In what’s threatening to become the next “Blurred Lines,” there’s a new hotly contested copyright dispute brewing that involves two powerful names in music, as well as one of the defining songs of the ’90s. Lana Del Rey revealed last weekend that Radiohead is suing her over similarities between her Lust for Life album closer “Get Free” and the band’s most-known hit, “Creep.” In her tweet, she accused Radiohead of coming after an astounding 100 percent of the song’s publishing rights after she said she had offered 40 percent, saying “their lawyers have been relentless,” with the possibility that the song could be removed from future physical copies of the album. Her response: “We will deal with it in court.”

Though Radiohead has yet to publicly strike back, their publisher Warner/Chappell issued a statement to Vulture on Radiohead’s behalf days later shooting down much of Del Rey’s claims. Though they confirmed copyright negotiations between the two camps have been ongoing since last August, they denied ever filing a formal lawsuit against Del Rey — implying that this was intended to be settled out of court — or that Radiohead had said they would accept nothing less than 100 percent of the song’s publishing.

With each party now telling opposing sides of the same story, it’s difficult to make heads or tails of what’s really at stake, if there’s legitimate fault, who’s bluffing here, and how such an infringement claim might play out in court. We spoke to Jeff Peretz, a copyright expert and professor at NYU’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, and Dan Bogosian, a musicologist, to find out if Radiohead might actually have a case and what’s fairly deserved if they do.

What is this dispute really about?

According to Radiohead’s publisher, the problem stems from what they believe is an obvious overlap between “Get Free” and “Creep,” to the extent that Lana’s song infringes on Radiohead’s copyright to “Creep.” This is their specific gripe and what they feel Radiohead is owed: “It’s clear that the verses of ‘Get Free’ use musical elements found in the verses of ‘Creep’ and we’ve requested that this be acknowledged in favour of all writers of ‘Creep,’” a spokesperson for Radiohead’s publisher says. Reps for Radiohead would not comment on who flagged the issue and initiated the complaint — Radiohead, or their publisher — but it’s now game on.

Are there actual similar “musical elements”?

