Over a year ago, in an era long past, I began inquiring into the matter of the apocalypse. It is important to remember that it was still possible, way back in the early autumn of 2016, to reflect upon the end of the world as an abstraction. I had decided that I was going to write a book about apocalyptic dread — about, among other things, its various manifestations in contemporary culture, as well as my own anxieties (as a father of a 3-year-old, and more generally as a human being) about ecological catastrophe, the instability of globalized economic systems, the prospect of nuclear devastation, and other sources of general bad vibes.

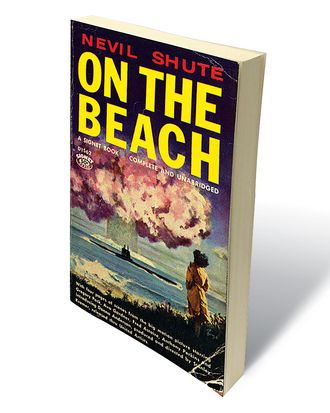

The project required a cultural diet of raw apocalypticism. For me, a typical day might have involved kicking back with a film about the end of the world — a Take Shelter, say, or a Time of the Wolf — before curling up with a fictional cataclysm like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach, in which a group of Australians, among the last living humans, calmly fill their final days as they await the southward drift of nuclear fallout. As troubling as this topic was, it was possible to keep it at arm’s length, to encounter it at the level of abstraction. Then, one year ago, around the second week of November — for reasons it is not necessary to reiterate — the apocalypse came to seem significantly less abstract.

Since then, my project has taken on a more dire and immediate aspect. When I watched, for instance, Snowpiercer, a post-apocalyptic action film in which a small contingent of humans survive on a train that circles the globe, with the super-wealthy living in luxury at the front and the poor in abject squalor in the back, it seemed less an extravagant social allegory than a plausible forecast of the near future. Yet it’s worth reminding ourselves that we are by no means the first generation to imagine ourselves as the last. “Almost sixteen centuries ago,” writes Annie Dillard in For the Time Being, “Augustine looked back three centuries at the apostles and their millennialism: ‘Those were last days then; how much more so now!’ ” Dillard’s beautiful and confounding book suggests that the belief in our living through the end of history is also a delusion about the specialness of our own time. There is, however, at least one difference between traditional eschatology and the present moment. Fictional representations of apocalypse, from the wildly speculative to the tonally realist, tend to focus their attention on a single form of destruction: an asteroid or a deadly virus, but not both. These days, the apocalypse is almost hysterically overdetermined. It’s all horsemen, all the time. There’s no one thing: It’s everything.

In The Sense of an Ending, the literary critic Frank Kermode wrote that our obsession with apocalypse “reflects our deep need for intelligible Ends. We project ourselves — a small, humble elect, perhaps — past the End, so as to see the structure whole.” Apocalypse, after all, in its original Greek means only this: to uncover or disclose, an act of final and absolute seeing. I understand this and feel it to be true: that imagining the last days, and ourselves as living them, is a time-honored way of making sense of the world. But over the past year, bearing that historical context in mind has not been easy. With the ascent to power of a former real-estate magnate–reality-television star and the violent escalation of the forces that churn in the air around him — the curdled nationalism, the naked racism, the climate denialism — my relationship to my subject has changed.

There’s a numbness that sets in — the sense that everything is terrible, always, and it’s difficult to imagine a future in which it’s anything but worse. And it’s a numbness that manifests itself not in despair but in ironic distance. Twitter is a reliable real-world source of this particular mood. Dipping into my timeline recently, I found an Atlantic article about how with the North Korea crisis, “the possibility of nuclear war has suddenly become discussable — and not just theoretical,” and then an AV Club article about how “clear-knee mom jeans” are the “latest sign of impending apocalypse.” The platform itself, in its prioritizing of the immediate and the sensational — its tendency to funnel attention toward the worst available realities, and to reward pithy reactions to same — lends itself to a kind of ambivalently ironized terror. The message, basically, is this: LOL we are all completely fucked. And it’s never wholly clear, to me at least, whether the irony is a defense against the sense of our complete fuckedness or the manifestation of a belief that we might be immune to it — that it’s not really real. Perhaps it’s both at the same time.

*This article appears in the November 13, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.