Before he had any taste in music Jann Wenner knew about the dynamics of being an editor. A curious detail in Joe Hagan’s biography, Sticky Fingers, is that the founder of Rolling Stone didn’t much listen to music until he saw the Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night. “In high school,” Hagan writes, “he was a fan of Paul Anka. ‘He is one of the two good singers that “rock n’ roll” has produced,’ Wenner wrote to his grandmother, ‘the other being Johnny Mathis.’”

But as an 11-year-old, he’d joined a couple of neighborhood kids in San Rafael, California, who were producing a mimeographed newspaper, named himself editor-in-chief, and changed the title from the The All Around News to The Weekly Trumpet. There were 64 subscribers and revenue of $5.97. Wenner hired his sister Kate as delivery girl, and refused her a raise. She quit and threatened to start a competing paper. “Oh yeah?” he taunted. “What are you gonna call it?” At boarding school — the Chadwick School in Palos Verdes, where his classmates included Liza Minnelli as well as the children of Glenn Ford and Yul Brynner — he became a sports reporter for the school paper, wrote a column on the school for the local weekly, and took over the yearbook, which gave him access to the school camera and an office of his own in an oversize closet. “I was the only person in the school who had an office,” he told Hagan. As a senior he engineered a takeover of the student council with himself as vice-president. His motive was to start an underground student newspaper, The Sardine, from the inside. “When he did The Sardine,” a classmate tells Hagan, “he had the school at his feet.” The paper might look familiar to Rolling Stone readers: the gossip column was called “Random Notes.” The administration shut it down after three issues.

At Berkeley, Wenner reported on the growing campus counterculture for San Francisco magazine and NBC News — he’d started working for the network as a traffic reporter for the local radio affiliate — playing up his role to the point where the head of NBC News in Los Angeles issued a memo: “Jann Wenner is not a correspondent. He is not a reporter. He is not a field producer. He is a campus stringer.” For the student newspaper he wrote a column called Something’s Happening under the pseudonym Mr.

Jones. Lifting his monikers from popular song — in this case, Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man” — was another part of the blueprint for Rolling Stone.

At a Grateful Dead show in a Berkeley gym, Wenner met the San Francisco Chronicle nightlife columnist Ralph Gleason, a jazz connoisseur and recent convert to rock fandom — and it was Gleason who recommended Wenner for a job as editor of a biweekly supplement to Ramparts magazine, the Sunday Ramparts. It was the fall of 1966, and Wenner had dropped out of Berkeley and spent a summer in London. He’d tried starting an LSD business, working as a wedding photographer, and performing as a folk singer (“I played one solo gig at some restaurant, sitting in a corner for the evening,” Wenner tells Hagan, “and I’m sure I was boring; made 15 quid or so; that was the end of the professional career.”).

Wenner lacked confidence as a writer, especially as a rock critic; he’d attempted to write a novel, a fictionalized account of his Berkeley years called “Now These Days Are Gone,” but found he had no talent for it.

What he excelled at, as they call it in the business, was packaging. In the case of Rolling Stone, one way you could look at the package is as a combination of Ramparts and a high-school yearbook, but with the editorial focus trained directly at the counterculture and the music underground, which Rolling Stone would deliver to the mainstream.

Ramparts had started in 1962 as a Catholic journal publishing meditations by Thomas Merton, but by the time Wenner arrived it was a glossy of the New Left, opposing Vietnam (the editors’ burned draft cards featured on one cover), publishing a column by Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver, and running exposés on the CIA, the Congress for Cultural Freedom, and the FBI’s COINTELPRO infiltrations of the student movement. (The magazine’s story is told in Peter Richardson’s excellent 2009 book, A Bomb in Every Issue.) Its editor was Warren Hinckle, a hulking 28-year-old who wore an eye patch and constantly courted controversy. Though he was only eight years older than Wenner, a generation gap separated Hinckle from his younger staffers. He was a heavy drinker with serious aspirations who looked down on pot-smoking hippies, and he pulled the plug on the Sunday Ramparts after a few months. But Wenner acknowledges the debt to Hagan: Hinckle, he tells Hagan, “transformed the magazine from a lefty, radical, Catholic magazine to a much more commercial, broader, muckraking publication. It was a breakthrough magazine of its time. And in addition to the tough political and cultural writing it was elegant … The mix was highly unusual. And that mix moved into Rolling Stone.”

More than the mix was borrowed: Wenner would print the first issue of Rolling Stone on unused paper stock from the Sunday Ramparts, employing its printer (which provided rent-free office space in an upstairs loft space), mimicking its layout (though with an original logo from psychedelic poster designer Rick Griffin), employing its production designer as art director, and using its office to make Xeroxes. It had been at the Ramparts office that Wenner met his future wife Jane Schindellheim.

