How many readers of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son have wondered what happens to Fuckhead when he grows up? Johnson’s 1991 masterpiece — a lean and quivering book of 11 linked stories told by a barfly, a junkie, and a petty criminal whose voice is somehow older and wiser than his years — ends with Fuckhead sobered up and working at a home for the aged, demented, amputated, and otherwise infirm. He spends his days among the unwell who nobody else ever sees. His duties include making the patients feel human, touching them once in a while so they know they’re not lepers: “All these weirdos,” the book ends, “and me getting a little better every day right in the midst of them. I had never known, never even imagined for a heartbeat, that there might be a place for people like us.”

A tempting answer to the question of what happened to Fuckhead is that he became his author, who died on May 24, 2017, at age 67, of liver cancer. Sometimes the biographical fallacy isn’t a fallacy, and we know that Johnson spent a lot of his 20s in a haze of alcohol, heroin, and whatever else came his way. He quit drinking in 1978, at age 29, and his first novel, Angels, appeared in 1983. By the time of his death, he was the author of 19 books of fiction, plays, poetry, and reportage — one of which, the Vietnam War novel Tree of Smoke, won the National Book Award in 2007. He’s called a writer’s writer, but his audience is in fact legion. There are people walking around who know his books by heart. You probably know somebody like that.

Now there is a 20th and last book, The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, which Johnson finished just before his death. It collects five short stories, all of them death-haunted: “It’s plain to you that at the time I write this,” ends one story, “I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.” Two are told from Fuckhead territory — by desperate young men, one of them in jail, the other in a halfway house — and two are told by middle-aged writers with plenty of ghosts. These four stories rank with Johnson’s best work, but the title story, a catalogue of singular moments related by a man who tells us he’s passing through life as if it were a masquerade, ranks with the best fiction published by any American writer during this short century. None of these narrators is Fuckhead, but all of them, we suspect, could be. After all, we never learn his real name.

Salvation plots defined Johnson’s life and work — the rare American writer who worked in exile from the American Dream. Even William S. Burroughs wrote in reaction to that dream — with his rants against breeders and churchgoing folk — not simply apart from it. Stability, striving, homeownership, prosperity — when these things enter Johnson’s work (they hardly ever do), it’s as if by accident or as part of a charade. His characters live and die on the lonely fringes, on highways and in hospitals, in bars or behind bars, scavengers and hermits in the swirl outside the zone of American normalcy. The ones who hold a job or build a family seem aware that they’re doing so as if under cover, like the narrator of “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden.” Johnson himself knew there was something spectral about his own survival and his art. You can hear it in his titles: Resuscitation of a Hanged Man, Already Dead.

Within the spectrum of postwar American fiction, Johnson is hard to classify. He arrived at the end of the heyday of the Dirty Realists (among them his friend and teacher Raymond Carver), and his books had a harder edge, more liable to explode into violence. He garnered early praise from both Philip Roth and Don DeLillo, and while all three writers have their eye on the American berserk, there’s nothing in Johnson’s work like Roth’s relentless psychologizing or DeLillo’s probing of society’s secret systems. Like Marilynne Robinson, Johnson is a thoroughly Christian writer, but while Robinson’s novels are explicitly religious, it might be news to many of Johnson’s characters if you told them what they were experiencing was a crisis of faith or a conversion. It may even surprise some of his readers. Those approaching Johnson’s putative epic, Tree of Smoke, expecting a sweeping and integrated social novel that explains the country (the sort of book the writers of the generation that followed him — Jonathan Franzen, Jennifer Egan, Jeffrey Eugenides — are constantly attempting) will be disappointed. Rather than representative men and women, Johnson wrote about hard cases, freaks, and ghosts.