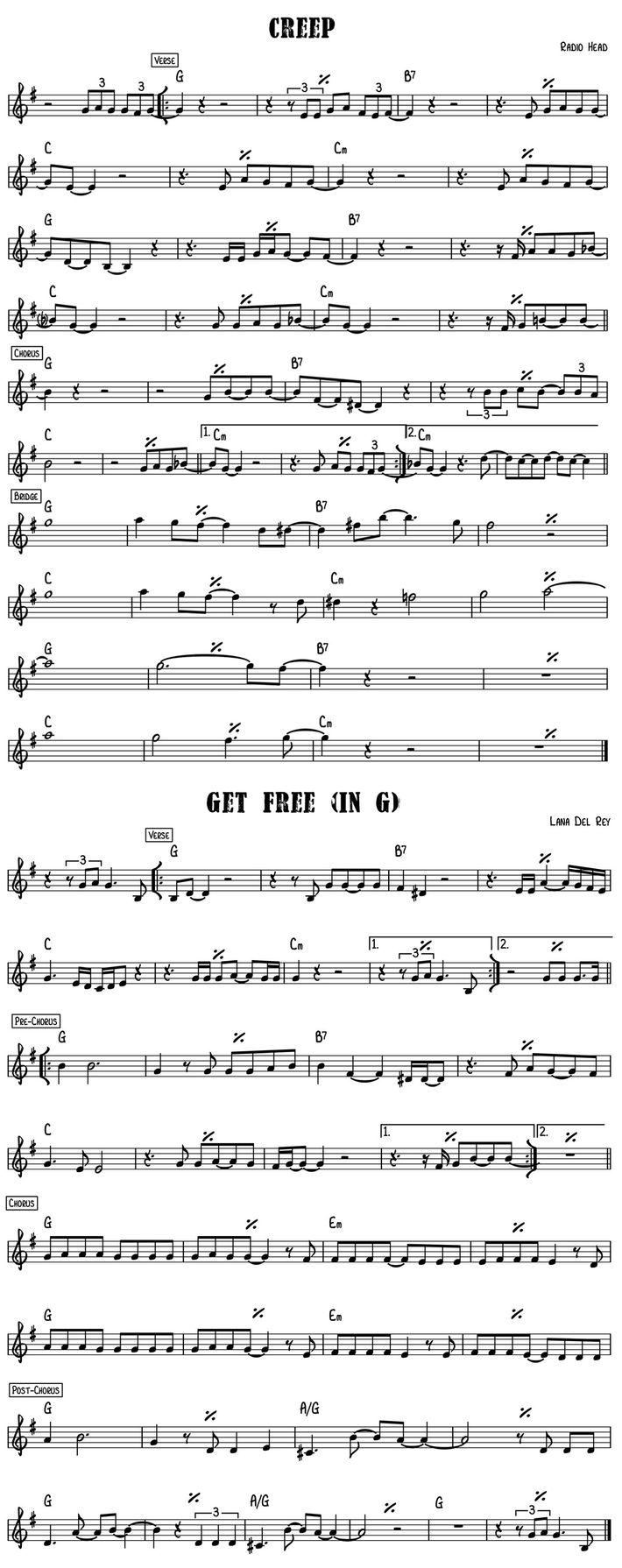

There’s no way of knowing what Radiohead’s publisher means by “musical elements” unless they elaborate in public records, but Bogosian considers it to denote melody. Though Bogosian believes the verses of “Get Free” obviously crib the instantly recognizable chord progression from “Creep,” it’s a famous one written as I-III-IV-iv, and duplicated chord progressions are so common in music that they can’t be copyrighted. (He points to Sam Smith’s “Midnight Train” as another example of being just one chord off from“Creep.”) Neither can rhythm, which he agrees also bites “Creep.” The fault as it pertains to copyright law is melody, which is where Bogosian notices Del Rey gets in trouble.

“Get Free” is written in the key of B-flat and “Creep” is written in the key of G — a minor third, or three half-steps apart, he explains — which makes their mathematical starting point slightly different. But, on paper, almost all of their intervals are the same. “If you wrote a jazz lead sheet [written for melody] and put them in the same key, those sections would be almost identical,” he explains. “And the melody is what most people consider to be the song.” That melodic structure coupled with the similar-sounding chord progression and rhythm bring the resemblance even closer. “The entire verse is just Lana doing her lyrics over Radiohead’s ‘Creep.’ She holds the same notes as Thom Yorke for the same duration at the same points and it’s the same relative pitches,” he says. “The guitar part is played to a different rhythm, but if you boiled it to the same key, the actual fingering and notes the guitar is playing would be the same.”

So, did Del Rey steal from “Creep”?

Bogosian puts it this way: “She Lana Del Rey’d it up. But the verses of ‘Get Free’ sound more like Radiohead’s ‘Creep’ than Prince’s cover of ‘Creep.’ Prince plays it twice as fast and the melody is not the same song at all. The lyrics are. But Lana Del Rey took ‘Creep.’ If you tried to do a ’90s cover of ‘Get Free’ it would be ‘Creep.’”

Does it matter if it was a coincidence?

Though Del Rey maintains she was not inspired by “Creep,” according to Peretz, intent does not factor into copyright law. It dates back to a lawsuit involving George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” and the Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine,” which ended with Harrison found guilty of “subconsciously” stealing from the song though he hadn’t heard it at the time of writing. A more recent example of that ripple effect is Sam Smith agreeing to share royalties and songwriting credit with Tom Petty on “Stay With Me” when it appeared that song stole from “Won’t Back Down,” despite Smith claiming it wasn’t an influence. “That’s the danger of this litigious behavior. It doesn’t matter if she intended to plagiarize or not,” Peretz says. “It’s just: Did she land on the same notes on the same chords? At times, she does. And if we’re defining that as copyright infringement, which we are, and she is now owing to put them on the copyright, then that’s what’s going to happen.” He adds, “As random as the whole thing is, the notes she chose on those particular chords resonate in a certain way. That’s what ‘Creep’ sounds like and that’s why this whole thing has happened.”

Who are “all” the writers of “Creep”?

Ironically, Radiohead was sued for copyright infringement on “Creep” when the Hollies claimed that it stole from their 1974 song “The Air I Breathe.” Songwriters Albert Hammond and Mike Hazelwood later received an undisclosed percentage of the publishing rights and royalties in an out-of-court settlement, and are credited as co-writers on the song to this day. Peretz believes that when Hammond and Hazelwood became co-publishers of “Creep,” there was likely a clause in the settlement stating that any future legal dealings regarding “Creep” would include them. He imagines both Hammond and the estate of Hazelwood, who died in 2001, would likely be onboard with the Del Rey dispute, as they stand to financially gain from it should Radiohead, Hammond, and Hazelwood get shared credit on “Get Free.” Radiohead’s publisher’s statement indicates that that’s the desired outcome.

How rare is to ask for 100 percent of the publishing?