In the summer of 1967, Wenner took part in the planning of the Monterey International Pop Festival, and was approached by the band manager Chet Helms to be the editor of a new “hippie music magazine” to be called Straight Arrow.

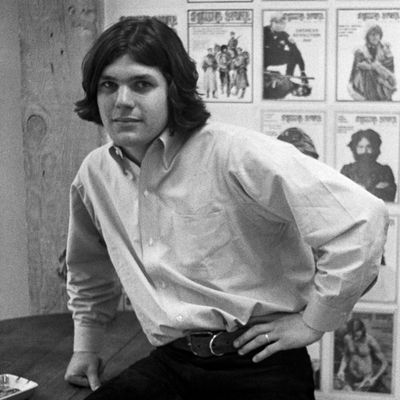

Funding for the magazine fell through, but Wenner walked away with the idea and a mailing list of potential subscribers from a local radio contest. He gathered his own funding from friends and relatives, among them his girlfriend Jane’s parents, and started Rolling Stone (the name was Gleason’s idea) with $7,500. He was 21 years old. Years later Jane Wenner would bump into Helms minding a San Francisco ice-cream counter.

Hagan’s biography is a colossal achievement of reporting and synthesis, fast-paced, compulsively readable, and consistently insightful in its understanding of how and why Wenner was able to turn a modest fanboy tabloid into an iconic cultural force and, after its golden years were behind it, to convert its waning and increasingly nostalgic cultural cachet into a media fiefdom that nearly made him a billionaire. The crucial element was Wenner’s relentless identification of himself with his magazine and the generation it gave a voice. He hired talented editors, writers, photographers, and designers and gave them lots of leeway, but he always reasserted his own control when they asserted too much independence, as in the case of a purge of firings and resignations in the winter of 1970, after disputes involving credit over the magazine’s coverage of the Kent State killings, putting the umpteenth shot of Mick Jagger on the cover, or whether to run a picture of Dylan receiving an honorary degree from Princeton. Wenner courted various benefactors, among them record company executives and the Xerox chairman Max Palevsky, but often bit the hands that fed him, constantly skirting bankruptcy but walking away with the reins to the magazine. Hagan makes sense of why Wenner infamously turned down a stake in the nascent MTV. In addition to being a skeptic of the enterprise (he thought it sounded like little more than a whole channel of American Bandstand), he would have, in the final negotiations, had to enter a merger that would leave him with a one-third stake in the joint venture but without control of Rolling Stone.

Hagan and many of his sources call Wenner a social climber and the point is so obvious to be beyond dispute. Wenner himself said he started Rolling Stone to meet John Lennon, and Hagan asserts that, just as much, he wanted to be John Lennon. In this, he came as close as any magazine editor could and certainly closer than any future editor ever will.

Mick Jagger gives Hagan the most sensible analysis of the intersection of Wenner’s role as editor and publisher with his social life among rock stars: Between friendship, business, and fame, sometimes your agendas align. At times stories of Wenner’s drug use and his sex life (his marriage to Jane was essentially open, he slept with men and women, came out as gay in 1995, and is married to the fashion designer Matt Nye) threaten to overwhelm the story of his career until you realize that his professional and social lives were always inseparable. None of it is a big surprise. His professional life made his social life possible and his social life for better or worse defined his instincts as an editor.

His forays into national politics and Hollywood were largely dead ends. Politically he gave voice to leftist writers but craved to belong to the Establishment, as indicated by a 1976 Richard Avedon photo portfolio of the Washington elite, glamorizing Donald Rumsfeld among others. When Hagan recounts the staff of Rolling Stone turning up their noses at an office screening of the 1985 film Perfect — a dramatization of a Rolling Stone series on the rise of fitness clubs starring Jamie Lee Curtis as an aerobics instructor, John Travolta as a reporter, and Wenner as his editor Mark Roth, a version of himself — it sounds like one of those obligatory scenes in an Adam Curtis documentary when Jane Fonda turns from radical politics to stationary bikes. This is the moment when the baby-boomers turn from idealism to narcissistic materialism. Hagan quotes what he calls Wenner’s “magnum opus,” a forward to Jean Pigozzi’s photography book Pigozzi’s Journal of the Seventies:

What we are about to look at is a world that turns around the new jet-setting, where room service is a fact of daily life and where it is important to be rich, any way you can get there and any way you care to define it.

People have mistaken their concept of the Seventies on the years ’74, ’75, and ’76, a time in which it looked like nothing was happening and life was boring. (I believe the Seventies didn’t begin until 1977, and that the Sixties finally ended in 1974.) We can start to understand the years that really are the Seventies as a reaction to boredom: an attempt to substitute something, to divert ourselves, to get some amusement and distraction. The real Seventies was a period in which the post-Sixties search for meaning was found to be pointless and premature. It was a time of rejection of meaning, during which it is better to be somewhat foolish and famous and fun—rich, if you will—than mope around, bemused or blameful, about the accustomed quietude.