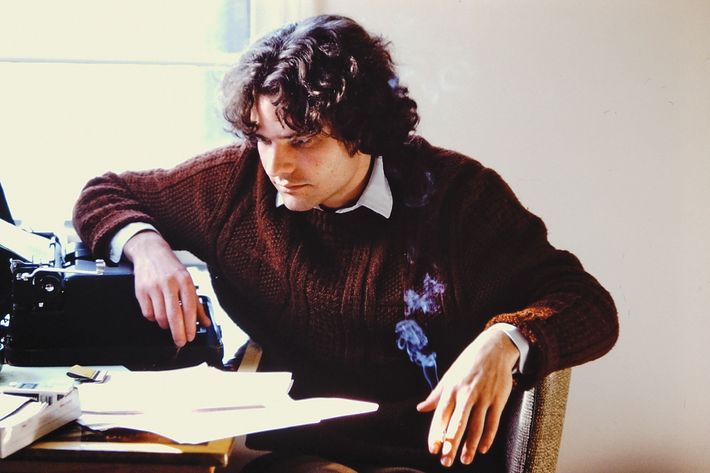

Johnson’s legend began with shades of an American Rimbaud. A first book of poems, The Man Among the Seals, appeared in 1969, when Johnson was just short of 20. These were the verses of a romantic teenager imagining his way beyond his years: “i would like to be just an old man with my gin,” one poem begins. An affinity for elemental landscapes (deserts, seas, wide horizons), a disillusionment with suburban life (televisions, detergent, mousetraps), and an intimacy with the bottle pervade the book. The 1970s were Johnson’s lost years. “I went from prodigy to prodigal in a hurry,” he told the New York Times in 2002. He took two degrees from the University of Iowa, where he studied writing and hit the bars with Carver. But becoming a writer requires more than an M.F.A. and a drinking habit. Johnson associated intoxication with inspiration, but his vices were an obstacle to writing. Hospitalized more than once for alcoholism, he also used heroin, though he was never a full-on junkie. “You can’t just go into a drugstore and say, ‘I’ll have some heroin, please,’ ” he told David Amsden in this magazine in 2002. “You have to be prepared to enter into all kinds of adventures that I wasn’t strong enough for.”

He wasn’t strong enough, either, to become a novelist. That took salvation, in the form of giving up drinking, and another five years. Angels set a template of dissolution, transgression, and redemption, in cinematic set pieces rendered in amped-up prose. These are the elements Johnson would modulate across genres in his fiction for the rest of his career. Angels is a love story that begins on a cross-country bus and a tale of crime and punishment that ends in the gas chamber after something like a jailhouse conversion. There’s a rape committed by a man in a red suit who could easily be confused with the devil himself. The climactic bank robbery is one of the prettiest scenes in all of American crime fiction. When the hero Bill Houston, until now a more or less likable deadbeat, murders a security guard, we see him for the holy innocent he is: “The smoke of gunfire lay in sheets along the air around his head, where light played off the fountain’s pond and gave it brilliance. In the center of his heart, the tension of a lifetime dissolved into honey.” What Johnson was doing wasn’t psychological realism, and it never would be. The damned and the saved lie someplace beyond what we call psychology. So do ghosts.

Angels began a quartet that looked at the shadow side of American life and found (or didn’t find) the cracks where the sun came in.

Characters show up across different books, and the country is seen through the lenses of various genres. Fiskadoro (1985) is set in a postapocalyptic Florida Keys, a corner of the country spared from nuclear devastation. Johnson said, “That book is America made bleak. If you take away the TVs, what’ve you got?” When you take the American Dream out of America, what do you have left? Tribes of weirdos living in huts on the beach decorated with parts from cars that no longer drive.

The Stars at Noon (1986) is a thriller set in Managua in 1984, narrated by a woman who passes as humanitarian, journalist, and prostitute; its Nicaragua is an amoral inferno of total duplicity. The hippie flourishes of Johnson’s prose till now give way to a truly hard-boiled voice. Fans of Sonic Youth will immediately notice in The Stars at Noon what appear to be allusions to Daydream Nation — “Does this sound simple, fuck you? Does fuck you sound simple enough?”; in fact, Kim Gordon wrote “The Sprawl” by raiding Johnson’s prose. If he wasn’t yet famous, he was seeping into the culture.