Bottom line: very. “That sounds like made-up bullshit,” Peretz says. “They can’t demand 100 percent ownership of a song they didn’t write.” Though rare, there is precedent: In 1997, the Rolling Stones’ manager Allen Klein sued the Verve over a “symphonic version” of “The Last Time” sampled in “Bittersweet Symphony.” While the Verve had agreed to offer 50 percent of the royalties to license five notes of that version, Klein claimed they used more than what was agreed, therefore voiding the contract and leading to the lawsuit. In the end, the Verve were forced to forfeit 100 percent of the royalties and publishing to Mick Jagger and Keith Richards; to this day, the Verve never see a dime from their own hit and have no control over its use.

“Whether you want to say they took the music for ‘Bittersweet Symphony’ or not, they wrote the lyrics,” Bogosian says. “You think they’d get half. But no, for whatever reason, the jury or judge rewarded 100 percent to the Rolling Stones.” He adds, “Maybe that’s why Radiohead or their publisher want to litigate.” Peretz questions the validity of Del Rey’s 100 percent claim, given how historically rare it has been for a musician to demand that much leverage over their peer’s work, suggesting that there may have been some smoke and mirrors in her tweet as a strategy to negotiate the percentage down in future settlement talks. He notes, “One-hundred percent? I can’t imagine a jury would ever say, ’This song is now owned by Radiohead.”

Do Radiohead deserve 100 percent?

Not a chance. According to Peretz, because there are three sections to each of the songs, but only one of them (the verses on “Get Free”) has similarities to “Creep,” Radiohead should only be rewarded by that one-third math. “Even if this went to court and there was found to be some sort of an infringement, there’d be a settlement and Radiohead would be added to the copyright,” he says. “But they would never own the song outright 100 percent.” By Bogosian’s educated guess, roughly 60 percent of “Get Free” is Lana’s original work. For that reason, he finds her claim of having offered 40 percent of the publishing rights an accurate and fair amount. “If I were the judge, jury, or called to court as a musicologist, I would literally time the verses of the songs and then give Radiohead that percentage over the whole song,” he says. “I don’t want to see Lana destroyed over something so stupid when she did clearly write other parts of the song.”

What makes this different from the “Blurred Lines” case?

Much of the “Blurred Lines” lawsuit, in which a jury determined that Robin Thicke and Pharrell stole from Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up,” boiled down to copying what was described as the “vibe” or “feel” of Gaye’s original. With Lana and Radiohead, it’s a reverse situation where the sonic “vibe” of each song doesn’t match but the math does. “‘Blurred Lines’ had almost nothing in common with Marvin Gaye’s song, in terms of music theory. Everything about it in an ethereal sense pointed to Gaye, but everything in a literal, conceptual sense didn’t. [Pharrell] put enough spin on it so that there were no scientific similarities,” Bogosian explains. “But you wouldn’t listen to ‘Get Free’ and think Lana stole the production techniques of Radiohead because it doesn’t sound like a Pablo Honey song. But then in a music theory sense, it’s as similar as you can get.”

Why do Radiohead even care about “Get Free”?

Bogosian and Peretz both agree that Radiohead taking umbrage with “Get Free” is curious, given that the song is a little-heard deep cut that closes her last album and hasn’t been released as a single. Most copyright cases involve hit songs raking in millions, like “Blurred Lines” and “Uptown Funk,” so why this particular hill to die on? Peretz speculates that Del Rey preemptively publicizing the news prior to Radiohead’s filing might have tactfully pointed out that very inconsistency while also using it to her advantage: “That may be a reason why Lana’s camp would put out this information that Radiohead are asking for 100 percent. It’s almost hyperbolic to come out with that kind of a statement. It promotes the song.” He adds that the dispute will ultimately be a win for both sides, regardless of the outcome. “In hindsight, this is going to turn out to be a brilliant move. Everybody’s talking about it and streaming these songs.”

What’s the next step?

Because each party appears to want different things — Radiohead seemed fine with private negotiations, while Del Rey now wants to leave it up to the courts — it’s difficult to know if this dispute will head to litigation and a full-on trial. For the sake of camaraderie in music, Peretz hopes it doesn’t come to that. “I don’t think either of these artists stand to benefit from this thing winding up in a court of law. Right now they’re putting words in each other’s mouth that doesn’t make much sense,” he says. “Eventually we’ll see a settlement and I think they’ll find a way to meet in the middle.”

The very news of the case, regardless of whether it leads to any repercussions, could add to the growing industrywide confusion post–“Blurred Lines” over how to navigate creative similarities that fall in gray areas, and even those that are less ambiguous. “Worst-case scenario: We end up with some kind of ‘Blurred Lines’ bullshit where they award a ridiculous amount of money for a song that never even really made that much money,” Peretz says. “There’s always the question: What’s thievery and what’s homage? What’s borrowing and what’s influence? There are all these ways that music can be ‘copied.’”