One of Wenner’s refrains in talking to Hagan is that he isn’t a sellout because there’s no such thing as selling out. It’s a rationalization he shared with his generation and one the next generation could sniff out in his magazine, which is why in the 1990s we preferred Spin. Yet if you cared about rock music, you still had to read it, and if you played it you still had to go on the cover — as Kurt Cobain did in 1992, wearing a T-shirt that read CORPORATE MAGAZINES STILL SUCK in magic marker. Hagan is good on the writing in Rolling Stone, though it’s rarely central to the biography because Wenner’s managing editors have always tended to handle the talent. It’s stunning to learn that Wenner alienated Robert Christgau early on with this rejection note: “The first page is all about Bob Christgau, Esquire reviewer, late of a college education, a man of renaissance tastes, elegant opinion and high tone critic of ‘secular music.’ I mean, baby, who cares and is it true anyway?”

It would be decades before Christgau wrote for the magazine again. Greil Marcus left for years after the purge of 1970. Wenner largely lost his star critic Jon Landau, recruited from the pages of Crawdaddy!, when he became Bruce Springsteen’s producer in the mid-’70s. Wenner would lose his star photographer Annie Leibovitz a decade later, when he refused to share her with the relaunching Vanity Fair. (Hagan’s copious material about Leibovitz suggests she deserves a doorstop biography of her own.) Hagan argues that the magazine’s best years were from 1971 (with the arrival of Hunter S. Thompson, who’d been writing for Hinckle’s short-lived Scanlan’s Monthly) to 1977 (when editorial operations were moved from San Francisco to Manhattan).

I remember as a teenage Rolling Stone subscriber reading through a shelf of Thompson’s books that he considered the move to New York and a corporate, cubicle-filled office space to be the magazine’s death knell. Thompson’s prime with the magazine had already ended, the result of his foil and best enemy Nixon leaving the White House and his own increasing drug use, in Hagan’s telling. Just before Thompson’s suicide in 2005, Wenner had commissioned a profile of the writer — now using a walker because of a bad hip replacement; drug dependent from the moment he woke in the morning; failing in recent years to deliver on assignments for Rolling Stone but writing columns for ESPN that amounted to self-parody — that would portray him as “a huge degenerate junkie.”

By this time Wenner had reached his peak of profits as a publisher. Though the magazine had always afforded Wenner and his wife a glamorous lifestyle, Rolling Stone was a teetering business proposition throughout until the mid-1980s, when improved marketing techniques and synergy with MTV resulted in profits of tens of millions a year. He bought a $6 million Gulfstream II jet to cart celebrity pals around in the air. “Then it became,” Wenner tells Hagan, “‘What can we do to fly this thing? Where can we go? How can I take it in the air? I would just circle over LaGuardia to have lunch.’” But it was the 2000 conversion of Us, founded in 1977 by the New York Times Company and purchased by Wenner in 1986, from a monthly glossy to a weekly scandal sheet sold at grocery-store checkout counters that brought Wenner close to being a billionaire. Famously an internet skeptic, Wenner had made a small investment in Akamai Technologies, a cloud-computing platform, and when it went public in 1999 he made $35 million, which he invested in Us Weekly. The magazine (where I worked as a copy editor in its first months as a weekly) struggled initially, relying desperately on covers about celebrity weight loss, but after Bonnie Fuller was installed at the helm and instituted the “The Stars — They’re Just Like Us” formula, Wenner was making a profit of $1.75 per issue sold at the newsstand, to the tune of $90 million a year.

His mistake was to buy back the half of Us Weekly he’d sold to Disney during its faltering inaugural year by taking out a $300 million loan in 2006. “For the next two years,” Hagan writes, “Wenner would pay back nary a dime of the Disney loan, funneling all the profits directly into his lifestyle.” After the crash, the loan was renegotiated on onerous terms, and a decade later Us Weekly and Men’s Journal have been sold to National Enquirer publisher American Media, the Gulfstream is a thing of the past, and Rolling Stone — turning 50 and still plagued by libel issues from its 2014 story about campus rape — is on the block. It’s tempting to blame the magazine’s fate on the death of rock and roll or the rise of the internet, but in Hagan’s account it’s the upshot of one publisher’s all-too-typical taste for debt financing combined with a singular and admirable determination to retain control of the magazine he started. Wenner has broken with Hagan, calling his biography “tawdry” and bemoaning its lack of emphasis on his generation’s “creativity.” He’s wrong about this — the tawdriness goes with the territory and the creativity is on ample display (even if sometimes it’s embarrassing: Wenner gave Billy Joel the title line to “We Didn’t Start the Fire”) — and if Wenner’s history of breakups and makeups are any indication, it won’t be long until the two neighbors are brunching again in the Catskills.