But the quartet finished with a dud. The intense, lyrical spell of Johnson’s early work is broken by The Resuscitation of a Hanged Man (1991), about a survivor of a suicide attempt who makes his way from Kansas to Provincetown, a medical-equipment salesman who finds himself in an unrepressed America and falls for a lesbian. He takes in drag shows and goes to church a lot. Religion moves from subtext to text. The prose is low-octane and for once hard to confuse with poetry. Three decades on, the story of a straight-laced Midwesterner entering a zone of licentiousness lacks any edge it might once have had. One of the hazards of wringing a novel out of the year you spent in a beach town on a fellowship is that it may be obvious you spent a year in a beach town on a fellowship.

Around this time Johnson’s life wasn’t entirely un–fucked up. A trip to the Philippines for Esquire yielded an unfulfilled assignment and a case of malaria. A second marriage fell apart, and the IRS was after him for $10,000. He was in need of saving again. This time it was his past that saved him. Jesus’ Son is a reimagining of Johnson’s wastrel years and seen through what John Updike called the “agreeable haze” of retrospect. The doubleness isn’t simply a matter of a narrator in and out of time: It’s also moral, a matter of spiritual questing.

In Christian terms, the junkie is the sinner pushed to the extreme, the saint inverted. Fuckhead’s questing sometimes gets confused with scoring a fix and the criminal undertakings (burglaries, shakedowns) that entails. “Fuckhead’s very hostile but at the same time he’s worshipful,” Johnson told the journal Columbia in 1993. “He displaces his hopes by attaching them to the kind of person he’s going to run into on a train — he’s not going to find anybody, male or female — yet he keeps thinking he wants something transcendent expressed to him, but he can’t get it.” He sees a man on a train and follows him to a laundromat: “His chest was like Christ’s. That’s probably who he was.” He sees a woman behind a bar and looks into her future: “Your husband will beat you with an extension cord and the bus will pull away leaving you standing there in tears, but you were my mother.”

Within the book’s fallen world, everyone seems to have a dual identity. A farmhouse full of jocks turns out to be a drug den: “Football people. I didn’t know they ever got like that.” This applies to Fuckhead too. One moment he’s helping a stranger home, and the next he’s threatening to beat up a woman whose husband sold him bad drugs. It’s not simple drunken sentimentality that lets Fuckhead see light inside the worst people he encounters. Here he’s talking about Dundun, who’s just killed a man, who’s said he ought to work as a hit man, and who, we’re told, will torture another and beat a third nearly to death:

Will you believe me when I tell you there was kindness in his heart? His left hand didn’t know what his right hand was doing. It was only that certain important connections had been burned through. If I opened your head and ran a hot soldering iron around in your brain, I might turn you into someone like that.

Johnson pulls this zoom-out trick of having Fuckhead address the reader or the other characters across the years several times in Jesus’ Son, which he modeled on Isaac Babel’s “Red Cavalry” stories. The stylistic debt is obvious. Babel: “The orange sun is rolling across the sky like a severed head”; Johnson: “Under Midwestern clouds like great gray brains we left the superhighway.” Babel and Johnson were writing about casualties of different sorts, but a landscape of derangement fits both war and addiction. Under such circumstances, the pathetic fallacy — a character’s feelings being projected onto the world — becomes concrete reality. John Jeremiah Sullivan has pointed out that much of the prose in Jesus’ Son is indistinguishable from his poetry if you break up the lines. The book is also marked by a few radical technical decisions: no backstories, no transitions, spliced timelines, and jumbled tenses. These moves, which are also shortcuts out of psychology, have the paradoxical effect of both mimicking the addict’s consciousness and heightening the reader’s attention. The book provides the illusion of a clarifying delirium, like a good drug experience.

