When writer-director Dee Rees debuted Mudbound at this year’s Sundance Film Festival in January, it came as a welcome shock to those of us who’d fallen in love with her tiny, intimate debut feature, Pariah, in 2011 — it was just such a leap of scope and ambition. With Pariah, Rees explores her own coming of age as an African-American lesbian through Adepero Oduye as a Brooklyn teen going through a similar awakening. It’s small-scale and beautifully shot, and its dramas are about personal growth. Mudbound, meanwhile, is a sprawling southern epic about two families, one white and one black (the McCallums and the Jacksons), each made up of a married couple, a grandfather-type patriarch, and a struggling-for-purpose young man (Garrett Hedlund’s Jamie and Jason Mitchell’s Ronsel) trying to eke out a life in the literal mud of post-WWII Mississippi. It centers on the plight of women — one stuck in a passionless marriage (Carey Mulligan’s Laura), and one stuck on the wrong side of a service economy (an excellent Mary J. Blige as Florence) — plus PTSD, as the younger men return from war and become unlikely friends. Mudbound also delves into racism, as Ronsel discovers that the country he risked his life fighting for overseas still doesn’t see him as a full person.

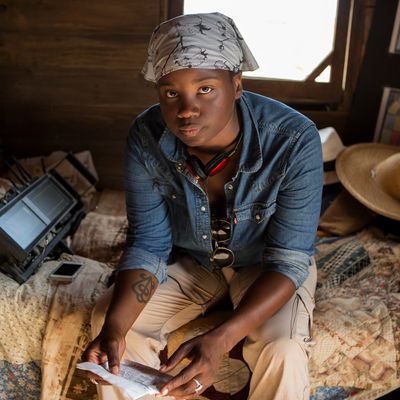

Mudbound is based on Hillary Jordan’s 2008 novel of the same name, and is only Rees’s second theatrical feature, not counting her Emmy-winning work co-writing and directing HBO’s Bessie. Rees joined the project both behind the camera and to infuse an existing script from Virgil Williams with her own sensibilities. We talked to her about her process, what it’s like to hang out with Mary J. Blige, and the racist joke she had to write.

On a practical level, how do you write?

I’m not a writer that writes every day. I just kind of have ideas. I jot them down when I have them and when I have enough, I just start. And for me I start more around noon and I’m all about feeling. Once there’s a theme I can’t not write.

I get everything out on index cards, whether it’s a phrase or an idea or a scene. And then my first step is to write longhand, because it’s a direct connection from your brain to the page, from your heart to the page. Then I type it up, and when I type that functions as the first edit, because when I’m reading that back I trim that down even more.

What’s the first thing you wrote?

I wrote poetry and short stories. I would send them to magazines, they wouldn’t get in. But short stories are how I found philosophy and how I’d understand the world. Filmmaking in general is my second career. I thought that writing wasn’t practical, so I went to business school and got an MBA and I worked three years in grant management. My first job was at Proctor and Gamble in Cincinnati, my second job was at a pharmaceutical company in Berkeley Heights, New Jersey. My third job was at Palmolive. And I realized, three jobs in three years, maybe it wasn’t the job. It had to be me. I wasn’t doing what I really loved to do, so I quit my job, went to film school at NYU, got an MFA, and just started over. All I knew was prose then. I didn’t write scripts until I got to film school.

How did you conceive of this screenplay?

This project first started for me in 2015. One of the producers, Cassian Elwes, had brought me the original script, written by this guy named Virgil Williams, and I thought there was a lot of there there, and that inspired me to read the book. Virgil and I never worked together; he just wrote the first draft and I rewrote the script for production. I really wanted to draw out some of the inner life more and to have the Jackson family [the black family] more rounded. I rewrote it so it was a story about two families who were connected in a way that they were reflecting each other. I wanted, on a bigger thematic level, to show how these families are all in the mud, they’re all connected to the land, and what it means to not be able to come home and what it means to the family around you.

The dialogue is incredibly thick and specific. How’d you get that down?

I’m from Tennessee, so that’s part of it. We had a dialect coach, so each of the characters is doing a different accent. Like the Jackson family, my grandmother is from Louisiana — they’re from Mississippi — but I was kind of able to draw on her sayings, her aphorisms and used those, and my dad and parents are from Tennessee, so I used all that and put it in. I kept a lot from Virgil’s first draft in terms of how the McCallans spoke. But I wanted to make sure Laura doesn’t sound like Henry. Laura is a bit more refined in ways, but Henry’s got an engineering degree. And Pappy [Jonathan Banks, the white grandfather] doesn’t sound like Henry [his son] because Pappy’s more ignorant. Like, I wrote the racist joke that Pappy says. It’s in the scene where Hap asserts that Ronsel is an officer in the military. And Pappy says, “What do you call a nigger with stripes? … A ra-Coon!”

Whoa. Why’d you feel it was so important to write that?

Because it gives dimension to the bigotry and illustrates how it’s manifested in a more nuanced way — not always menacing, but playful. Like, Pappy genuinely finds this funny and undoubtedly has a wealth of other “nigger” jokes stored up in his head.

