, but if longer than 10, 15 minutes in the same rhythm, you sort of get sleepy. It’s like brainwashing.

I have to imagine this joke is the slowest delivered one you have because a lot of the joke is the pauses. Did that just come out from performing it?

Yeah. I was taking a lot of acting classes, so it helped me in my acting things out and taking more time and getting laughter off of different features. Not being so word reliant. For this joke, I knew there needed to be suspense as far as leading you one way and turning it another. I lead you one way like, “Oh guys, guess what I saw. I saw a horrible thing. This guy. Can you you believe this guy? He’s so rude.” And then it’s like, “Oh I’m just playing. What about this. What if he’s nice. He’s a nice guy.”

You’ve done this on television. You’ve done it on your record. What’s it like to stand there and wait. Especially during the part when you say “he needs to remind himself,” what’s it like to sit in that pause?

It’s amazing because it’s like they’re an animal and I have a little trap and they’re walking towards it, and I see him and I know if I just stay very, very quiet and don’t move I’m about to catch them and get dinner. I don’t know what that feeling means. If it’s like hunting or what it is. But it is like a Cheshire cat where I’m just like, “I got you.” That’s my favorite. Especially once I’ve done it a ton of times. I know where I’m going.

I’ve heard you talking about liking Tig Notaro and liking Todd Barry, two famously slow comedians. What do you think you got out of seeing them as comedians that do something similar to what you ended up doing?

I just got the ability to accept myself. I saw Tig at Bumbershoot and she was just pushing her little stool around. The crowd was very loud and talking over most of the other comedians and she just kept getting quieter and quieter and quieter until they had to listen to her. That was the point where I was like, Oh, I can be me. I can be quiet and still be powerful. It was just something I had to accept. Before it was just like, Oh, if I’m going to be powerful I have to be like pow! Be loud. Be in your face. Be energetic. I was like, Oh, I can just be my weird little self and I’ll be fine.

Being a wrestling fan, do you feel like your giggle is your comedic finishing move?

It’s helpful. I’ve been tempted before to be like, Oh, that joke didn’t work, how about I just giggle my way out of it. But it just reads as phony and I never want to use it as a crutch. Because I never want to have to stop giggling, because I like it and it’s who I am. I don’t want people to be like, “Oh, that’s his schtick! He just goes up and tells mediocre jokes and giggles after!” But people like that I’m having a good time and apparently they like my laugh. So why would I not use a tool that I have as long as it comes out naturally.

In this joke, like a lot of your material, you play with contrasts. How did that push and pull develop?

It started with just being aware of how I viewed myself and how other people viewed me. At first, I could hear my voice and I knew my tones. I’m like, I’m a sweet little boy. And at the time, if you’re 320-pound black dude, you looked scary to some people. So I had to play with both of those things and play with people’s perspectives of me and what they saw up-close. It was a lot of the jokes about laughing like a Japanese princess. Some of those things have changed recently and I have to adjust, especially because I lost like 140 pounds.

Just playing with people’s perspectives is always something I’m interested in. I had a mentor in comedy who was like, “Man, women like your jokes. Write towards the women and dudes will follow. Why would you write towards dudes — they’re done.” I end up with a lot of women who like my act, which I love, because usually they’re smarter. I realize the rarity of being a man who goes up there and is like, “I love British Bake Off! I Love Rupaul’s Drag Race! I love all these things!” And women after shows will be like, “We don’t even get really that many women comedians who talk to us about the things that I like too.” I know that not all women like these things, but a lot of things that I liked ended up appealing to women. And then my girlfriend was like, “Well, you’re also cute.” And I’m like, “Thank yoooouu.”

Considering this, what is your history with masculinity and toughness?

I do play with that a lot, because that’s just how I grew up. I was raised by my mom and my sister and my aunt who had a daughter. There wasn’t another boy until I was 10, and he was 1. My mom had an abusive boyfriend who was very masculine, so I always saw these sorts of things as negative traits, very dominant traits, very oppressive traits. I always found real strength in — like my mom — the ability to survive and to not let them change your worldview. To have traumas happen to you and still be positive. To me, that was always true strength, to be like, “Yeah, that was shitty, but I’m still going to open my heart with someone new even though that person cheated on me.” That is what I want to play with in my comedy. What is really considered masculine and what should be. What type of man I want my son to be and what type of man I want to be.