There’s one more element to the power of Jesus’ Son: sudden and singular images that emerge as if out of dreams or nightmares. These characterize all of Johnson’s fiction, but in this book they’re delivered at a high concentration. “Emergency,” the collection’s best story, is a litany of images: a patient who walks into an emergency room with a knife stabbed into his eye socket; a drug guru being interviewed at a county fair with eyeballs that “look like he bought them at a joke shop”; the eight baby rabbits Fuckhead’s friend Georgie cuts from the belly of an animal he runs over, later crushed to death when Fuckhead sits on them; the movie playing at a drive-in theater seen through a September blizzard (“Famous movie stars rode bicycles beside a river, laughing out of their gigantic, lovely mouths”). Elsewhere in the book there’s a baby lolling in the backseat of a car that’s just been wrecked, feeling its cheeks to see if they’re still there; a woman flying aloft tied to a kite pulled down the river by a speedboat; the scars on both cheeks of the hospital roommate Fuckhead shaves, marks of the bullet that passed through his head. You don’t soon forget these images, though you might forget that they all fill the same book.

There’s one more stark image: Fuckhead spies on a Mennonite woman in her townhouse as she showers and dines in the evening with her husband. There’s something about her purity and apartness that he can’t look away from, that he wants to run away with. He sees her husband wash her feet in what seems to be a gesture of apology. Would he be forgiven for being a peeping Tom? Fuckhead’s questing and his transgressing are still one and the same impulse.

Jesus’ Son got the IRS off Johnson’s back, gained him a cult following that eventually outgrew the term cult, and was adapted for the screen in 1999 with Johnson as the man who walks into the hospital with a knife in his eye. He lived between Idaho, Arizona, and Texas; had what was by all accounts a loving and steadying third marriage; and with his wife Cindy homeschooled their children.

He reported from Iraq, Afghanistan, Liberia, Somalia, and remote corners of the United States, reportage collected in Seek (2002). He wrote four plays.

The six works of fiction — five novels and a novella — that Johnson published between Jesus’ Son and his death are promiscuous in form and tone. One useful way to categorize them is as a set of opposing pairs. There are two long novels, Already Dead (1997) and Tree of Smoke (2007). The former is a violent and gothic (there’s a character called Frankenstein) descent into California’s drug culture; it’s creepy, funny, and bonkers in darkly satisfying ways, perhaps too strange to be justly appreciated as one of Johnson’s major works. The latter married Johnson’s lyrical style — at times as delirious as the prose in Angels, the novel included the Houston brothers among its large cast of characters — to big historical subject matter.

Two books are too self-consciously slight: The Name of the World (2000), the story of a widowed former Washington speechwriter’s encounter with a beguiling performance artist, an experience that sends him in flight from his staid life to report on the first Gulf War; and Nobody Move (2009), a comic noir in prose pared down to an unrecognizable minimalism. The historical novella Train Dreams (2011), a nominee for the Pulitzer that wasn’t awarded in 2012, and the thriller The Laughing Monsters (2014) are best considered — as the novelist Norman Rush, along with Sullivan, Johnson’s most incisive critic, have pointed out — Christian parables: One recounts, with the spareness of late Tolstoy and in the most refined prose of Johnson’s career, the life of an upstanding man in the Northwest of the early-20th century whose wife and child are taken from him by a forest fire “stronger than God”; the other, a hard-boiled and unsympathetic number, traces the unsavory doings of a pair of operators, selfish agents of foreign powers, in Africa, villains neither punished or redeemed.

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden is only Johnson’s second collection of stories, but it’s further proof that the form was his natural mode. The middle-aged man who narrates the magnificent title story lives in San Diego and works in advertising. We know enough about his life — college at Columbia, two years working for the New York Post, 13 years making television commercials on Madison Avenue — to know that if he had some Fuckhead-like lost years, he isn’t telling us. But his past isn’t squeaky-clean either, and memory is a zone of regret. He’s an impostor in the matrix of the American Dream. The bonds he’s formed are with people one way or another broken, or with healers, like his partner, Elaine. She does volunteer work, things like teaching adults how to read.