I grew up in Nashville in the ’80s. So I heard tons of “nigger” jokes. Some told maliciously, others told by white classmates who didn’t see anything wrong in what they were saying. They were repeating what they heard their parents or sibling or friends saying. It was in some ways abstract to them, the dehumanizing aspect of it. Sometimes consciously connected to the black person standing in front of them to whom they’re telling a “nigger joke.” Sometimes strangely disconnected. There’d be the old irrational cop-out, “You’re not a nigger, but those other people are niggers.” Or the blatantly racist generalization or observation or anecdote, quickly followed by the weak verbal panacea of, “…no offense,” or whatever. But at the end of it all, “nigger” was a ready quiver in the adolescent white quill. It was a decisive fight-ender — or usually fight-starter — and a guaranteed gut punch that would momentarily stun or destabilize or rock the recipient. So I had that to draw from.

Do you see the industry as more receptive to black female filmmakers than when you started?

Not necessarily. No. I think it’s about taking time to build relationships, so the people I’m working with are people I’ve known since 2009. At the end of the day, I feel like it falls upon critics and audiences to talk about the work first and talk about the maker second. I think that when people are limited by the labels that are put on them, then that necessarily limits the perceptions of what people can do. So for me, excellence is excellence. If something is excellent, call it that. If something is mediocre, call it that. To me, if excellent work were celebrated and recognized, then it would go a long way toward acknowledging the people who make it and their capabilities. A time needs to come when what you see on the screen is undeniable.

This movie cost $11 million, compared to $500,000 for Pariah, but still not much money for how rich and layered it looks. What’s it like to get a low-budget movie about diverse storytelling made these days?

In a weird way, this movie was the easiest one to finance. The money was already kind of raised. So it was about what that meant in terms of production constraints. Originally, this would’ve been a much larger budget, but we couldn’t get it, so it was like, “Okay, how do we make it work?” That meant we had less days. I think we shot 31 days altogether, 28 days in Louisiana, 2 days in Budapest, and then we shot a day in Long Island at a WWII museum — that’s where we shot the B-25s on real B-25 planes. The budgetary constraints reflect how much time you get, but for me as a director, the thing I’m interested in are performances. So a bigger budget, at the end of the day, would’ve bought me more extras, but it wouldn’t have bought me more time. It wouldn’t have bought me those performances.

And then Netflix bought it for $12.5 million, in the biggest deal at Sundance.

It’s amazing, everyone’s investment is paid off and we made a film that looks like it cost twice that much. As an artist, you want your work to be seen, to be out there. So the idea that someone in Florida could watch this the same day as someone on Portugal is huge. When you talk about intersectionality and expanding the conversation, just being seen that broadly definitely does that.

For me I feel like my first film, Pariah, was kept alive because of Netflix. So to me I was happy to go with them because with Pariah, we did a small, limited release, but it didn’t get attention. And then it was on Netflix and people really knew about it. People to this day are still discovering Pariah, in the same way that I think Netflix is going to give Mudbound a legacy.

I think Mary J. Blige is a revelation. Why’d you want her as Florence, this proud wife and mother who has to serve Carey Mulligan’s character, even when her white husband is part of the reason her family isn’t advancing?

I wanted Mary for Florence because I saw Florence as being someone who saw everything and said little of what she saw. She had to be somewhat in her head and someone who had a reserve on the exterior, but on the interior had a lot of thought, a lot of light behind the eyes. Mary has that kind of vulnerability. If you’ve ever been at one of her concerts, it’s like a therapy session with 30,000 people. She’s not saying lines, she’s living every line, and that’s the same thing with her work as an actor. She living every moment. She’s not just kind of reciting. She’s really in it, really throws herself away and becomes the character. So I knew that she could go there, and just see this woman, see this life in her eyes. You see how when she’s with her husband she takes her hair down, but when she’s with the McCallans, she has her armor on. Mary pulls it off.

Do you still hang out with her?

We’ve hung out a few times. Mary’s such a cool open person, just a great spirit. It’s so great to be invited into her space. She’s someone whom I could text or email or call.

Are you leaning more toward movies or TV, post-Mudbound?

I’m casting another film that hopefully will shoot in the spring and then I have a couple of TV irons in the fire that I should know more about by the end of the year.

It seems like a lot of independent filmmakers are going to TV because it’s so hard to get low-budget movies made. I was wondering if that’s why you ultimately followed up Pariah with an HBO movie.

I want to get out of the independent film box. I just want to work in film, period. But after Pariah, I had all these ideas. I had this spec pilot I’d written about Nashville called The ’Ville. Ironically, I was getting people like, “No one wants to talk about Nashville,” and then a show comes out called Nashville on ABC a year later! Pariah opened doors that allowed me to always write, because after Pariah, Focus hired me to write another feature about a woman cop, that I wanted to do. They didn’t end up producing it, but because of that they asked me to write a pilot for a Viola Davis show. That didn’t go. But then HBO called me to rewrite Bessie, so I rewrote Bessie, and then they asked me to direct it. So Pariah definitely opened doors in that it kept me working as an artist. I never wasn’t working after Sundance 2011. I was writing things that didn’t get produced but I was always exercising that muscle the whole thing. It comes full circle. I was directing Bessie and that’s when Cassie reached out with Mudbound.

I didn’t know that your way into Bessie was rewriting it. Do you always envision things as a writer before you envision them as a director?

I got into this business because I wanted to tell stories. That’s what got me into filmmaking. I wanted to bring writing to life. To me, that was always the end. I wanted to create worlds and create characters that live on in people’s minds. and I wanted to be able to realize them. I always wanted to be an auteur. For me, I was open to doing adaptation, but I always wanted to do original work and create worlds and just create characters that would live on in people’s minds. I see it as all part of the same thing. Just to create something new.