When Cary Fukunaga tapped her to create the 1896 New York City of The Alienist, production designer Mara LePere-Schloop was no stranger to combining character-driven set pieces with a moody, palpable sense of place. As Fukunaga’s art director on the first season of True Detective, she was responsible for imbuing the production with its gothic, fecund, deep-South vibe — and M. Night Shyamalan, impressed by her work, tapped her for the challenging job of weaving subtle nods to 27 separate personalities into the underground lair of the villain in Split.

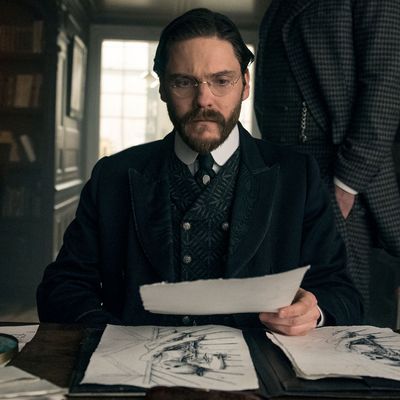

But The Alienist, TNT’s astronomically expensive adaptation of Caleb Carr’s eponymous novel, was something new. Centering on a series of grisly murders, the show follows criminal psychologist Laszlo Kreizler (Daniel Brühl) and New York Times illustrator John Moore (Luke Evans) as they discover dismembered corpses all over the island of Manhattan — which is a character in and of itself, and a pivotal one.

“Not only do you have the characters of the story, showing day-to-day life in the city of that time, but you have these crime scenes in still existing locations. The stakes are high to try to get things accurate,” LePere-Schloop says of the series, which premiered on January 22. “There was a three-week period when Cary first called me, where I went down the black hole of research.”

The production designer dug through photo archives, books, and ancient construction blueprints to create the New York seen onscreen — but still had to cross the Atlantic to find a city that could stand in for the Big Apple. Speaking with Vulture from her home in New Orleans, LePere-Schloop walked us through the challenges and highs of bringing the city to life.

Budapest for New York

For a show so thoroughly rooted in the history of New York City, The Alienist has a surprising secret: Not a single scene was filmed in the U.S., though not for lack of trying. LePere-Schloop spent four months trying to work out the logistics of producing the show in New York, but much like the crew of The Knick, found that period-appropriate settings were few and far between.

“We kept having to shrink our ambitions,” she said. “But just when we thought the show was going to die a sad death because we couldn’t figure out how to produce it, someone said, ‘Have you thought of Budapest?’”

The suggestion turned out to be a stroke of genius: “Suddenly all these things that were proving difficult, if not impossible, to get in New York — a Met Opera, a Delmonico’s, all these really decadent Gilded Age interiors — in Budapest, we were given these options that were incredible, and where we had control for long periods of time.” The interior landscape of the original Delmonico’s is lost to history, but several rooms in the gorgeous Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library had the right look and feel — and made a perfect backdrop for an authentic 1896 dinner that takes place in the second episode. Prop master Ellen Freund used the restaurant’s book Dining at Delmonico’s as a reference, creating an elaborate three-course meal that was “historically accurate and also edible.”

For the show’s street scenes, however, a massive set had to be created — ten city blocks, built from scratch. “The cobblestones in the streets, every sign in every window, every drape,” LePere-Schloop said. “Every single detail, we made.”

A City of Character

LePere-Schloop created two look books for the production of The Alienist. One was a catalogue of the eye-catching historical details of 1890s New York, from a pastoral Central Park where wealthy children rode in carriages pulled by goats to the Lower East Side where less-fortunate children had to play in streets littered with garbage and the occasional horse corpse.

“The unspoken hurdle of trying to produce The Alienist is that so much of the character of the novel is Caleb’s descriptions of the city at that time. The high to the low, going from the opulence of the Gilded Age to the tenements,” said the production designer. But in addition to telling the story of the city, the sets — almost all of which were built from scratch — had to convey a lifetime of backstory for the characters who lived in them. “You don’t want to just build these massive things and have them feel empty. The character development, that’s their personal habitat.”

LePere-Schloop’s favorite set is Kreizler’s home, a richly textured sanctuary for the passionate, eccentric doctor that reflects his fondness for luxury as much as his dedication to his work. Keep an eye out for the detail and craftsmanship in each room of Kreizler’s mansion — particularly the huge stained-glass window on the second floor, which was a massive labor of love: “We spent three months making real stained glass, with real lead. Every color was hand-chosen.”

The Pisspot Police

Although commissioner Theodore Roosevelt ruled the police department at the time of The Alienist, the show’s police station was built around another character: Sarah Howard (Dakota Fanning), the department’s first female employee. “The design of the police station very much stemmed from Sarah’s experience walking through the station,” LePere-Schloop explained. “As she gets to her office it becomes narrow and more confined. I wanted it to be an oppressive journey. She has to walk through the equivalent of a boys’ locker room to get to her office.”

And because indoor plumbing was a rare luxury in the New York of 1896, that locker-room analogy is uncomfortably apt; in one scene, Sarah opens and then hastily shuts a door to a room where one of her colleagues is relieving himself into an authentic, turn-of-the-century pisspot.

“They’re all over the police station; if you keep your eyes peeled you’ll see them,” said the production designer, who estimated that the production required upwards of 30 pisspots (or “things repurposed as pisspots” — not all of the vessels seen onscreen are strictly regulation pee receptacles). But the ubiquity of the containers serves a dual purpose: In addition to historical accuracy, they provide important feminist context. “That’s another thing we wanted to show,” LePere-Schloop said. “The only women you see in the police station are cleaning up after the men. You think about these women, having to clean those things out and empty them during the day.”

The Boy on the Bridge

The debut episode of The Alienist centers on a stunner of a scene, in which the mutilated body of a boy prostitute is found sprawled in the snow atop the Williamsburg Bridge. Creating the set was a challenge from the start; in 1896, the bridge was just barely under construction, and documentation of the process was sparse.

“We were able to find the original construction drawings, and just enough photographs to kind of piece it together,” said LePere-Schloop. To really convey the precarious nature of being up on the unfinished structure in the middle of the night — and Moore’s harrowing ascent to the body’s location — LePere-Schloop built the set at a height of 50 feet, about one-third the height of the real-life structure, but more than high enough to produce the desired effect: “You would get wind, you’d get these organic conditions, you have real night sky to shoot against. If you were on a soundstage you’d have to blue screen every detail,” she explained. But on the actual elevated catwalks of their bridge, LePere-Schloop said, “You could hear it, you could feel it. We built it so that there was some sway.”

Onscreen, the result is striking. The set shudders, groans, and creaks, and Luke Evans in particular looks like he’s right on the brink of barfing — no acting required.

“It was one of those things where the actors both cursed me and thanked me for it being raised,” LePere-Schloop said, laughing. “I’m pretty sure Luke is afraid of heights. The first time we had a rehearsal up there, there were a lot of four-letter words coming through the mic.”