It’s Elaine who brings together the characters in the story’s opening scene, a dinner party. There’s a survivor of a coronary, a woman who became a grandmother at 37, the brother of a Tourette’s-syndrome case embarrassed at his sibling’s compulsion to shout about penises in public. The story’s focus settles on a veteran of the Afghanistan War whose leg was taken by a land mine on the outskirts of Kabul. A woman wants to see the amputee’s stump. The man agrees to remove his prosthesis if she kisses his scar. After some hesitation, she agrees, but, on her knees, with the half-missing limb two inches from her face, she starts to cry and the room goes quiet. The silence is broken by a man who boorishly mentions once seeing the amputee beat up a couple of men outside a bar. The narrator tells us this “ruined” the moment, but he also informs us that six months later the amputee and the woman he asked to kiss his stump were married.

In the same manner as “Emergency,” the story goes on accumulating its power with indelible images, some tragic, others comic to the point of absurdity. Life is equated with a masquerade, and the narrator acknowledges wearing a mask of his own, though one he’s worn so long it’s stopped being a disguise. Like many of Johnson’s narrators, this one is indifferent to our sympathies. Altogether, the story’s catalogue of moments from middle age constitute a preparation for death. Of his wife the narrator says, “Elaine: she’s petite, lithe, quite smart; short gray hair, no makeup. A good companion. At any moment — the very next second — she could be dead.” Of himself, a man whose most notable achievements are a few prime-time TV ads from decades back, he says: “I have more to remember than I have to look forward to. Memory fades, not much of the past stays, and I wouldn’t mind forgetting a lot more of it.”

The rest of The Largesse of the Sea Maiden splits neatly into halves, of young men and older men and their reckonings with death: the addict’s brushes with death, murders intentional and accidental committed by convicts, deaths of friends, stillborns, the ashes of 9/11. The wildest story in The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, “Doppelgänger, Poltergeist,” springs from an acquaintance of mutual admiration between the narrator, a writer teaching at Columbia, and Marcus Ahearn, a student with obvious poetic talent. Marcus also has a long-standing obsession with Elvis Presley that spins out into a supernatural conspiracy theory, involving miscarried twins (including Elvis’s own), grave robbing, reincarnation, murder, and the CIA. The Twin Towers fall halfway through the story, a whopper of an allegory for American paranoia.

The narrator of “Triumph Over the Grave,” who will spend much of the story looking after dying friends, gives this account of his calling:

Writing. It’s easy work. The equipment isn’t expensive, and you can pursue this occupation anywhere. You make your own hours, mess around the house in your pajamas, listening to jazz recordings and sipping coffee while another day makes its escape. You don’t have to be high-functioning, or even, for the most part, functioning at all. If I could drink liquor without being drunk all the time, I’d certainly drink enough to be drunk half the time, and production wouldn’t suffer. Bouts of poverty come along, anxiety, shocking debt, but nothing lasts forever. I’ve gone from rags to riches and back again, and more than once. Whatever happens to you, you put it on a page, work it into shape, cast it in a light. It’s not much different, really, from filming a parade of clouds across the sky and calling it a movie — although it has to be admitted that the clouds can descend, take you up, carry you to all kinds of places, some of them terrible, and you don’t get back where you came from for years and years.

This is a more easygoing vision of being a writer, terrible descents aside, than the one implied by the rules Johnson gave to his writing students:

Write naked. That means to write what you would never say.

Write in blood. As if ink is so precious you can’t waste it.

Write in exile, as if you are never going to get home again, and you have to call back every detail.

These are romantic bromides — a hard-core version of “Find your voice” and “Write what you know” — but they do imply elements of what made Johnson the lyrical Christian visionary we’ll be reading for a long time to come. His material was the stuff of the confessional and the AA meeting. His youth had taught him that life could be, would be, short. He lived in exile from that youth and transformed it into books that are the sort of redemption that never ends.

*This article appears in the January 8, 2018, issue of¬ÝNew York Magazine.¬Ý