The title of Joan Kron’s documentary Take My Nose … Please is creepily suggestive: a Henny Youngman–esque one-liner over a world of pain. The subject is plastic surgery; the subjects are women comedians, and their habit of mining their bodies for laughs. As The Substance of Style author Virginia Postrel points out, they were the first group to “own up” to their dissatisfaction with their looks and the first and loudest to proclaim their decisions to have surgery. Kron, who is 89 and spent 25 years as a contributing editor of Allure, leans toward the positive aspects of having “work” — nose jobs, face lifts, liposuction, Botox, whatever. But it’s a rough ride to that resolution. Early in the film, Margaret Cho nails both sides of the issue in her stand-up act, decrying plastic surgery as “brainwashing, mutilation, and manipulation of women.” Beat. “I’m still gonna get it, though.”

Kron’s strategy is to follow the lives, careers, and potential surgeries of two funny girls while weaving in bits of history and commentary and jokes, lots of jokes. I use the term “funny girls” advisedly, since one historical tidbit is that Funny Girl vaudeville star Fanny Brice — who made her name as an ethnic-Jewish contrast to the leggy Ziegfeld girls who’d perform alongside her — was later seen on the front page of the New York Times preparing for a nose job. The process was relatively new. It was just over a century ago, historian Paula J. Martin explains, that French plastic-surgery pioneer Suzanne Noël offered her services to women gratis, hoping to empower them in a world increasingly dominated by male, magazine-cover standards of beauty. She said she was liberating women from judgment. If only.

It’s scary to watch in this context of the routine of female comedians who became rich and famous making fun of their looks. Here are Ed Sullivan and Johnny Carson introducing one after another: Phyllis Diller being carried around by young men singing that she’s the most beautiful girl in the world. Totie Fields mincing to “I Feel Pretty.” Joan Rivers babbling jokes about her mother’s revulsion and disappointment. Fields, of course, lost a leg after her plastic surgery led to a blood clot, and Rivers … we know. (How did Diller spend the decades after her plastic surgery? I never saw that much of her when her subject stopped being her bad looks.) Amy Schumer’s celebrated Twelve Angry Men satire — in which schlubby males debate whether she’s hot enough to have her own TV show — seems, in comparison, blessedly sane. (It’s the men who are the fools.) Kron also samples Schumer’s astounding “Last Fuckable Day” sketch, in which several of our finest actresses are shown having cheerfully internalized the male-dominated industry’s insane double standards about female aging.

Kron’s protagonists, Emily Askin and Jackie Hoffman, both have Jewish noses they hate but are otherwise dissimilar. Thirtysomething Pittsburgh improv comic Askin reveals late in the film that she’s a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, and that her initial response was to gain 100 pounds to “protect herself.” Gastric bypass surgery helped her lose the weight and now (although she’s engaged to a man who says she’s perfect the way she is) she wants a straighter nose sans bump. (The above parenthetical is fascinating in itself. “You’re perfect the way you are,” her fiancé says, then adds, “But it’s not my life to live.” Either the women in the film don’t believe the men they’re with or one man’s regard has no bearing on how they see themselves — or how they perceive other people see them.)

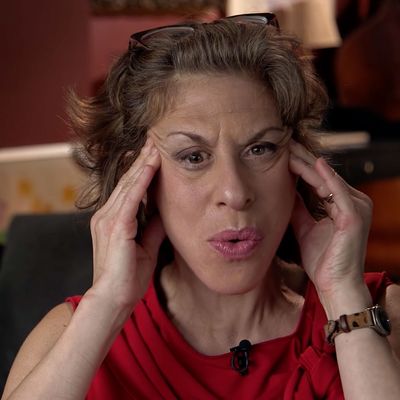

Fiftysomething comedian Jackie Hoffman you probably know. She’s referred to in the press as the “Queen of Self-Loathing.” Part of her act centers on jokes about her “ugliness.” (The film doesn’t mention a cringe-worthy arc on Curb Your Enthusiasm in which Hoffman’s character passes herself off to a blind man as a model, prompting looks of incredulity and disgust from Larry David and Ben Stiller when the blind man says, “Hands off.”) Hoffman makes fun of surgery onstage, but now … maybe she wants it. Maybe. Her looks have helped to give her a career. But maybe the pouches in her cheeks … or that nose.

Hoffman and Askin are delightful company and, in their one face-to-face meeting, dig into the differences between them. Askin thinks her nose job was an act of self-love, while Hoffman says that anything she’d do would be out of self-loathing: “It would be like, ‘If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.’” She says she hopes it would “transform her interior,” but doubts it. She also begins to see how once you fix one thing, you might be driven to fix another … and another … until it becomes an addiction. The issue of body dysmorphic disorder is raised. On an individual level, it’s tragic. On a collective level — our whole culture has a kind of body dysmorphic disorder — it’s obscene.

And yet that theme of “empowerment” pervades the movie. Take My Nose … Please won’t please people hoping Kron will settle on the view that plastic surgery is, as Margaret Cho says, “brainwashing, mutilation, and manipulation of women” without going on to the part where she says, “I’m still gonna get it, though.” Along those lines, I wish Kron had mentioned all the men (one of whom is in a very high office right now) who likely have pressured their wives (and, for that matter, daughters) to have surgery. It’s not so “empowering” then. I wish she’d also shown how the self-loathing can be turned outward, as in the ghastly stretch of time in which Rivers ridiculed Elizabeth Taylor — an icon of beauty when Rivers was growing up as a self-described “ugly duckling” — for gaining weight.

But as Askin’s fiancé says, “It’s not my life to live.” Kron and her nimble editor Nancy Novack have created such a sweeping, buoyant, and entertaining documentary that even as you wince and mourn and roll your eyes, you might be thinking, “I want that procedure.”