There are many eyes trained right now on Studio Ponoc, the animation studio that rose from the ashes of Studio Ghibli following the latterÔÇÖs shuttering in 2015. Founded by When Marnie Was There director Hiromasa Yonebayashi and producer Yoshiaki Nishimura, itÔÇÖs a venture that couldnÔÇÖt help but be viewed as a spiritual continuation of Ghibli at best, and in GhibliÔÇÖs shadow at worst. Even the founders themselves, in a making-of documentary that aired in Japan, stated that their mission was to ÔÇ£make films that embody the spirit of Studio Ghibli.ÔÇØ But with general financial impracticality being the chief reason cited for the adored studio calling it quits, one had to wonder: What would Ponoc do differently that Ghibli hadnÔÇÖt been able to, in order to maintain both creative and financial solvency?

Mary and The WitchÔÇÖs Flower, the debut feature from the studio, goes a little ways toward answering that question while leaving plenty up in the air. YonebayashiÔÇÖs film is in many ways identifiably of Ghibli lineage. With its plucky preteen heroine, fantastical flying sequences, and boundless imagination for transformative physics, it seems welcoming at first, a tale to sink into like an old comfy chair. It gets there, eventually, but while Studio Ponoc gets its sea legs it also suffers from a kind of halting rhythm and visual flatness. ItÔÇÖs far from catastrophic, but itÔÇÖs enough to convince one never to take GhibliÔÇÖs fluidity and wonder for granted again.

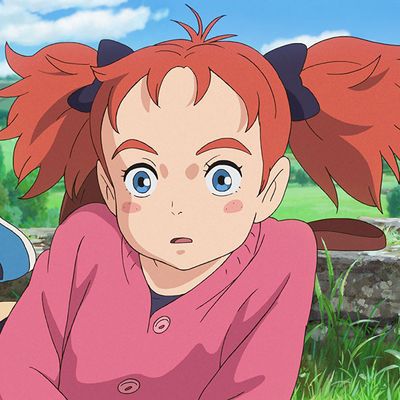

Yonebayashi, with his apparent affinity for semi-obscure British, female young-adult novelists, has found his source material in Mary StewartÔÇÖs The Little Broomstick, originally published in 1971, which exists both chronologically and conceptually between Alice in Wonderland and Harry Potter. The story concerns a lonely 10-year-old who discovers a broomstick in the woods, along with a magical flower, whose bluebell-like blooms can transform her into a powerful witch, one night at a time. On her first go-round, her broomstick goes on autopilot and takes her to an immense, floating witchÔÇÖs college in the clouds. MaryÔÇÖs preeminent gifts, along with her auspicious red hair, earn her special treatment from the headmistress and the mad professor Dr. D., and Mary is happy to soak it up.

But there are plenty of reasons to raise an eyebrow at the college, for both its founding principles and its filmic presentation, which is strangely stilted despite its multicolored fabulousness. During her first tour of the place, Mary (amiably voiced in the English dub by The BFGÔÇÖs Ruby Barnhill) keeps pinching herself, then ultimately decides to see out what must be a crazy dream, and we canÔÇÖt exactly blame her; thereÔÇÖs something kind of unreal and distant about Endor College. Yonebayashi chooses to frame a lot of establishing action in a medium-wide frame that has the feeling of a puppet show, thereÔÇÖs nothing kinetic or dazzling about MaryÔÇÖs or our discovery of this new world. So when Mary is revealed as an imposter and the darker side of the school and its faculty rears its head, it comes as less of a shock than perhaps it should.

But what Mary lacks in the resources to visually gobsmack, it partially makes up for with its unstoppable titular ginger, whose empathy, depressive streak, and enviably fierce eyebrows place her shoulder to shoulder with any Ghibli heroine. Much of the filmÔÇÖs arc depends on MaryÔÇÖs inner emotional life, her solitude, and her desperate desire to be good at something. The temptations of witchery, and her temporarily elevated status at Endor, are almost narcotically seductive to her. Hilariously, then, the film can almost be read as a one-to-one anti-drug parable, with the superpowers of the flower (they make her popular and good at everything, keep her out late at night and wear off within 12 hours) being a crutch that Mary must inevitably learn to do without.

Unfortunately, the film is stuffed with so many other less-coherent ideas, including a genetic-engineering plot that gestures toward real-world corollaries but never completes the sentence. At different points the headmistress states that ÔÇ£electricity is a kind of magicÔÇØ and ÔÇ£potions are nothing but chemistry,ÔÇØ proclamations that seem written to elicit an mind-blown reaction GIF but kind of fall apart as soon as you start thinking about them. A revelation near the filmÔÇÖs climax about a certain characterÔÇÖs identity is somehow both predictable and nonsensical, and doesnÔÇÖt really pay off aside from its immediate convenience to the plot.

More concerning is how much of the visual elements feel remedial. The shape-shifting, dolphin-like fighter planes that swarm a mystery heroine in the filmÔÇÖs prologue are bracing at first, until one realizes they are almost lifted whole cloth from YonebayashiÔÇÖs work on Hayao MiyazakiÔÇÖs Ponyo. The floating, palatial Endor College and its staff of robot guards is reminiscent of another castle in the sky. At one point a villain conjures a huge, sticky black arm in an attempt to apprehend our heroine, and it resembles both an iconic monster from Princess Mononoke and Studio PonocÔÇÖs biggest challenge ahead: to always stay one step ahead of its predecessorÔÇÖs legacy. But if Mary and the WitchÔÇÖs Flower tells us anything, it is that such things are possible: When Mary can no longer depend on the flowerÔÇÖs magic, she has to dig deeper into her own reserve of character to complete her mission. And IÔÇÖll admit that by that point, despite whatever creaks and lags had preceded it, I felt a compulsive urge to see it through and follow Mary and her little barking broomstick wherever they went.